SPURSE

Nearly twenty years ago we in SPURSE first sensed that many of us involved in the arts were reconceptualizing art in a way that was very different. It was not the usual debate about expanding the definitions of art (art into life and so on); it was, ironically, the opposite: artists wishing to limit the expanding definition of art. Artists wishing to be done with art. There was an urgency to step outside of art, not for the sake of shifting art into an alliance with another existing discipline, but for the sake of scrapping the existing realm of the aesthetic. What was being reconsidered was not solely art (as if it could still be thought of as a standalone endeavor) but also the entire project of Western metaphysics and all its neat dualisms: Nature + Culture, Subject + Object, Human + Non-Human, Fact + Value, Art + Science, and so forth. The pressing and unavoidable question that seemed to be on all of our minds was: If these interwoven logics, in which art plays a critical role, are no longer justifiable, then are the procedures that comprise art worth adhering to even as everything else is being critically rethought? Can we really be “after Nature” and “after Culture” but not “after Art”? Giving art a free pass no longer seemed viable or interesting. To be clear, this was not a continuation of the Post-Modern desire to critique all metaphysics and then ultimately be done with metaphysics. Rather, what we could sense emerging was an experimental curiosity to begin an adventure to co-evolve a new metaphysics after art.

We would like to put our cards on the table and say upfront that this essay is an attempt to change your attitude toward art and aesthetics. In reading this essay, We would love for it to spur you to participate—even if ever so briefly—in an adventure: to experimentally put aside and come “after art” so that we could speculate, if only for a brief moment, on what new ways of feeling, sensing, entangling, and being-of-a-world might emerge. While this goal might sound arrogant, presumptuous, and even absurd, we would be happy to simply give you an itch: if the costs and consequences of engaging the world in a way that contains the methodologies of “Culture” and “Art” are simply too high, then do we really need to continue operating in terms of Art (or Nature or Culture)? What new possibilities open up for aesthetics if we transform this larger mode such that art as a fundamental methodology no longer has a place?

Coming after is by no means an ironic claim. We would like to consider the possibility: be done with art. Stop. End. Walk on differently.

Nietzsche said it best: We have lost the ability to defecate. Here, we see this ability return. It is something to celebrate and think about. But what are we trying to digest and defecate? What is art? What we would like to digest and pass is the broad general conceptual schema that art is one small part of.

- What do you mean by general, implicit conceptual schemata?

Well, the regularities of our life have a historical consistency that speaks of a set of dynamic relations, implicit operational rules, and common structuring principles. I am interested in transforming these. McLuhan insightfully drew our attention to this, calling it our medium or environment, explaining, “Environments are not passive wrappings, but are, rather, active processes which are invisible.” And earlier in the work, he asserts:

All media work us over completely. They are so pervasive in their personal, political, economic, aesthetic, psychological, moral, ethical, and social consequences that they leave no part of us untouched, unaffected, unaltered. The medium is the massage. Any understanding of social or cultural change is impossible without a knowledge of the way media work as environments.[1]

Although there are many ways to define this concept, I think it is most usefully termed the contemporary Western mode of being-of-a-world. (For the sake of brevity, I will most often shorten this to “our mode of being,” or some derivative of this term).[2]

- How can one come “after art”? Isn’t art is simply part of being human. This all sounds a little too polemical—what does it mean to come “after art”?

I understand that we have heard it all before—proclamations about the death of all things: painting, art,[3] rain forests, childhood, and so on. Thus, we are duly cautious in facing what may seem like yet another instance of a decidedly reactionary form of crisis thinking. I am not out to kill painting, or art, This argument is not about “the end of art” (obviously art will end when it does—it is far beyond my abilities to assume the mantle of the futurist). Coming “after art” is a categorically different concept. Perhaps it would be better to phrase the endeavor this way: after X, art will occupy a very different place in the ecology of our meaning-making practices.

Here’s an analogy that—although admittedly a bit unfair—nevertheless has the advantage of making the point clearly: the horse-drawn buggy continued to be used after the invention of the internal combustion engine—it just operated in a very different manner in a very different ecosystem of transportation. The car, while evolving from the buggy, did not simply replace the buggy as the primary means of transportation; it radically transformed society in the process, such that today the buggy has been assigned a very marginal role in a totally distinct paradigm of transportation. My curiosity is about what happens to art after such a paradigmatic transformation (of our Western mode of being-of-a-world).

- Is this simply more academic navel gazing? What is the real urgency for this move beyond the category/institution of art?

It could be; such exercises most often are. This essay is a call to stop the navel gazing, to take the consequences of our implicit actions seriously. The physical, social, ecological, and economic forms of violence and destruction occurring on a global scale cannot be separated from our mode of being-of-a-world. Being of a specific mode has a transformative role on reality: how we act and think co-shapes our world. Our current reality falls into a specific pattern made visible in our institutions, tools, forms of making, and systems of knowing, of which art and aesthetics play a necessary and critical role. We cannot distance ourselves from these deeply problematic outcomes.

Here is where the urgency comes from: To continue along this path would imprudent; thus, this essay is an attempt to—in broad and general strokes—challenge our most basic and implicit mode of being-of-a-world. For these practices and behaviors to change, we will have to change our deep mindsets, habits, patterns, and practices (our mode of being). Art and Culture, as I will attempt to show, occupy a necessary role in our problematic mode of being, and are thus changing them is critical to any real change.

The great systems thinker Donella Meadows put it this way: “If a revolution destroys a government, but the systematic patterns of thought that produced that government are left intact, then those patterns will repeat themselves…. There’s so much talk about the system and so little understanding…”[4]

If this quote suggests anything, is that it is simply not enough to hyphenate art (say “post-human art”) or expand its definition (e.g. social practice art). These forms of transforming art are actions that leave the systematic patterns in place that are the very problem. Taking on art is no mere navel gazing—the development and perpetuation of a category of making and thinking termed art is deeply problematic.[5] I believe that to come “after art” is a critical and creative action necessary to overturning and moving on from the historical logic and trajectory of Western metaphysics and all of its problematic eco-social outcomes.

I wish to speculate that part of what is happening with the closing of Grand Arts resonates with just such a creative inflection. That artists are twisting out from art suggests something quite new, and perhaps (just perhaps) transforms the terrain our mode of being.[6] And while it is certainly not the only place this transformation is occurring, Grand Arts is both a provocative case study, and a key site for understanding this trajectory.

- OK, so what is this mode of being-of-a-world?

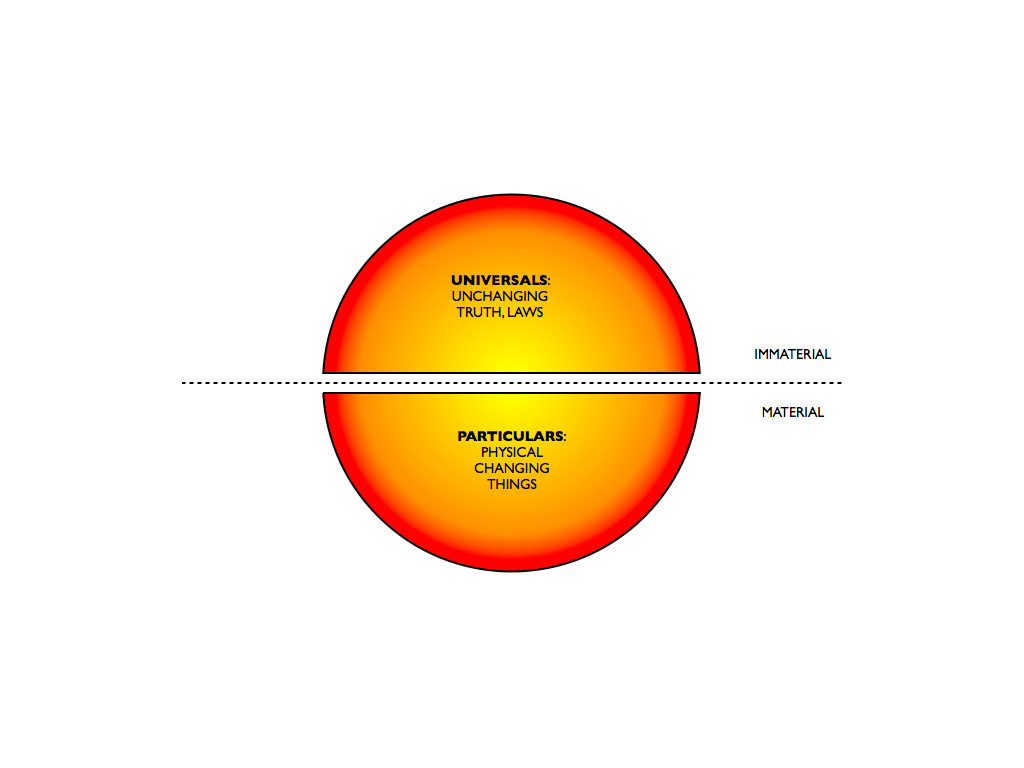

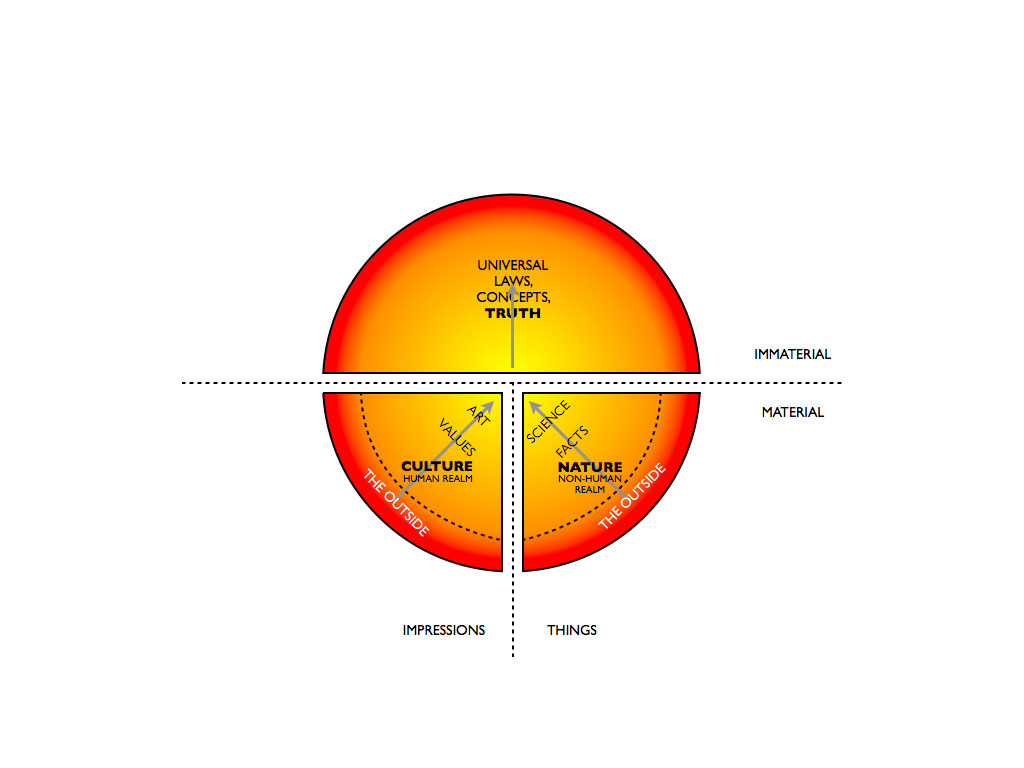

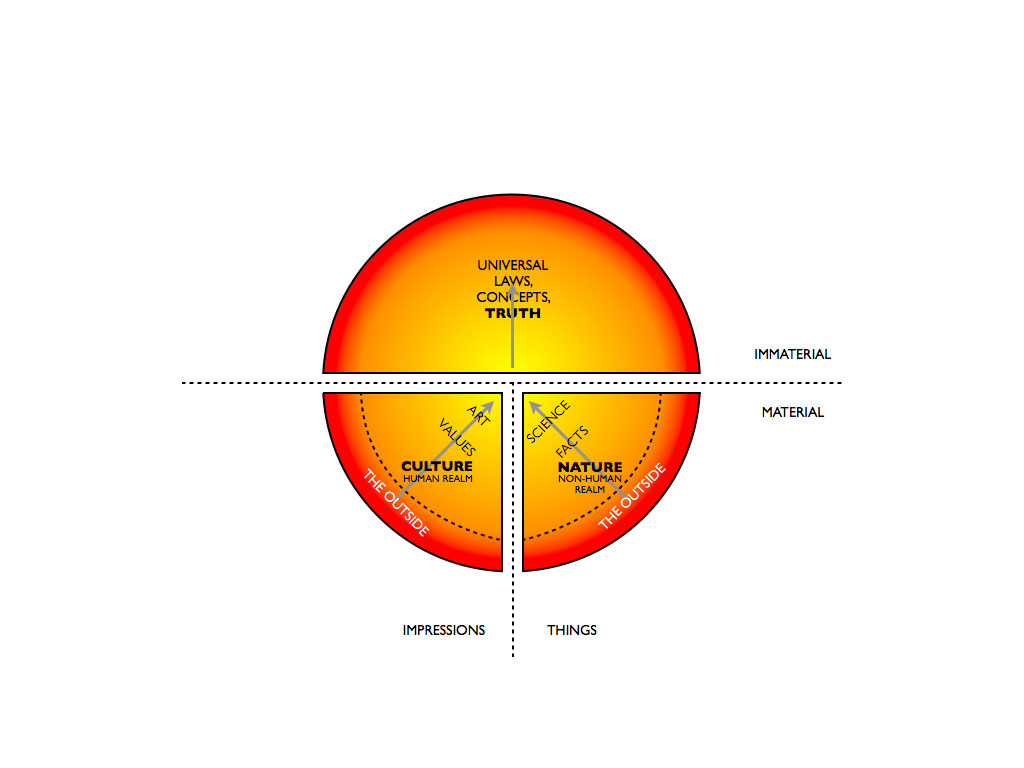

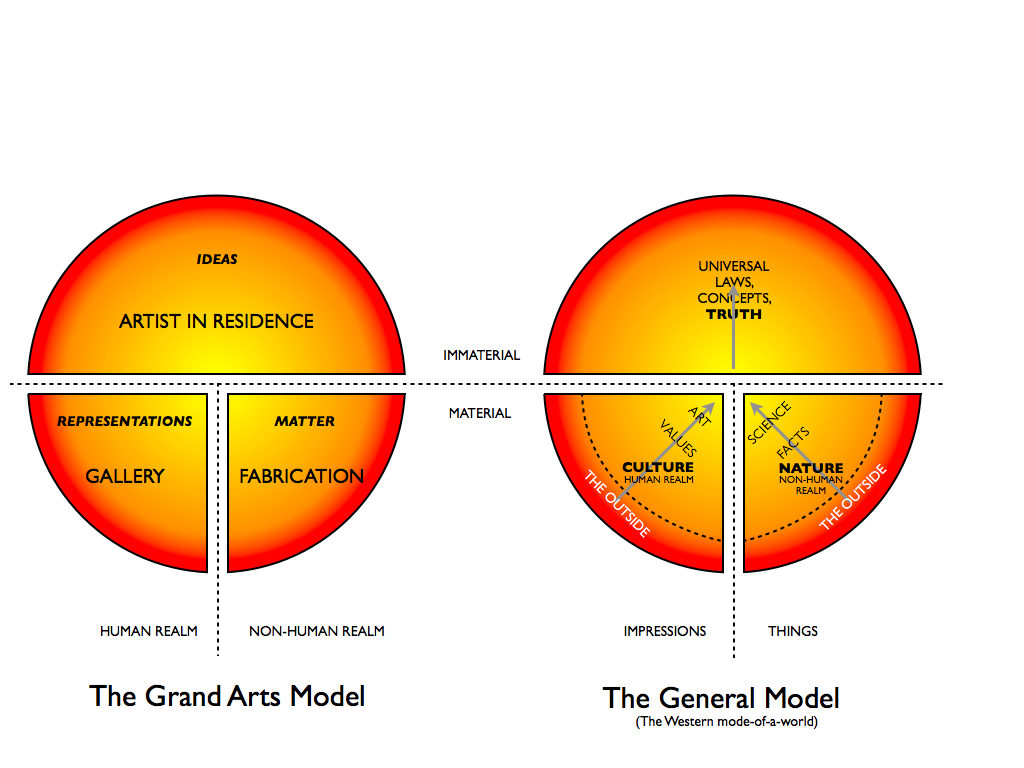

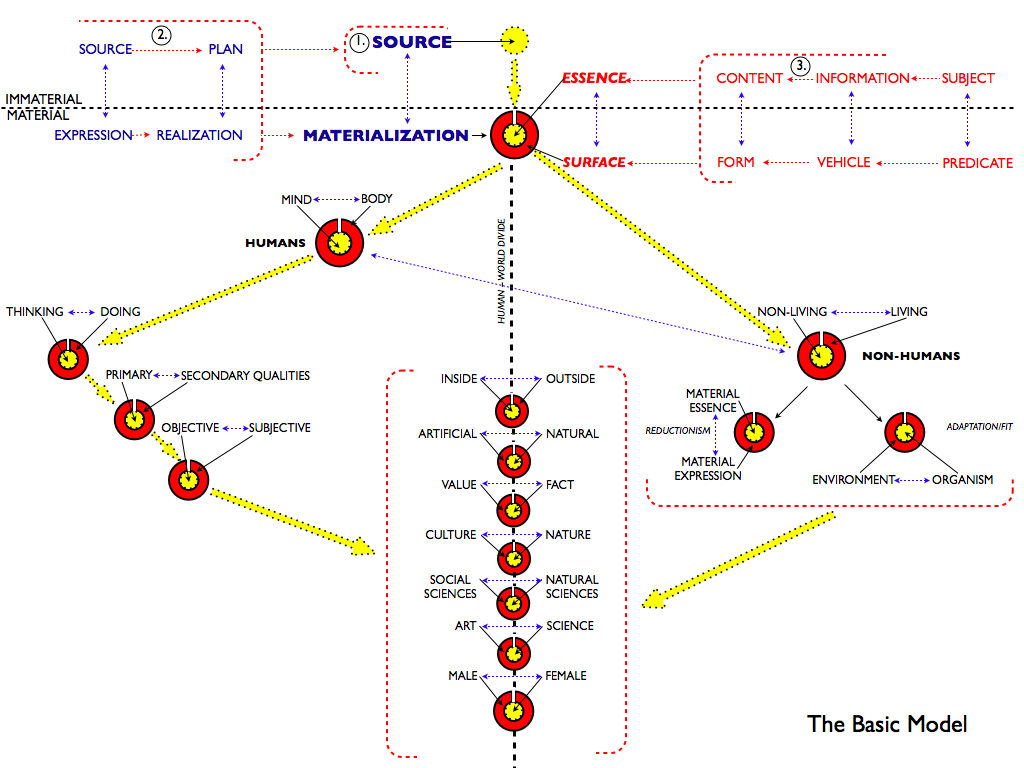

This is the critical question—and warrants going into some detail—as it allows us to understand the importance of the event of Grand Arts’s closing, and how art is deeply entangled in, and central to, our problematic historical mode of being (my hope in giving a more granular exposition is that it can serve as a diagnostic template). We, in the West, have historically developed a dualistic set of categories and institutions to co-compose reality.[7] This system, while containing nuance, can nevertheless be mapped out with a reasonable level of accuracy in a pretty simple form. It operates via two paired binaries:

- The Universal and the Particular

- Things and Impressions

Let’s take these one at a time:

- The Universal and the Particular:

This duality renders reality into two parts:[8] (1) a timeless Immaterial Realm of unchanging universal laws, truths, ideas, and concepts; and (2) a Material Realm of changing stuff (such as waves of light, paintings, and humans).

The Immaterial Realm exists outside of both time and space, making it perfect for being unchanging. The Greeks referred to this as the Realm of Ideals; Christians refer to this as Heaven (borrowing quite effectively the concept from the Greeks); in Physics, this is the realm of Physical Laws, best exemplified by TOE (the Theory of Everything—I’ll leave it to you to look this one up); in the arts, it is everything from the realm of the Spirit, or Ideology, and Concepts; and in politics, it is Human Nature, the Base (vs. superstructure), Inalienable Rights, and so on. The Immaterial Realm is a world of Universal, Omnipotent, Unchanging, and Balanced ideas. This world acts as the origin and ultimate cause (arche) for whatever is happening in the world of changeable stuff.[9]

The second half of this intrinsically connected duality is the Material Realm, where we exist as physical beings that grow old and, one day, die. The Material Realm is the precise opposite of the perfect Immaterial Realm. It is our everyday world of car tires, goldfish and bad backs. It is inherently imperfect because it is changing—mutable.

For humans, because of our mutability and consequent imperfection, we are always striving to match, reconnect, follow, or fuse with something unchanging, perfect and true that resides in this other (immutable) realm. This logic sets up a reality in which we are always lacking something—endlessly striving for a wholeness that is outside of this mutable material world. It is a recipe for permanent failure—striving for that which we cannot really access because we are but fallible material beings permanently exiled from the immutable realm of truth.

The problems with going down this path are numerous. Here is an abbreviated list:[10]

- Binaries lock us into a closed set of fixed outcomes: all positions, one position, nothing, or (4) the “in-between.” There is no outside. We perpetually toggle back and forth: purifying, fusing, negating, or occupying the middle ground. Nature vs. Nurture. Matter vs. Spirit. Base vs. Superstructure, art vs. Commerce. Trans, Bi, Quasi… Done.

Even as binaries have two terms, only one really counts. The second one is always the inverse of the first—the pure and the not pure (impure), light and the lack of light (darkness), white and not white (black), men and not men (wo-men)—or, in the case of art: matter or concept (spirit, truth, etc.). The desire to fuse one half of the duality into the other as a solution to the problem of binaries (art into life, or “Everything is Nature”) merely extends the unitary logic of binaries, and as such simply perpetuates the binary system. Open systems are unimaginable, and complex ecological entanglements cannot occur (nor can complex historical developmental models of change be imagined).

- The Two-World Model is a process that divides reality into two realms, then removes one entirely from access/change by us (the Universal), and as a final step makes the second realm fully dependent on the first. This model gives us a basic stance toward life: always look outside to some elsewhere that is more real (unchanging) for the inaccessible truth of your (or any) being. We become inherently detached beings—merely “in-the-world” but never “of-a-world.” Creation is derivative of some fixed truth that is inaccessible and elsewhere. Stasis is a given. Critically, stasis allows us to import the unchanging realm into our historical, evolving reality. Terms like “human nature,” “art,” “Nature,” or ideas (such as “art reflects the universal truths of the human spirit”) are all models of this re-importation. These unchanging ahistorical universals makes it impossible to deal with any dynamic situation, our entangled reality, or understand the fundamental creative logic of reality on their own terms because we are always looking to an elsewhere for a detached world-free answer.

- Binary perception is always at a distance (re-presentation). We are always in one world looking for access to another for the truth. This means that our implicit mode of being is both a re-presentation of something else (some universal truth) and a mode of striving to engage with reality as re-flection and re-presentation of something else (this universal truth). We are fated to live removed from the world, striving to get it right somewhere else (see “Things and Impressions,” below). The optics of perception-at-a-distance becomes our key model for engagement —one that is critically re-inforced by the visual arts and “visual culture”).

- Stasis and balance become our way of locating and recognizing truth and reality. When truth is modeled as unchanging, we both strive for it and judge existence in terms of stasis with balance or harmony being the ne plus ultra of stasis (obviously, the inverse is also just as active in our imaginations). The trio of stasis, balance, and unchanging truth reduce time, change, and process to the movement of pre-existing things (toward perfection or into nothingness). The most important things (truth and universal laws) simply statically pre-exist, awaiting our harmonization. This position is profoundly antithetical to qualitative forms of emergent and evolutionary change. Within the model of stasis we have no way of understanding processes, emergence, or dynamic systems.

- Discreet things become the focus of our conceptual, perceptual, and material practices: with truth being a discrete, singular, bounded, unchanging entity, we see reality on similar terms (reality as a set of nested objects). This is connected to the transcendent space of truth, which removes agency from these objects (placing it in another realm and making objects a type of brute matter obeying universal laws).

- Onion model: This analogy is the conceptual model of this system that is nearly ubiquitous. Surface and essence. Onions peel away in layers until you get to the core. Layer by layer you move from the surface and the superficial to the core and essence. Everywhere we see this desire to strip away the inessential, the trivial and reveal things in their inner essence. But what is left? Reductionism, another name for this model, reduces the directly engageable (material) aspects of anything the expression of a deeper (immaterial) core purpose/essence/soul.

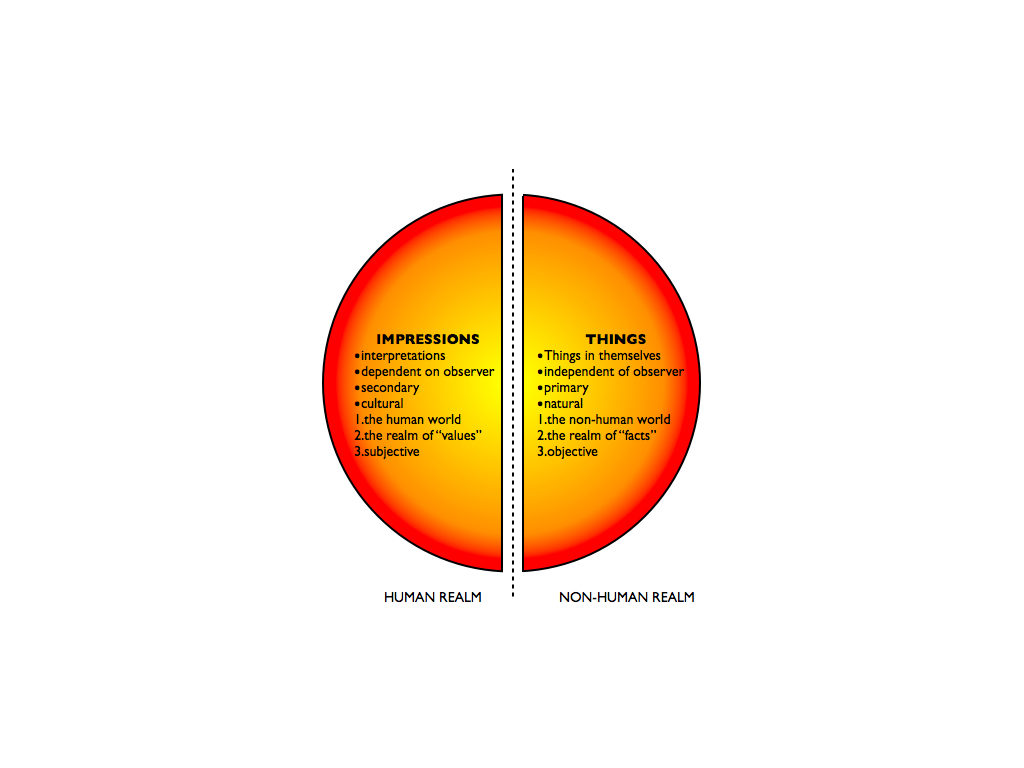

- Things and Impressions:

This second duality is used to bring us into the equation. We, it is claimed, have a unique relationship to reality: while we live in the world of things, we cannot know these things directly—we can only know our sense impressions of these things. Thus reality can also be divided into the stuff “out there” and the stuff “in our heads.” Things and Impressions:[11] the part that is independent of us (Things) is considered primary and the part that is dependent on us (Impressions) is considered secondary.[12] Hence this division is also called the primary/secondary duality, which also has ramifications for our experience of things—for we can sense both “real” or primary qualities (solidity, extension, motion…), and the secondary qualities that are merely reflections of our subjectivity, or style of cultural interpretation. A quick example is in order: as students, artists are taught that Color is not “in things,” it is in us, because it is dependent on our eyes and how they work, as well as on light and its diffraction. The conclusion that “things are just in our heads” leads to what should be a disturbing outcome: the beauty of a sunset is really just in the eye of the beholder—we are not in the world—we are just in our heads…

At it simplest, this divide perpetuates five problematic divisions:

- Being and thinking: There is always a correlation (whatever it might be) between being (a thing) and thinking (a human). But why keep this arrangement in place? Thinking does not need to be of anything (nor is it particularly human). Could the aconceptual thought of plants[13] offer an alternative model?

- The human and the non-human: Dividing reality in this manner locates us in a unique and separate category of human subjectivity—one that we call Culture, while producing another distinct category for the rest of the world: Nature. The argument is that we are the only creatures who have fully critical, self-reflexive sense impressions and this unique psychic, social, economic, political, and rational human essence is what justifiably separates us from the rest of reality. Nature is posited as objective matter (the rule-following world of plants, animals, and matter). Through this logic, our mode of conceptualizing reality swings between the poles of cultural relativism (subjectivity) and full naturalism (objectivity)—that is, Humanities vs. Science.[14] It is with the development of this foundational dualism that art truly comes into its own: art is positioned as both the exemplar of Culture and its critical gatekeeper.

- The subjective and the objective: This pair is our primary means of formalizing and activating the divide between us and the world “out there.” It is an extension of the Nature vs. Culture dichotomy: not only are we, as a species, radically separate from the world (Nature), but also as individuals we are locked into the limits of our subjectivity—we are “trapped” in our heads (I think, therefore I am). There is a paradox here: despite being locked in the human world, we have a unique form of access to the true nature of things (objectivity). Science provides the methods for this access. The world is thus composed of two realms: what can be known factually: Objectivity (via science), and what can be known subjectively (via artistic/cultural practices). We are beings whose ultimate task is to “get it right,” which means express the world and the self accurately by keeping the subjective separate from the objective (and Nature from Culture).

- Facts and values: This duality operationalizes these forms of knowing (subjective and objective). Facts are grounded/fixed by the things out there (ultimately in The Universal of the first set of binaries). Values come from our subjective sense of things, and as such are grounded only by our subjective sense of things. In this model, you cannot go from a fact to a value. Science alone deals with facts; and cultural activities such as art, ethics, and politics deal with values. Facts can tell you what is really happening, and independent values can tell you what to do about it. Just like the red of the sunset is merely in “you,” your values are merely in “you.”[15]

- Things and relations: The things/impressions duality further implicitly privileges discrete things as the most basic constituent of reality. Processes, events, and relational qualities are all secondary outcomes from the world of things. With stable, given things as fundamental, process becomes not only secondary but also detrimental—a diluting, a mixing, a diffusing of the original purity. Being and not becoming. This distinction ultimately conscribes us to see the world consisting of discrete things fully separate from us and to live exclusively in our sense impressions.[16]

The most general expression of this division is our paradigmatic worldview of Nature vs Culture.[17] Nature equals all those things “out there” and separate from us humans. Culture equals all those things that are simply our interpretations of what is out there. Nature is asocial; culture is a set of mutually exclusive cultures. art falls quite neatly on one side of this divide[18]: It is a human, subjective, cultural form of expression (whether it deals with sense impressions, ethics, or politics).[19]

Once we put these two dualities together, we have an overarching diagram of the operational logic of this mode of being-of-a-world:

- OK, I can see how all of this comes together, I get how all-pervasive it is—but can you say more about the role of art in all of this? It is still pretty unclear to me…

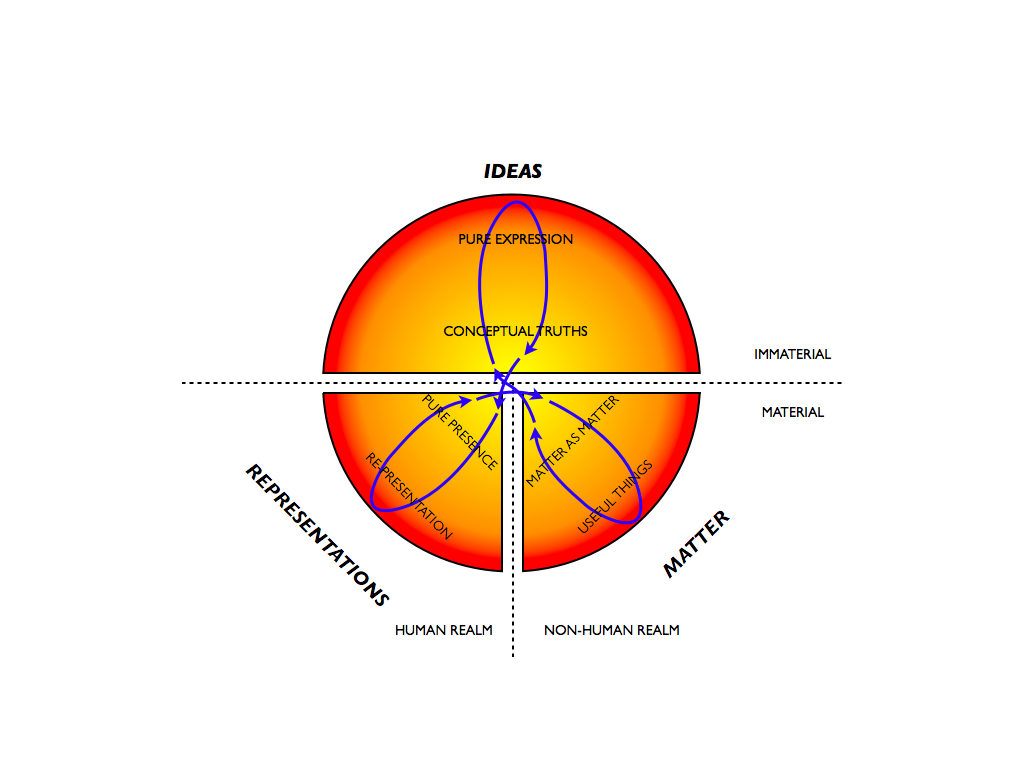

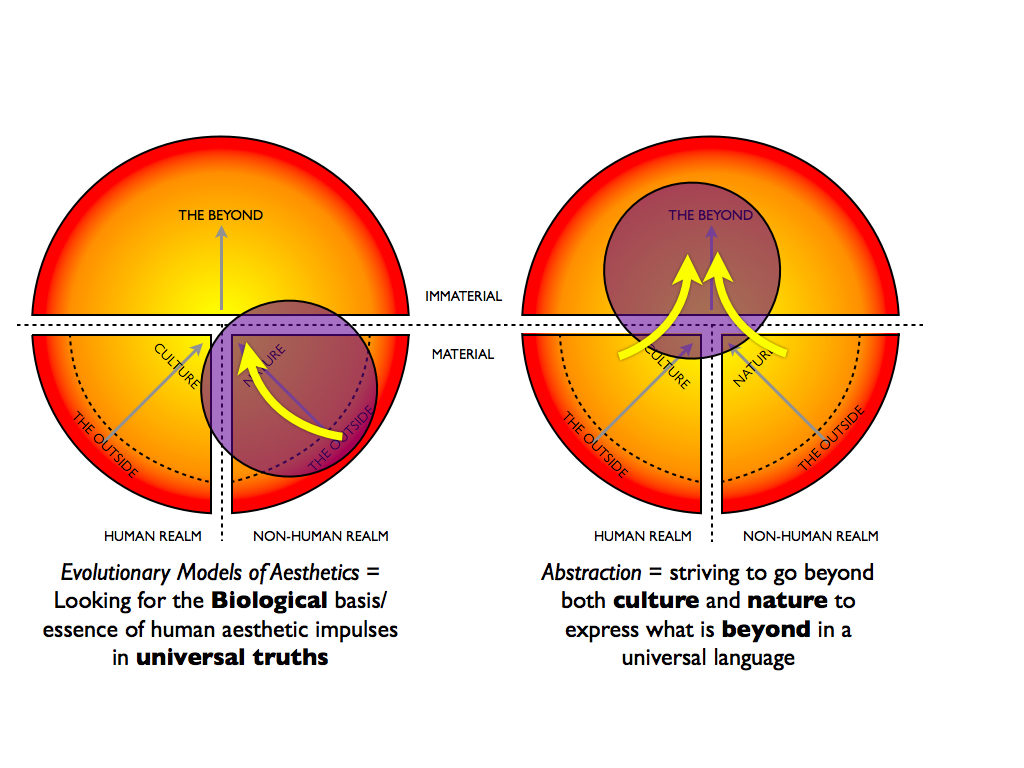

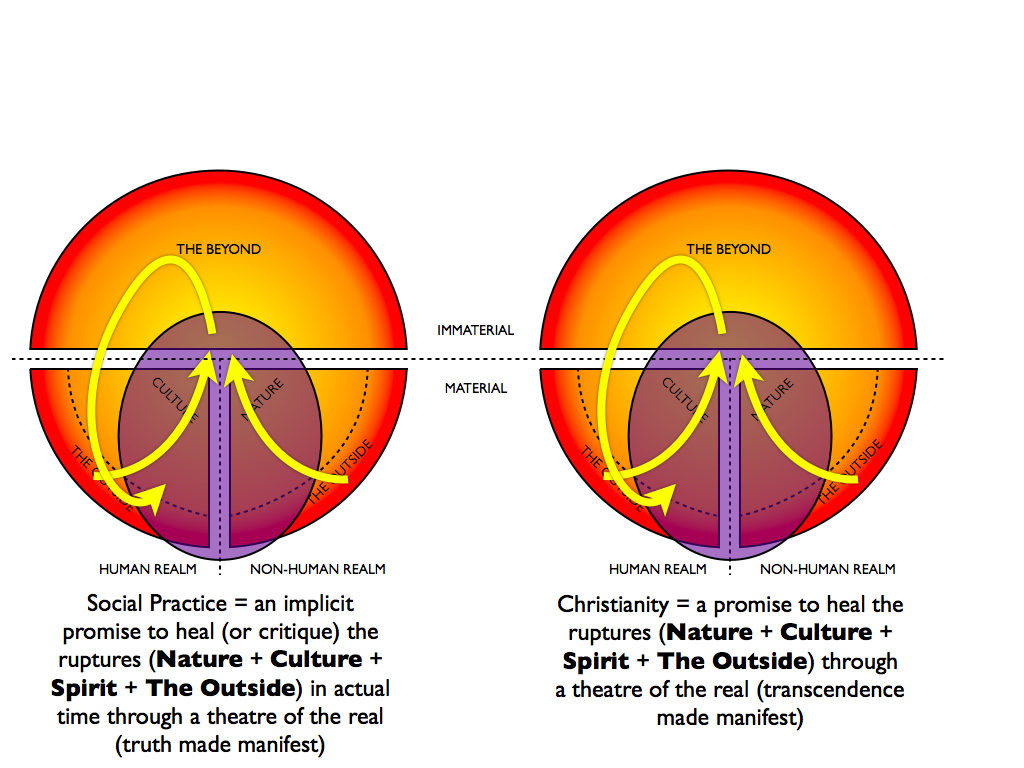

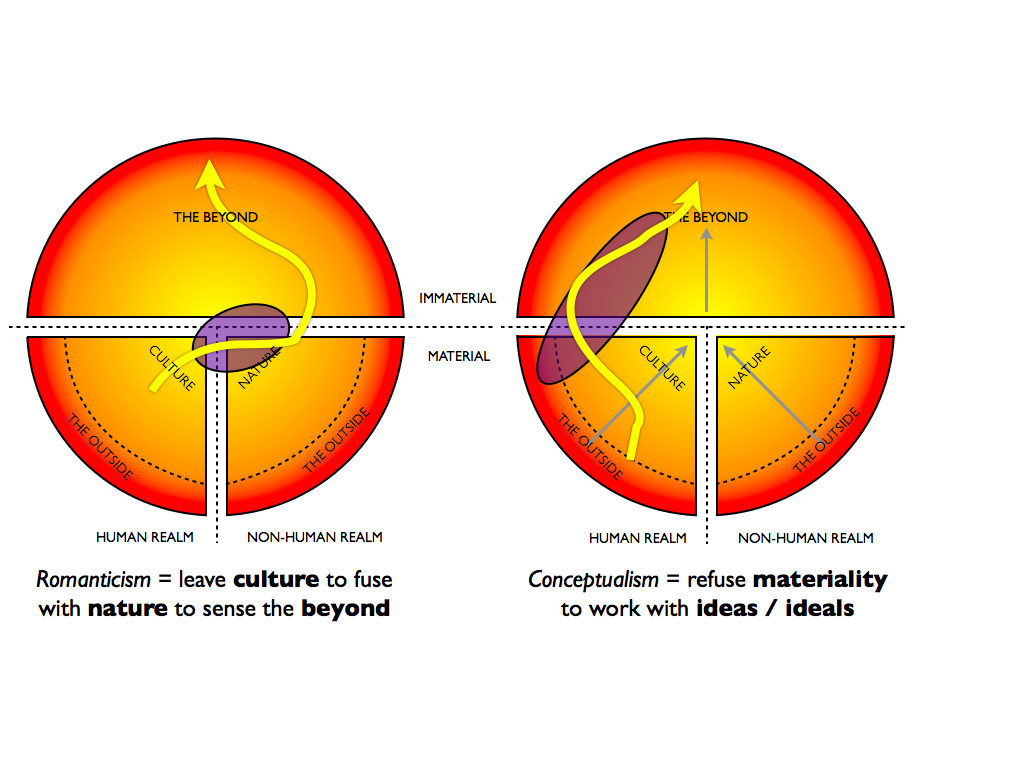

Sure, but let me first note that we are in something of an odd situation today: this mode of being-of-a-world has recently come under a brilliant flurry of critiques that manage to effectively set aside the binary logic of this mode of being and develop rich cosmological alternatives.[20] There have been very powerful critiques of Nature, especially from fields such as anthropology and ecology; the logic of Culture has been critiqued in fields like embodied cognition; and the realm of the immaterial has been taken on by everyone from developmental systems theorists to process philosophers. But art, to a large degree, has gotten a pass. Perhaps because of contemporary art’s seeming plasticity. It can become purely conceptual, or political, or all about matter, or a forum for critical reflection on other practices, and on and on… But this seeming catholic sensibility, and plurality of “arts,” hides the singular logic of a larger pattern that we have been discussing. art can mutate in these manners because it sits at the juncture of Culture/Science/Truth:

Art operates by moving across these boundaries, reversing dualities, or claiming the in-between. And with each reversal, art becomes something different (Minimalism vs Formalism vs Abstract Expressionism vs Conceptualism vs Social Practice). But these are not arbitrary or freely formed transformations—what propels all of these differences into action is the unified set of procedures at the heart of this mode of being (our two lists above). art’s revolutions and internal transformations are—to a very large degree—predictable moves in this pre-prescribed landscape.

From this central position, art is critical to the production and grounding of human exceptionalism (in all its diverse forms). Additionally, art, in all of its diversity, is our most effective tool for the production of a human subjectivity as separated from a muted and pacified world. art, at a structural level, is a key engine for the Western construction of reality as elsewhere, and for the production of a consequent theatre of the healing/bridging of this self-constructed divide. It operates as an idealized theatre for the double binaries to re-inscribe any new event within their logic.[21] All problems/curiosities/questions ultimately come from, and are resolved by this schemata. art is not a reducible singular modality of division and healing.[22] Examples of these scenarios playing out are as numerous as there are forms of art. I briefly map out of a few to give you a sense of how this logic activates the larger structures of our mode of being-of-a-world:

- That is a pretty strong indictment of art…

Well, it is, but to be fair it is a larger indictment of our mode of being—art is just a key part of that. Let’s jump back to the big picture and look at the role of Culture as the larger terrain within which art operates. Culture, as a procedure, generates a way of being-of-a-world that makes us experience the human realm as a subjective interpretation of reality (a reality that is never fully accessible). This procedure instantiates each Culture as a unique subjective interpretation of reality. When each Culture is positioned as having a distinct interpretation of reality (none being necessarily better), the catch is that our Culture is the one culture that understands this situation that we are all locked into our subjective positions. These subjective interpretations are to be understood as grounded in nothing but themselves (a particular outside) or as the expression of some deep evolutionary process (a universal outside). Within this terrain, art exists as the ultimate cultural practice, claiming the most full, direct, and complete individual (cultural or personal) space of expression or interpretation (true access to this outside and the ability to bridge the gap). art is the apex of Culture (see above diagram).[23] art, as a procedure, serves to validate the entirety of the framing of humans within a Cultural terrain, grounded in Nature itself, all of which is further grounded in Universal Truths.

Every aspect of this mode of being and its procedures has been shown to be fundamentally problematic.[24] Nature, as a uniquely non-human realm, does not exist. Reality is not composed of things or essences. The world is not striving for balance, stasis, or stability. Humans are neither unique nor separate from reality. We are a complex, distributed multi-species association that extends far beyond our bodies. Producing procedures to frame reality in terms of a quest to discover singular non-constructed truths in an immaterial realm (while maintaining a division between the human and the non-human world (Nature) has made us willfully blind to the eco-social costs of such a framework and the genuine absurdity of this mode of being-of-a-world.[25] These procedures, with their focuses on outsides, things, purities, stabilities, and human uniqueness, mean that we have few tools/procedures to see things as the emergence of dynamic systems and complex multi-scale/multi-species collectives—but that is a story for another day…

- OK, so art is deeply entangled in a particular mode of being-of-a-world. How does this mode of being actually impact Grand Arts?

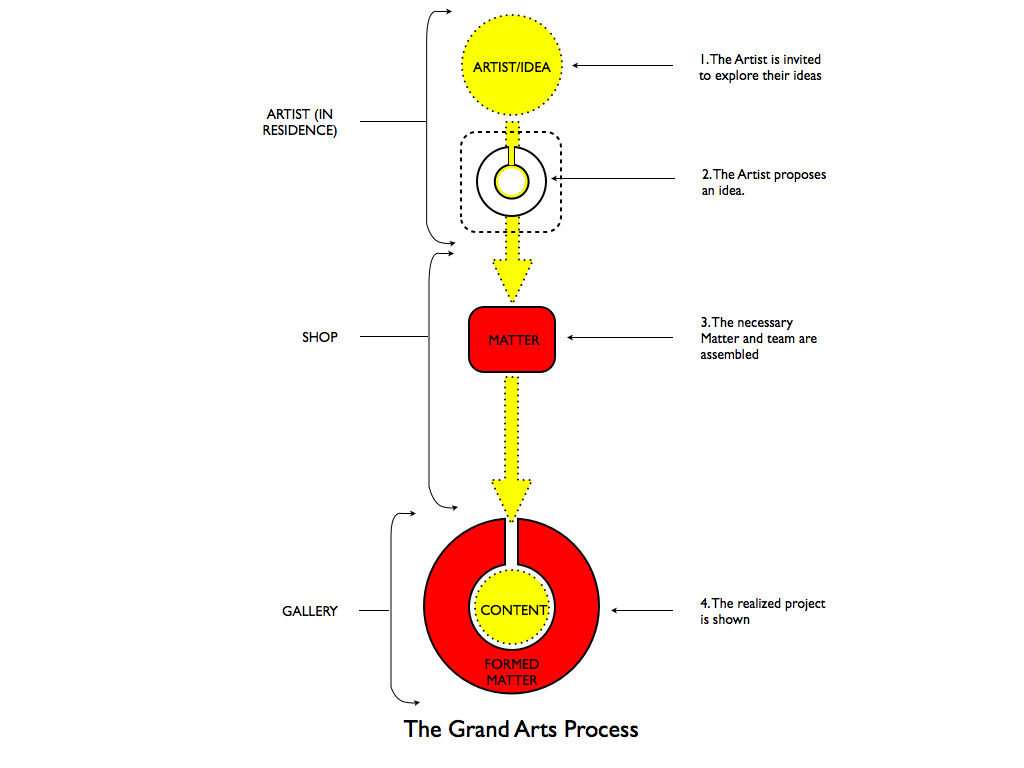

The original vision of Grand Arts was twofold: to be a place to help artists make large-scale work that they could not otherwise realize, and to allow audiences to experience the process of such works coming into being. To foster this vision, a new building was designed in which the spaces of making and exhibiting would be equal and open to the public.[26] Thus, as you enter Grand Arts, to the right, swinging doors lead to a 5,000-square-foot fabrication shop, and to the left is the entrance to a similarly proportioned gallery.[27] Opposite the entrance is a staircase that leads to an artist residence and the open staff offices. Both in vision and in concrete spatial organization, Grand Arts would provide artists with three things: first-class housing to host artists’ idea generation, a shop that could make nearly anything,[28] and a state-of-the-art gallery in which to present work. The artists would provide the ideas, the shop would build it, and the gallery would display it.

In essence, Grand Arts could be divided into three equal spaces: gallery, workshop, housing. Here you have a very clear fit between how a set of procedures operates abstractly and how an actual institution is co-shaped by this mode of being-of-a-world. We can see both in aspirations and in architectural layout this fundamental logic of the mode of being-of-a-world: ideas, things, and interpretation.[29] The mode of being becomes the institution. And the institutional logic implicitly reproduces the mode of being.

What made Grand Arts both unique and successful was its process of making, which began by strategically choosing to be an organization supported by a single patron and run by a single director. With no outside funders, committees, boards, community, or even viewing public to answer to, programs could be realized in a free and direct manner. A streamlined process of creation developed: (1) an artist was selected by the director; (2) the artist was invited to develop a proposal (Ideation); (3) the production/fabrication team evaluated the proposal and developed a plan to realize it (with the selection of materials and processes); (4) the work was made, via trial and error, in an effort to reproduce the artist’s vision as best as possible; and (5) finally, the work went on display. Then the system reset to neutral and began again with the next art project.

This whole process was connected to the economic model of the gallery system. The artist would not be paid a fee for the work, time, or exhibition at Grand Arts, which made sense because the artist walked away with a substantial and highly valuable object—one that could not otherwise have been made— to take into the gallery system.[30] What would be covered were all expenses for living in Kansas City and for realizing the project. In this, Grand Arts made how well it took care of its artists a point of pride.

The list of projects realized is truly remarkable. Beth B made her first monumental sculptures; Jane Lackey evolved from fiber threads to chromosomal threads; Mark Cecula developed a huge, multi-stage porcelain carpet; Patricia Cronin produced heroic public political sculpture: Memorial to a Marriage; and Rosemarie Fiore’s Good-Time Mix Machine utilized an amusement park ride to make drawings on a wholly new scale. Gesamtkunstwerk was in the house.

- OK, but what’s the connection between this institutional process of conceiving and making art and the Western mode of being?

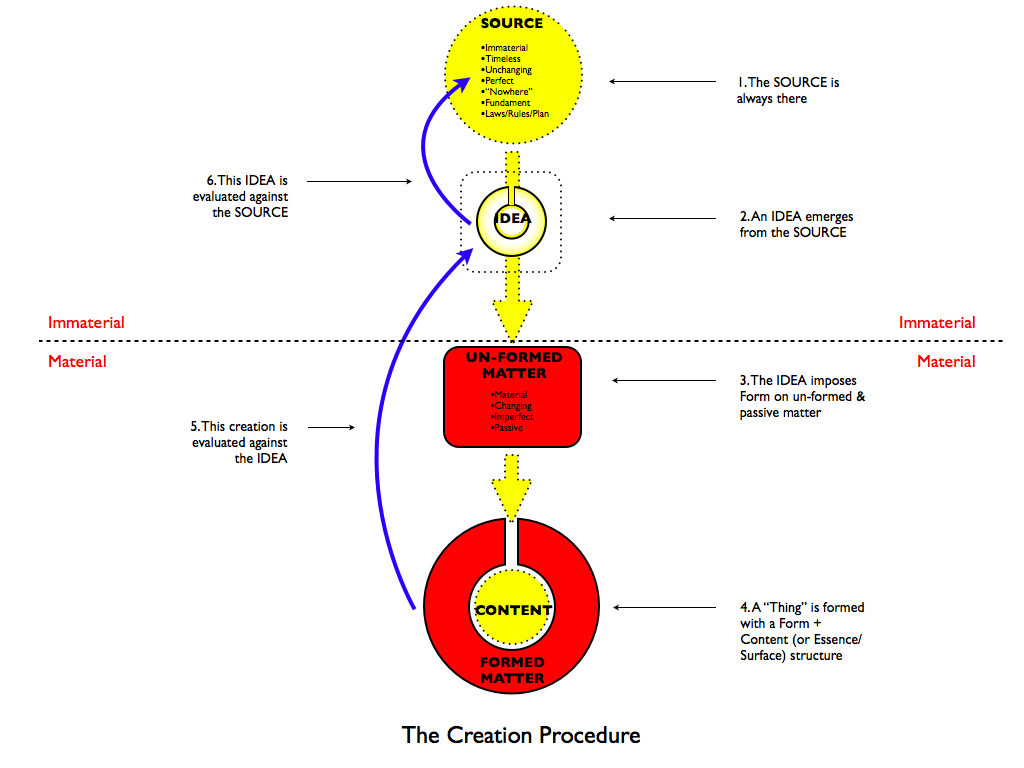

First off, we can see that this process reproduces the immaterial/material divide, with the privileging of the immaterial realm of ideas (Ideas always come first and are best developed independent of real material considerations). But we can dig far deeper into this process by tracking how closely the Grand Arts model follows the making procedures of the Western mode of being. The Western tradition espoused a heroic model of creation long before Picasso, Pollock, or the contemporary Gesamtkunstwerk approaches of Grand Arts. This creation model had established itself long before the beginning of art. While emerging within a Greek milieu around 600 BC, this model is most clearly recognizable in its Judeo-Christian form found in the book of Genesis.[31] The story is well known: A god who exists outside of reality creates everything over seven days and then bequeaths us a special dominion over it.

Let’s go through this step by step: (1) The creation procedure within the Western mode begins on the immaterial side of things with a “source” outside of the world (literally outside of everything: in the case of the Christian God, he is truly nowhere). The source, origin, arche has always been there; it is a type of infinite font of creativity; (2) From this god, or font, springs an idea;[32] (3) The idea or plan is materialized via finding the right medium, material, and techniques to carry out the vision as precisely as possible. In this process, one is looking for a form that could be molded to carry the message/intention that the creator/source wishes to present/put into reality. This is the heroic part of the process—the seeing through of a plan that requires imposing one’s will on brute matter for the sake of the ideal. One cannot rest until vision and reality match. This act of making is the forming of a vessel—a delivery vehicle of the vision/intention/message;[33] (4) Finally, what you have made is always evaluated against what you had “in mind” —against the ideal. The actual is always a “compromise”: Money, materials, time, and other “outside” forces stop you from realizing your vision.[34] As should be apparent, Grand Arts’s institutional organization, work flow, and architectural structure track this procedure pretty closely.

- That is quite a coincidence, but what is the problem with this methodology?

Well I doubt this is a coincidence. But to address your question: This methodology of making is the procedure by which the full set of dualities is actualized, developed, and sustained. It is that simple and problematic.

- At the beginning you said that these reflections were brought about by a shift at Grand Arts—can you say some more about that?

Grand Arts’s Shift

The way of operating Grand Arts began to shift around the time Stacy Switzer joined as the new artistic director, in 2004.[35] The most important and relevant shift for this discussion was the reframing of what Grand Arts did—from supporting artistic practices to supporting research creation.[36] This evolved in a loose and indirect fashion—more of a trajectory than a project, per se.[37]

What this means:

- Research projects by definition have an open relationship to their outcome (they are not the execution of a plan or vision), so the focus shifts to processual and iterative activities —following rather than leading.

- Research projects at Grand Arts were given enough leeway not to have to think of either outcome or “producing a work of art” (especially in their initial phases).

- “Creation” became a tool to leave the framework of “art”—operating both as a goal and as an emergent method—but always explicitly connected to the larger question about how we understand reality, organize our lives, and engage with the world around us/in us.

- Aesthetics became redefined from an art focus to what we can sense, feel, and experience—so as to transform who we are, and what we see and know. Research creation became the methodology to develop the tools and procedures to undertake this experiment.

- This shift to research creation was not simply an expansion of what counts as art. Research creation was understood as a strategic moving outside of the Western mode of being to the degree that it allowed new forms of collaboration to happen that ignored the double divide.

- New consultants, collaborators, and institutions were brought into the mix (these exceeded the human, models of communication, and the willed passivity of things).

- Projects often had little to do with the arts in any direct manner (or its sites and circuits).

- Things began to show up further and further afield—underwater in the harbor of Alexandria, Egypt; at Russia’s cosmonaut training center; on frozen lakes high in the Inuit territory of Nunavut; an anarchist ice cream truck was sent off into the world; and work appeared at the edge of space.

- New logics of making developed (which were far more distributed) to agents beyond the human: plants, animals, neuro-receptors, and ecosystems. Emergent, unknowable outcomes were cultivated as ecstatic music concerts became the seedbed of practices. New forms of engaged actions were plotted as labs, from IFF (International Flavors & Fragrances, Inc.) to the Land Institute.

- The outcomes of creative processes ranged as widely: making systems, facts, linkages, ideas, pragmatic products, research, and new economies.

Examples of these experiments fill this book, but here we cite a few places to start an exploration:

- Sissel Tolaas’s two exhibits fused the extended body to landscape and politics via the bio/geo/social logics of smell—beneath, beside, and beyond the subject.

- Tavares Strachan fused deep oceans and regions of outer space to geo-political spaces of North/South in order to develop a space and ocean research program in the Bahamas.

- Cody Critcheloe and the musical group SSION engaged in a sustained production of new queer cosmologies via extended music videos.

- The two group shows, Ecstatic Resistance and Fat of the Land, experimentally re-entangled the bio-geo-social in multiple manners.

Grand Arts paid close attention to all of the inflections that came from projects affecting their own structure (pop music and videos, popular cinema, neurobiology, ecology, politics, social actions, economics, deep time), such that its interests, engagements, and extended community of fellow researchers began to read like a series of tests in as many institutional and structural directions as possible—or what it looks like when one simply ignores the prevailing logic of the Western mode of being-of-a-world with a joyful naivety.

Practices really changed as the activities became less connected to the gallery, the shop, or even the residence. With artists and others wandering the globe, working with vast and diverse networks of collaborators, these new practices no longer fit the original structural model of Grand Arts. That Grand Arts’s collaborations more and more often left the organization’s physical structure should come as no surprise. For the Western mode is not simply a framework of thinking—it is enacted in our spatial practices, buildings, furniture, and institutional logics (as Grand Arts has shown us). These materials are not the manifestations of a framework but key agents in its production. These physical structures, policies, and practices are more effective and hard to change than ideas or ideologies.

Change can only sidestep these physical components for so long. The trajectory of research creation relies on the institution’s ability to learn and transform from the practitioners and practices that it invites. One of the paradigmatic limits of art institutions is that they place a moral and ethical value on not changing.[38] The institutional ideal is to present each artist’s vision as fully, completely, and authentically as possible. This ethical concern means that the institution must necessarily default back to neutral between each artist (e.g., a Marxist project one month, then back to neutral; then an expressionist painter, back to neutral; and then a formalist …).[39] The argument goes something like this: If we form attachments to one vision, we are showing a preference, and then we will no longer be able to show all visions equally. The model of non-attachment is an ethical vision of cultural fairness. This defaulting to zero means that the structural and physical changes upon which research creation relies as a model is ethically out of the question for an art institution.

This default structure is that of the Western mode of being, and what the Western mode of being implicitly whispers at this moment of resetting to zero is no attachments . . . no obligations . . . And this is precisely the meaning of Culture (and art) within the Western mode of being: whereas Nature is asocial, Culture is a set of multiple, mutually exclusive interpretations of what it cannot reach (Nature or The Ideal)—and, as such, we need to treat them all equally well. Culture becomes a flipbook of (inconsequential) options to bridge divides. And being “cultured” becomes a well-heeled ability to flip through a Rolodex of knowledge without attachments. art and being cultured teaches us how to love but not care. We are moved, and we move on. We form our subjectivity as a set of ever-flexible lifestyle choices. We collect subjectivities as much as any institution displays them. The art institution becomes the enlightened display venue for the spectacle of the ethical entrepreneurship of a culture’s competing authentic visions.

But what happens when one feels the ethical pull of attachments stemming from a new event? Do they just disappear into personal friendships, documentation, and PhD theses? Can what precariously emerged during an event be taken into account if the event disappears after a month? Does everyone just go home? (How can a “new” event go “home”?) Sadly, at a structural level, the standard art institutional answer is yes (and show up on Monday ready to start as if from zero).

Grand Arts stopped being the kind of place that could accept this procedure. It co-made events and held itself accountable to the adventure of being responsible for what showed up. At some point, a new quasi-structure overturned what was there to begin with (the institutional logic of the Western mode of being writ large). But structures are not so malleable. Institutional logics and the procedures of our mode of being do not come off like a pair of pants. New communities, events, ecologies, and long-term projects emerged that required a continuing community of mutual support. The structural model could only flex so much.[40] Grand Arts quickly had to face a bifurcation point—go back to being an “arts center” defined by the reset button or do something else. We have seen the first answer far too often: the Met’s continued expansions, MOMA simply shoehorning histories back into the structural logic and forms of engagement that the “modern” can claim as its own, and even progressive centers becoming expanded conference centers for yet another rounds of lectures (mainly to artists on how to rebrand themselves as activists, ecologists, or sociologists). Closing is thus not admitting defeat or failing; indeed, closing in this context is the creative desire to actually do something else. This is what is worth celebrating—closing becomes quite an adventure in the face of these immortality empires.[41]

- Could we not simply utilize all of these alternative procedures to transform art? Are you not simply throwing out the baby with the bathwater? Can’t we still keep art, and make it work differently? Isn’t that what we have always done?

A large part of the idea that we could just reform the concept of art hinges on imagining that it both is a discrete realm and has few implicit structural issues to confront. art, as a set of procedures, does not come alone. It is a critical part of the Western mode of being-of-a-world. The problems with this mode of being are clear. The structural issues—the medium of gallery + museum + fairs + biennials system, along with its systems of making, circulating, and self-reproducing—its total ecology is a critical aspect of our mode of being, and the problems with these structural aspects should be just as apparent. I would like to suggest an experimental hypothesis: We can move on. The desire to still be part of art is a symptom of what Nietzsche was calling our inability to defecate—to digest, process, mutate, and continue. We can. And those who wish to keep to regurgitation and re-chewing art—well, those dietary practices do not need to be our issue. We are not beholden to these institutions, structures, or habitual procedures. We can look to the experiment of Grand arts and the adventure that begins with the closing of Grand arts. We can develop new institutions, boundaries, habits, practices, embodiments, techniques and, above all, procedures. We can come after art (and this means coming after Nature and after Culture—after our current cosmology).[42] We can develop new cosmologies—not the right or final cosmology—but multiple, provisional and experimental sets of new procedures.

This call to experiment with new forms of being-of-a-world and to develop new procedures is not a call for the return to mental spaces of pure ideation (to sit down and brainstorm ideas, or set up think tanks is simply jumping back into old models). We need to link new forms of doing to new tools, to new environments, and to new forms of thinking as a total structure. This development of a new mode of being-of-a-world begins with questions of composition. How do we co-compose new collective practices, systems, and ecologies? It begins with our bodies, habits, practices, traditions, environments, and tools. It begins with how we organize our institutions, how we circulate, and how we take into account what newness shows up. How do we work with the many others beyond the human and at many differing scales to make these experiments possible?

- I heard that you presented this to the folks at Grand Arts—how did that go?

Yeah, that was a bit crazy, and quite contentious. About a month ago, as I was finishing the formulation of these ideas, I was invited to present them to the extended Grand Arts community. This took place as part of wonderful freewheeling multi-day retreat considering the future/legacy of Grand Arts. I began my presentation in the early evening and things were going strong past midnight. The discussion was a complex and challenging one. I was quite surprised by how important the idea of an ahistorical universal art was to people, how strongly artists held onto the “necessity” of art, and how deeply our identities were tied to a desire for purity as authenticity. I realized that, for me, making an argument was less critical; what mattered more was for people to feel a curiosity to entertain the idea of an alternative future. I left the retreat and went home to rethink this essay with ideas from the discussion, with the goal of being able to present the outlines of a speculative alternative:

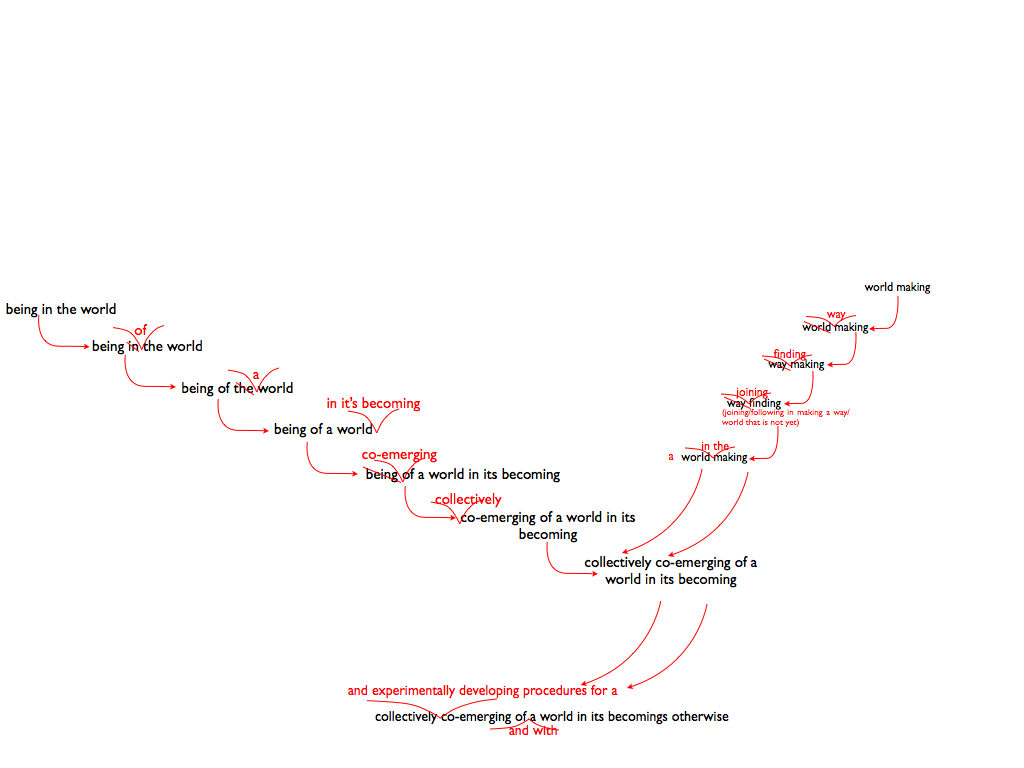

- Adventure: Although this is a critique that outlines serious problems with our mode of being-of-a-world, this is not a call for a style of change that takes the form of a “crisis” response. Such a call would push us into forms of management that end the possibility of experimenting (e.g., with the energy “crisis” and the environmental “crisis” comes the crowning of a new set of experts, management techniques, and scarcity production that harness us to immediate necessity of “solutions thinking” and the rapid carrying out of “answers”). We need to have the creative will to work differently. Adventure, ironically, requires a modesty—it does not claim a solution, or a plan. Adventure requires a resoluteness to embrace the precarious openness that is inherent in creating differently, that asks of us a willingness to become responsible to what emerges[43] (including ourselves). All of this is less a project (of “overcoming metaphysics,” say) than a trajectory. A trajectory in the sense of a “heading” (how when navigating one follows a heading—toward, but not to, “that mountain”). Let us move into the adventure of wayfinding in waymaking sensitive to the emergence of new problems worth having and new worlds worth making.[44]

- Nurture attachments: We do not need a new singular term, concept, or framework that could allow us to be done once and for all with the past (again this desire for singularity is at the heart of the Western mode of being). There is no need for a final truth, answer, or method (and certainly not for an agreement). This is not a call for a new purity (NO ART! NO CULTURE! NO NATURE!). Such a call would be to still heed what is at the heart of the Western framework: the desire for purity and dissociation at all costs (paradoxically, this procedure is what keeps so many in the art world—from activists to expressionists—it offers a “pure” realm). We need an adventure that bypasses the triumph of the correct answer. The triumph of suspicion. Being modest: let us keep our attachments and work with them—to experimentally turn, mutate, and reconnect them away from the pull of the Western mode of being. Let’s stay pragmatic in all of this. We start where we are. It is not a big deal, and there is no shame in (still) being an “artist.” It’s just where things have lead. It would be more in keeping with the adventurous spirit of experimenting with attachments to ask: what it can do? What can it connect with? — and not “what is it?” And to see these attachments as stretching far beyond the human. What new things can art do that take us beyond art?

- Move on: Grand Arts’s closing is not the model of a clean break. It is the complex model of moving on—of continuing. Our reality does not give us some form of ideal situation to call a beginning. We need to act without consensus or universal good will, and most importantly without the belief in a clean break.[45] Compromise and negotiation should not sound like new forms of drudgery—these experiments of composing-with are experiments in a contagious, affective joy (look at Grand Arts to see this in action). And to get into that we need to enquire about procedures:

- Develop Cosmological Procedures that can allow us to evolve new modes of being-of-a-world. We are co-composed and co-composing with the totality of our environments—this is procedural. Our current mode of being-of-a-world is procedural—it is just that it is a procedure to make us act as if we were not in and of the world.[47] We have to understand both how we are as the outcome of procedures and how genuinely new ones could be developed.[48]

- Aesthetics: Let us (re)claim aesthetics as being categorically distinct from, and irreducible to, art. Aesthetics is initially a question of sensing, feeling, and being (of/with other forces in emergence). By changing our entangled and embodied sensing and feeling, we allow genuinely new forms of the sensible, seeable, communicateable, doable, and knowable to emerge.[49] Developing a new mode of being-of-a-world (cosmology) and developing a world is not initially a question of developing new ideas or concepts—it is an aesthetic practice.

The development of new forms of aesthetics asks us to rethink perception: unlike the claims of the Western mode of being, perception neither separates us from the world nor works via re-presentation.[50] Our embodied sensing (engaged moving in an environment) leads to perception.[51] New perceptions are always to be co-formed and not simply “found” by looking harder or in new places. These forms are not because of human actions alone—we feel, act, perceive, and know because of much beyond the human (today, for example, we know that our bacterial micro-biota strongly shape our emotional and cognitive lives). Our sensorium is entangled in feedback loops that extend far beyond the human—thus the realm of aesthetics is far larger than us, and not simply an internal mental property. Additionally perception/sensing is distributed across all life, and beyond (non-organic life) in systems and ecosystems. Aesthetics is not just our concern—other beings and systems have aesthetic concerns separate from ours).

Aesthetics in this way precedes the ethical and the political. But the development of a novel sensorium cannot be fully separated from the political. New aesthetic emergences will always have political implications at the embodied systemic structural level. It is a multi-species entangled aesthetico-political cosmological adventure that we need to champion.[52]

- Co-compose (with Bio-Geo-Socio): Perhaps the great realization to take from art is that composition is the most critical and creative act. We need to extend this realization outside the logics of art. Everything is a process of creative composition, from facts to bodies to ecosystems. Each of these is an act of complex Biological + Geological + Social composition. Our key aesthetic and political question is how to compose the bio-geo-socio.[53] A good way to think about composing is that in making something we are not composing a static thing—we are co-composing a process to stably transform an ongoing emergent event (an “individuation”).[54] This process of individuation happens at (and across) all scales —a city, a person, an idea, a political movement, an environment, or a species are all composed and stabilized bio-geo-social individuations. It is important to recognize that this process of composition is a multi-species one.[55] We need to develop new forms of communicating across species and systems.[56] There is a real need for ambassadors for networks, collectives, mediators, species, and alternative cosmologies. In this diplomatic action we need to move from counting on Nature + Culture or the Ideal to have an answer and serve as the final arbitrator (the universal rules of composition that we just need to uncover) to experimentally co-composing with all that exists to form new collectives.[57]

- Emergence: How does something genuinely new come about—how does something seemingly come about from “nothing”? The Western mode of being has always solved this paradox by positing one form or another of an “un-moved mover” (god, ideals, fundamental laws, etc.). Quite simply, our cosmology will not allow there to be something “un-grounded.” But, lest we forget, the consequence of such a position is that there can be nothing genuinely new. In the Western mode, we are reduced to “those who belong elsewhere” and “who get it right.” But, this world does contain surprise and genuine novelty. One plus one is not always two. The genuinely new emerges relationally from fields and processes, and this emergent relation is a thing in itself, irreducible to its history or component parts. In fact, that which has emerged (process + properties) makes its component parts (a global-to-local influence). Given our reductive thing-centered forms of thinking and making, we so poorly understand that the emergent relation is a distinct thing in itself. We need to develop new research/production models that utilize and assume co-emergence. The focus of making needs to reconceptualize creativity as the basic process of reality (away from reducing it to “thing” —a human mental property). Creativity is the possibility that this becoming has the possibility of becoming something genuinely new (emergence). Understanding emergence is critical to develop new forms of institutions.

- Ecological Institution Building: Processes of sensing, individuation, and emergence do not happen in a vacuum; physical structures and tools need to be developed that can support these new cosmological endeavors. Our current structures (from funding to building) work to stabilize and return to neutral the logics of Nature/Culture, Fact/Value, and Subject/Object. Pouring new wine into old bottles is the most certain recipe to keep our failed metaphysics of art going. We need to evolve new forms of institutions:[58] new architectures, new structural procedures, tools, techniques, and concepts.[59] It is about building something different on multiple scales from how to sit to an urban ecosystem.[60] And critical to such forms of building is building in processes of change, evolution and development—embedded institutions that evolve with the question and their entangled communities.

- Craft skills: Before art became a discipline; it was the word we used to denote a skill. We can hear echos of this use of the word when we say things like: “There is a real art to changing diapers.” It is no small understatement to say that there is a real art to doing anything well. We also, at one time, called this The ability to make things well—an art and a craft. Coming after art is a moment to again embrace the craftiness—the skill of being artful in crafting things. Making. If what we can take from art is the focus on composition, then perhaps what we can take from Craft is the focus on, and a care for, the agency of materials.[61] Could we rethink the artisan and matter: co-moving systems to the edge of self-organization— following matter’s expressive relational potential? Perhaps this is a way to engage the bio/geo/social/techno logic of compositions? Multiple arts for new modes of living (worldmaking).

- I like that—a trajectory feels like a direction, a heading, an exploration, and not a commandment (end art now!) . . .

Afterword:

Before X

With multiple X’s becoming (________ )

We start where we are—at some point in our co-evolution with new collaborators and systems, I believe we will pause and look around at what we are up to, and it will no longer be something that makes sense as described by the Western mode of being-of-a-world. We will have gone elsewhere. Why get pulled back into the logics, circulations, systems, and institutions of art? Why not keep going? Once one has climbed up a ladder, why would one keep carrying it around? Perhaps, as has been suggested before, we leave it where we found it.

Why not try—as Grand arts has shown is possible—to put down the ladder?

[1] Marshall McLuhan (1967). The Medium is the Massage.

[2] This concept has been called so many things: Western metaphysics, our base paradigm, a dispositif, an episteme, the Western mindset or framework, and so forth. None is, I feel, quite right: being too focused on the mental, or turning into a discrete thing (it is not something “in addition to”— it is both a set of practices and the outcome of these practices). I would argue that the term needs to articulate that this modality is more than just ideas, habits, or objects— it is all too easy to privilege thinking and the realm of ideas to the detriment of engaging with entangled material practices. Doing and thinking are not discrete. Concepts and ideas do not come first—they only emerge amid an ongoing practice. It is also easy to over-emphasize the conscious or mental aspect of all of this. These patterns and habits are, for the most part, implicit, unconscious, and embodied directly in tools, institutions, and environments. It is our mode of sensing, feeling, doing, and making that involves a wide range of entrained forces, ecologies, species, and even climates. The phrase “the contemporary Western mode of being-of-a-world.” is an attempt to give a name to this emergent assemblage.

[3] This is as good a place as any to say more about art: 1.Art is an historical practice, it has a beginning:13th–16th-century Europe. 2.Art, contrary to what is widely claimed, is not some fundamental aspect of all human nature (or human expression, creativity, universal symbolism, etc.). The simple problem with this argument is that we cannot find any culturally self-identified practices that would fit these definitions or even usage of the term prior to the Middle Ages in Europe, or in any other culture (the anthropological literature on this subject is now overwhelming). Of course, historically speaking, we find cultures doing things that we could loosely define as painting or sculpting all over the world, but they always turn out to be doing categorically distinct things (from art), it is simply anachronistic to call this art. Making art a universal catchall term does a great disservice to these radically different human practices and modes of being-of-a-world. Although length prevents this essay from exploring all aspects of this issue, for those interested in further explication, two useful studies are: Hans Belting, Likeness and Presence: A History of the Image before the Era of Art, and Marshall Sahlins The Western Illusion of Human Nature.

[4] Donella H. Meadows. Thinking in Systems: A Primer, ed. Diana Wright (White River Junction, VT: Chelsea Green Publishing, 2008). Note: Meadows is using this quote from Robert Pirsig as the epigraph to her book.

[5] Additionally, we cannot ignore art’s massive unsustainable debt-centric model of producing ever more deskilled laborers as artist today in BFA+MFA+PHD production line.

[6] Of course the twentieth century is full of critiques of Western metaphysics. Deconstruction and similar forms of critique base their critical stance on the need to overcome all forms of metaphysics. What I wish to argue for is a renewed interest in the composition of alternative metaphysics. art has incorporated many of Deconstruction’s critiques into its methodologies (especially in Institutional Critique and its variants). But what has never been fully at stake in all of these critical enterprises is the very institution of art itself, and the creative/speculative metaphysical act of moving on.

[7] For the sake of expediency, I am necessarily ignoring the actualities of the complex historical evolution of this mode of being and simply presenting it as a contemporary given. It did not evolve all at once, nor did each component evolve simultaneously, nor is it ultimately that old in its current mode (Culture is after all a development of the last one hundred and fifty years). The work of Michel Foucault, Philippe Descola, and Geoffrey Lloyd offers a good introduction to the historical development of this framework.

[8] Often this divide is also referred to as “the one and the many,” or “the transcendent and the immanent.”

[9] Truth, here defined as “unconditioned,” means that the true is true in all times and places, and thus cannot be of the material realm. We see this striving to connect in our desire to find the essence of human nature or reality, or in digging below the surface of things to get at the core, underlying truth beyond mere matter. Ironically, this model of striving for the dematerialized essence of truth translates into many seemingly disconnected material practices: gene essentialism, “It’s the economy, stupid,” evolutionary psychology, and so on— which all have this immaterial essence structure (see Onion Model, below).

[10] At the end of this essay, I begin a list of possible alternative metaphysical/cosmological practices.

[11] “Impressions” are also termed “interpretations,” “sensations,” or “cultural constructs.”

[12] It is important to note that although these concepts have been heavily debated, these debates in fact preserve these dichotomies: “Everything is a social construct”; “There is no really real”; “We are just an expression of our genes”; or “There is nothing beyond matter.” Each of these arguments preserves the dichotomy but tries to swing the needle all the way over to one side. These concepts are inextricably linked pairs: to say “Nature” is to also say “Culture.” The point here is not to take sides within this model but to reflect on the consequences of such a model in totality, and to imagine how we might creatively move beyond it.

[13] See the work of Michel Marder, for example.

[14] This duality of subjectivity versus objectivity is something art celebrates in a number of manners—both in criticism and praise: the focus on individual expression, unique points of view, reality as a social construct, impressions, art as social practice, etc.

[15] This binary, has come under trenchant critique from Hilary Putnam , Isabelle Stengers, and Karen Barad among many, many others. Facts and values co-emerge.

[16] A large swath of art from the sixties, on, has tried to retrofit the importance of events and the relational logic of reality into the art world in an awkward procrustean dance of spectacle and binary reinforcement.

[17] Philippe Descola has done brilliant work to elucidate how this framework, or cosmology as he calls it, is only one of four basic human cosmological frameworks. The others he terms as: Animism, Totemism, and Analogism. Take a look at: Beyond Nature and Culture.

[18] How can I claim to talk about “art” when in a reality there is such a broad diversity of art worlds? I would challenge you to pick up most any contemporary art–related survey book (from Living as Form: Socially Engaged Art from 1991-2011 to Art Since 1900 to the Visual Studies Reader, or even To Life: Eco-Art in Pursuit of a Sustainable Planet) and see where they really differ from this model. They are all implicitly or explicitly utilizing this mode. Even as there is talk of developing new cosmologies these new cosmologies are almost always framed within, through, and for the existing structures of the art world (and it’s deeply problematic systemic metaphysics).

[19] The forays to have a dialog between the arts and the sciences is only a re-enforcing of this divide. Dialog and bridges are careful building and maintaining exercises of categories and institutions. What is needed are procedures that negotiate the co-transformation of all of these practices.

[20] A much-abbreviated list focused exclusively on contemporary thinkers would include Karen Barad, Donna Haraway, Isabelle Stengers, Erin Manning, Evan Thompson, and John Protevi. Further footnotes continue this list.

[21] But this sounds far fetched—so much of what makes up contemporary art is challenging these very ideas of separation and exclusivity? The importance is not just what is said or what is done, but how it is done. The medium is very much the message. I return to this in some detail at the end of this essay.

[22] These solutions, as all solutions in a binary systems must, fall into three basic forms: 1.art is all one Category (take your pick—all Nature or all Culture or all Ideas); 2.art is always both; or 3.art is fundamentally undecidable—and thus we live in the in-between.

[23] This ability to circulate across the dualities is what then allows the great museums of the world to collect all “cultural objects” —and ultimately all objects as finally and truly works of art.

[24] There have been numerous powerful critiques of all aspects of these dualities. I will only mention a few contemporary ones by topic: Nature vs Nurture: Susan Oyama, The fact value distinction: Hilary Putnam, the Mind Body problem: Evan Thompson, The Unconstructed vs constructed nature of facts: Bruno Latour, The passivity of things: Isabelle Stengers, The limits of Representation: Karen Barad, Perception as separate from reality: Alva Noe, Culture: John Protevi, Western nature as a fundamental ontology: Philippe Descola, and Universal Laws: Nancy Cartwright.

[25] It is not so much an issue of being “wrong” in the Classical objectivist sense of the term. The issue is what form of reality—what mode of being-of-a-world—these practices afford us. More than a question of (simply) getting it “right,” it is an aesthetic + ethical issue—what mode of being-of-a-world can we develop? Is it prudent to continue with our current mode of being? This question calls for new forms of invention and creativity (rather than the actions inherent to a model of “getting it right”—changing to fit, etc.).

[26] Fast: Five Years at Grand Arts, Roberta Lord. 2000. Grand Arts Catalog Essay.

[27] The shop was astonishing—fully equipped to make anything and work with any material—metal, glass, clay, wood, etc. During SPURSE’S project, the shop was run by master builder April Pugh and whiz of all media, EJ Holland.

[28] They had an exceptional team of researchers, fabricators, and assistants that had the skills to do pretty much anything—if they didn’t know, they would make it happen by all other means possible.

[29] Obviously, in practice, things were never so neat or clear cut. Nor was Grand Arts alone in developing such a model of practice—it is, as we would expect, quite wide spread.

[30] Because of this model, Grand Arts did not need a public—and in a real sense, the immediate public did not need them (the work was destined for non-local gallery circulations).

[31] When Greek (more specifically Platonic) concepts influenced the writing of Jewish origin stories in the second century BCE, this model transformed into a procedure that inflected all of Western thinking. It is a complex story of how Genesis came to be written, but the cursory version is that under the influence of Greek ideas, Jewish thinkers came to see that they needed to have a more originary explanation for the formation of all reality (Genesis as the product of origin envy or origin anxiety). See John Van Seters (1992) Prologue to History: The Yahwist As Historian in Genesis.

[32] Now, we can also understand this procedure very abstractly and avoid the anthropomorphic god (this is, after all, how science frames its arguments: laws lead to ideas (hypotheses), which are then tested, etc.). We can even transpose this into matter—genes and the idea of the selfish gene is the obvious example. Or, as is the case with art: A creator, removed from the world (the windowless studio) develops and sketches the idea. This gives us the paradigmatic example of the ur maker—the architect. Here the artist draws a model and makes a plan that is meant to be literally the transposed vision of the ideal.

[33] Today we talk about information in these terms: something pure and immaterial (a type of code that can inhabit any necessary substrate— — think of our two great contemporary Platonists: Ray Kurzweil, busy charging his pony at the windmill of the downloadable mind, and James Gleick, James Gleick with his new god: “We are creatures of the information”). Perplexingly our Neo-Platonists have no sense that they are simply the latest versions of an already refuted very old snake-oil, but no matter.

[34] This is pretty much the story of the artist/creator struggling against the world to realize her or his vision, which whereas the overt heroic language has diminished, and the artist is no longer necessarily singular, the process as a whole remains very much our default mode of creation.

[35] To be clear, I would argue that even the early projects at Grand Arts are already moving in this direction. One beautiful example: Mel Chin and GALA Committee were working on injecting complex works of art into the background environment of the TV series Melrose Place (The project was: In the Name of the Place). I am not interested in presenting a “before 2004” and “after 2004” dichotomy. Nor am I claiming that it was any one curator’s vision (they are more than anything an amazing team). That said, the year 2004 pragmatically marks a shift in the direction of Grand Arts.

[36] I should be clear about this term research creation—this was never a term explicitly used by Grand Arts to refer to what they were up to—I’m just adding it to the mix from my observations and discussions in and around Grand Arts at this time. From our personal experience (as SPURSE), I can say that our first conversation with Grand Arts (circa 2007) went something like this:

GA: Hi, this is Grand Arts, you don’t know us but we would like you to do something with us.

SPURSE: Wonderful, but what does that mean because we really take a long time developing projects?

GA: Well, that is what interests us, we would like to support your research in an open-ended manner. It does not have to become anything in a gallery, or that we would understand as art…

SPURSE: Excellent, when can we start?

GA: Now.

[37] It should also be noted that Grand Arts never moved in just one direction. Research creation was always but one of many simultaneous directions. And it goes without saying: these kinds of projects were happening all over, not just at Grand Arts. I think the difference is that Grand Arts took on the consequences of these practices as a structural question (even if it were one that it could never fully address).

[38] Of course the programming changes on something like a monthly basis, and the general trajectory of an institution will evolve (within carefully proscribed limits).

[39] Its neutral—not some “true” universal neutrality.

[40] One telling example: When you are no longer bringing in gallery artists but various forms of researchers, the economic model of not paying artists becomes ethically unsustainable.

[41] While many factors contributed to the closing of Grand Arts, three stand out as critical:

- Attachments cannot be ignored—they produce mutual dependencies. We become obligated not simply by pre-existing others but by what emerges through mutually composed situations. The situation transforms us from the middle via feedback loops across scales and networks.

- The structural limits of institutions that cannot transform—research involves a co-evolving at structural levels with the endeavor. That co-evolution will reach a point at which the transformation is a transformation in kind and not just degree. It takes a very unique logic to allow an institution to cross such thresholds.

- When the funding model allows for independence from any actual community, dependency, or responsibility—community and institution are structurally de-coupled in a manner that promotes a strongly delimited sense of engagement.

Given the above, perhaps it would be more accurate to say that Grand Arts had already closed when it let the first attachment happen—many years before this moment of the official closing.

[42] Ontologies, if you will. Cosmologies captures the sense that these are lived, felt, built, experiential realities—physical worlds and ecologies, and not simply conceptual understandings.

[44] See final diagram at end of essay.

[45] A simple way to begin this: we could engage in practices without referencing art—a movie, or a drawing, or music—what matters is: What do they connect to? What do they activate? What can they do? How can they entangle into and across systems, species, and environments?

[46] Procedures: everything emerges through a process. That these processes have a repeatable logic such that perspectives, subjectivities, and realities stabilize, we can say that these processes are procedural. Procedures entrain a wide swath of forces into stably patterned existence. Note: I am taking my cue for how to activate this term from the work of Arakawa and Madeline Gins.

[47] Look elsewhere: There are astonishing new cosmologies and institutions emerging (as well as powerful anthropologies of other cosmologies, e.g., Descola). Examples: Nunavut and IsumaTV.

[48] Examples: The SenseLab (Montreal) and Madeline Gins’s most recent work.

[49] This procedural idea of aesthetics is in dialog with William James, Ecological Psychology (the Gibsons), the enactive approach (often called 4EA), Foucault/Deleuze’s ideas of a dispositif, as well as recent biological thought on emergent systems.

[50] See the work of Alva Noe.

[51] This is where we need to pay close attention to feminist, queer, and other analyses of the specificity of modes of actual embodiment, as far too much of the current writing on embodiment assumes a neutral, universal subject.

[52] A last question: how does sensing lead to new cosmologies? A hypothesis: feel without connecting. If aesthetics is about what can be felt, it will always exceed and precede cognition (the self-reporting to the self on what it feels). This feeling without connecting can have an effect (affect), and as such it is a meaning-making act—

it is meaningful. We can begin in the feel of the world without having a knowing/sensing experience of this event. This is an experimental inflection point of emergence and composition (A. N. Whitehead, and process philosophy in general have much to add to these experiments).

[53] In some manner this means realizing that the bio-geo-social are themselves carefully composed cosmologies. And that we might look elsewhere to get a sense of very different ways to conceptualize place: indigenous communities worldwide, NGOs such as North Atlantic Marine Alliance (NAMA), and writers such as Ursula LeGuin, Eduardo Kohn, Donna Haraway are all good starting places.

[54] Gilbert Simondon develops a far-reaching pragmatics of individuation.

[55] Think of how many species make up “our” bodies, and even each cell (and the long compositional process of endo-symbiosis); see: Lynn Margulis.

[56] Example: The Land Institute

[57] Some possible starting points to focus on: entanglements and middles; defining things into processes and procedures; co-composition; and developing relays across fields—entanglements into emergent systems.

[58] Some bad news for those who need to keep things neat: it’s going to require more hyphens (for a while at least). These new forms of institution building ask of us to get trans-disciplinary. To join, link, enter, and move across multiple, incongruous fields toward emerging otherwise. But being trans-disciplinary is not an end in itself. It is best thought of as a stage toward developing new practices and cosmologies that are outside of our current mode of being.

[59] Developmental systems theory, in all its glorious forms, has much to offer (Susan Oyama et al).

[60] Example: Arakawa + Gins and The Land Institute.

[61] But the call to craft skills should not be taken as a call to elevate “Craft” in the longstanding debate between art and craft. That idea of the discipline called craft is born of the same logic as art. In coming after, we are also coming after Craft (the binary of the useful vs useless).

SPURSE is a creative design consultancy that focuses on social, ecological and ethical transformation. SPURSE works to empower communities, institutions, infrastructures, and ecologies with tools and adaptive solutions for system-wide change. Drawing upon diverse backgrounds that span the fields of science, art, and design, they utilize unique immersive methods to co-produce new ecologies, urban environments, public art, experimental visioning, strategic development, alternative educational models, and expanded configurations of the commons.