Avantika Bawa

My first meeting with Carrie Gundersdorf was at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, where we were graduate students in the Painting and Drawing department. I have followed her work closely since then. Of special interest to me are the back and forth shifts in her practice from ‘painterly painting’ to quirky collages, and more recently obsessive, labor-intensive color pencil drawings. A lot of this stems, I believe, from her fascination with astronomy and science, and an unrelenting, and somewhat bratty, desire to redefine our interpretation of their visual representations, all while looking at the history of Modernism.

All works by and courtesy of Carrie Gundersdorf unless specified.

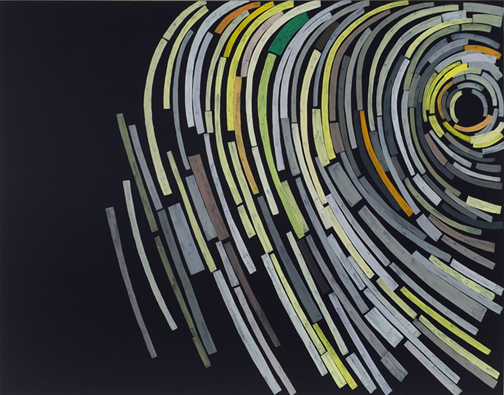

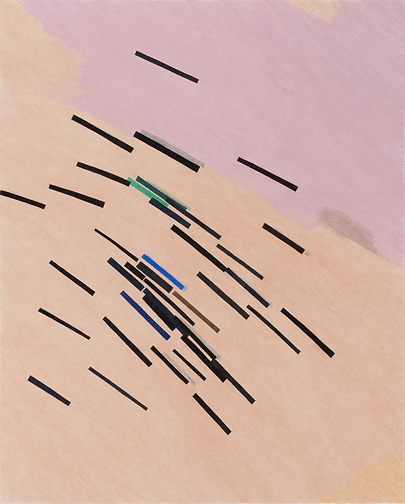

Southeast Trails – with fish-eye lens – 4.5 hours, 2007, o/c, 55″ x 70″

Avantika Bawa – How and when did your interest in star gazing and astronomy start?

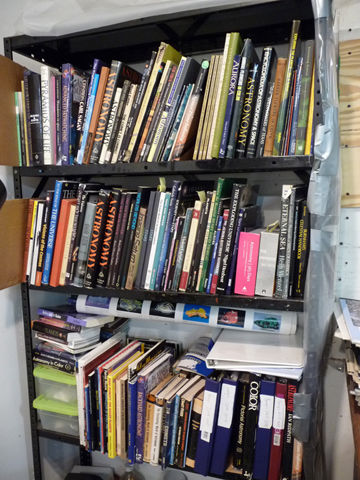

Carrie Gundersdorf – Growing up, I was really interested in astronomy and star-gazing. It was one of many interests that involved nature, collecting, and being outside. I grew up in a small town in Maine, and, we, the kids in the neighborhood, were outside all of the time. It was the country, barely any traffic and lots to explore. My Dad and I went rock hounding; we went to old quarries to look for rocks and minerals, and we would also spend time outside looking at the sky with my telescope. There were no street lamps, so the night sky was big. Nature in general felt big, full of stuff to discover. (I guess I was a pretty nerdy kid, and, of course, a lot of this lost its appeal after I became a teenager). This interest in astronomy manifests itself in a different way now. I spend time finding astronomy and other science/nature books at used bookstores and flea markets, and finding images online. I live in a large city, and I don’t have a telescope; instead I have hundreds of collected books and images in my studio, and this collecting is a generative part of my process. In the work, I am interested in the idea of discovery and natural phenomena and how these are found through images and then translated through painting or drawing.

Gundersdorf Studio, 2010

A.B – You earned a Bachelor’s degree in Liberal Arts, before moving on to a more specialized education in Fine Arts, through your time spent at the Maryland Institute College of Art and later at the School of The Art Institute of Chicago. I think I see this kind of approach in your work as well. You begin the work or rather ‘converse with’ the concepts embedded in the work, through a genuine curiosity for science, nature, and the power of observation. You seem to gather practical information from all kinds of sources—books, walks, travels, mass media etc. Then you proceed to make the ‘work’. Eventually this catalyst seems secondary, and the work is more about the language of art, than it is about the understanding of science. Would you agree?

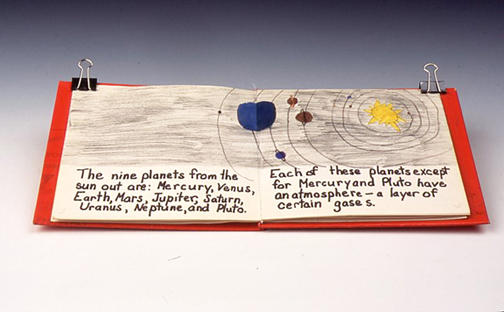

C.G – I think you summed it up well, but the process is always a little messier in reality. When I left graduate school, I was making large paintings that played with an optical effect with color relationships and background/foreground space. I was also interested in instilling a sense of the homemade/the hand into these formal paintings. I made several paintings and reached a point where the paintings felt like a known entity before starting them. At the same time, I started collecting astronomy/nature photos and books—I wasn’t quite sure what I was going to do with these. I also found a pop-up book about astronomy that I made when I was about 9 or 10 years old which evoked a sense of wonder that I was interested in having in my work. It took some time to figure out how and what to do with these images and how to integrate observation into my process. At first, this seemed wrong—after graduate school, I had a specific idea of what an “Abstract Painter” should be. I had to break down some of my ideas, to open up my work.

Let’s Look at Space, Handmade book, c. 1985

So back to your question, I approach the collected images, books, and findings with my experiences and interests as an artist. And I take the images and extract compositional moments, colors, movements, employing modes of observation and abstraction—but through the languages of painting and drawing. The image is a jumping off place for me to think about themes of wonder and discovery. The back and forth between image and material, science and the handmade are ways to keep the work in a questioning space.

Found Star Trail Image

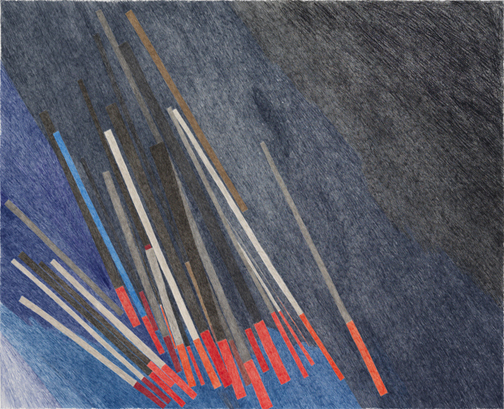

Horizontal Redshift Composition, 2010, colored pencil and watercolor on paper, 38″ x 46 ½”

A.B – And it is this moment that really draws me to your work. You’ve talked about the role of the initial source materials in your thinking, could you now talk a little more about your physical process in the studio?

C.G – My process is a constant negotiation between painting and drawing (and now collage also) and abstraction and observation. At any given moment, I usually have two bodies (or more) of work going on in my studio. These projects often vary in speed (with labor), material, and/or their relationship to source material. Moving back and forth between drawing/painting and observation/abstraction has become a very generative process of working for me.

We often think of color as being associated with painting and line with drawing. My paintings are made much faster than my drawings, and I want to bring a sense of drawing into the mark-making. I use small brushes almost exclusively for the foreground, more akin to drawing. I hope that this embeds a sense of modesty in the work and that the viewer can see the process of the painting being made. The large colored pencil drawings have a coat of watercolor underneath, an under-painting; they are labor intensive and are made by building up color (via colored pencil). I am interested in the distinction between my looking at the photo and making the work, and a viewer looking at the piece.

Trails and Space, light flesh version, 2009, colored pencil and wc/paper, 49″ x 40″

A.B – Although varied, your choice of materials and color seems very deliberate. I’ve seen you work magic with Liquin, Williamsburg paints, archival paper etc on one hand and also Crayola and construction paper on the other. Are these choices in the hierarchy (lowbrow vs. highbrow) of material purely formal?

C.G – The material choices are important formally and content-wise. Thinking about the history of modernism, I purposely want to instill a sense of the homemade in my geometric paintings and hope there is something a little off in the composition. And the use of colored pencil and crayons are both formally interesting and evoke the spirit of discovery. The drawing titled Diagonal Composition with Laser Lemon, 2010 sums up the combination of a possible modernist title with a great Crayola crayon color.

Diagonal Composition with Laser Lemon, 2010, crayon, charcoal, colored pencil and wc on paper, 44 1/2″ x 60″

A.B – What you said about modesty and discovery in your works is so true. I am particularly intrigued by how you offset this thinking with the bold scale (and color) of some of your works. In the larger pieces, the work literally jumps at you, while still retaining a sense of innocence, often due to the material and marks used.

C.G – Thanks, I hope that is what comes across! I think the larger paintings are about body size, so they are not too large. Also, I often try to create a specific relationship with the viewer by hanging the pieces lower than normal. I hope the color relationships create a slow buzz rather than a loud noise.

A.B – Let’s talk a little bit about Supernature, the theme for this issue of Drain. I am interested in the way images of star trails, night skies, and so on from science magazines and postcards, among other things, are re-mediated in your art. Often you flatten the picture plane, simplify the images, and in a sense animate the expansive fields, hence altering their ‘Aura’. You extract the ‘Supernatural’ quality and make them less ethereal. So my question is, are you conscious of the Supernatural quality of these images and how you are addressing or toying with it in your works?

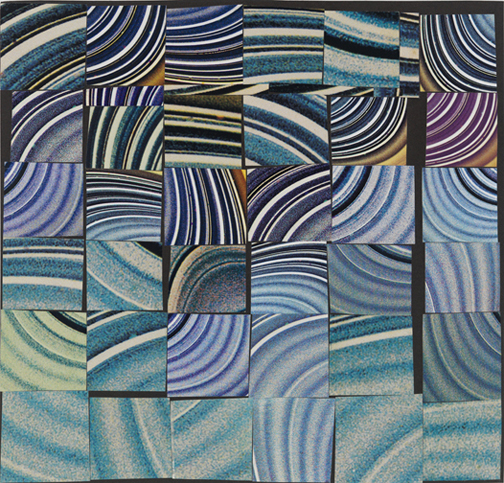

C.G – I love that word, Supernature…nature as superhero! I think what you are referring to with the word ‘Supernatural’ here is what cannot be seen with the naked eye in the photos. This is usually a time element that can only be captured by the camera, or an image with super-imposed color to describe specific information. For example, Two Widths of the Epsilon Ring (the painting and drawing versions) come from a photograph where orange is superimposed on an image of two sections of the epsilon ring around Uranus; the orange/yellow helps to describe where there is less matter and more light coming through the ring. I am interested in these moments that are beyond our vision, an abstraction in a sense, images that are attempting to know more about the universe.

There is a romantic-ness in the found photos and with the whole idea of looking at the sky. I am not trying to re-create that romantic element—I live in a city; my studio is in a basement; it is not a part of my everyday life to see stars at night. I am interested in creating a painting/drawing language about the idea of ‘aiming for the stars’ while showing the limitations of this goal. Ultimately, I think knowledge has to have a personal element to it, which is summed up well by Heisenberg’s ideas about “Ungenauigkeit,” (imprecision) and his statement about The Uncertainty Principle: that “the observer becomes a part of the system being observed.”

Two Widths of the Epsilon Ring, 2006, o/c, 60″ x 55″”

Actually, it’s interesting…I think you do this also with your work and architecture. Your work looks at specific architecture and its history and reacts to it, but in a quirky, personally charged way. Maybe this will be our next discussion.

A.B – Do you have any specific habits/rituals, or systems of organization in the studio? What do you listen to while working or is silence preferred?

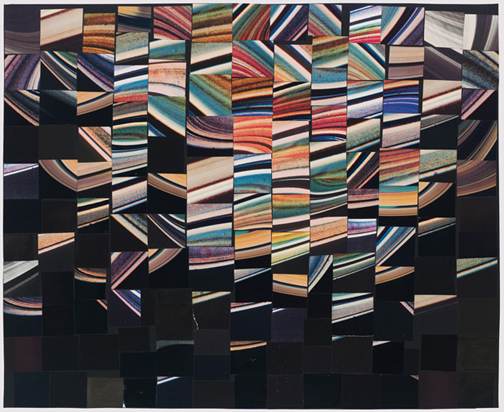

C.G – Hmm… a few are: When I am stuck or need time to get into my work, I go through books, cut out photos and organize them by image into folders. For example I have folders on nebulae, the sun with flares, the sun’s photosphere, Saturn’s rings, black paper, etc.—very nerdy! As for listening, I can only really listen to music, specifically whole albums. I find radio and books on tape to be too distracting.

Saturn’s Rings, 2009, found images/paper, 22 1/2″ x 27″

Saturn’s Rings Composition (blue), 2010, found images on paper, 9 1/2″ x 10″

A.B – What’s in the near future for you?

C.G – Well, I am making new bodies of work right now—a body of paintings and drawings that have a relationship to my collage work, and a series of drawings of nebulae. These are evolving, and I have not shown either yet. I also have been toying with an idea for a while to make a book. In addition, I am working to curate a show based on the Uncertainty Principle, which will be mounted in 2013. I am excited about this opportunity to think through some of these ideas in a conversation with other art work.

Eskimo Nebula, 2011, colored pencil/ paper, 10″ x 10” “

Carrie Gundersdorf lives and works in Chicago, IL. Gundersdorf’s solo exhibitions include the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, IL (2010); Julius Caesar, Chicago, IL (2010), Shane Campbell Gallery, Chicago, IL (2007), and Gahlberg Gallery, College of Dupage, Glen Ellyn, IL (2003). She has been included in group shows at Loyola Museum of Art; the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago; Regina Rex, Brooklyn; Marc Foxx Gallery, Los Angeles; Gallery 400, University of Illinois, Chicago; Hyde Park Art Center; Tony Wight Gallery; and SWINGR, Vienna, Austria, among others. Her work has been reviewed in Art Review, Chicago Tribune, Artforum.com, Artnet, Bad at Sports, Art on Paper, and Time Out Chicago.Gundersdorf is the recipient of the Artadia Award (2002) and the Bingham Fellowship (2000) to attend Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture. She received her BA from Connecticut College, New London, CT and MFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. carriegundersdorf.com.

Avantika Bawa is an artist living in Portland, OR and New Delhi, India. She Art Editor and co-founder of Drain.