Sally Metzler

It is almost impossible today to go anywhere in the urban environment and not be confronted with a flat panel screen emitting video and audio. They are nearly ubiquitous. Although you might turn off the television when you leave the privacy of your home, media distractions do not cease as you cross the border between personal and public space. Step into a skyscraper elevator and rather than a brief respite from the cacophony of the street, you will likely be faced with an active small screen. Regardless of your preference, you are forced to watch and listen to the news, weather, or the state of the financial markets. You can alleviate the interruption, yet contribute to the disruption, by snuggly affixing your iPod earphones and maintaining the volume at a level so that everyone hears your not-so-private concert—to the agitation of those around you. The active screen so prevalent now in elevators has also migrated to hotel lobbies, clothing stores, taxis, and even bus stops have all joined the club of perpetual information download.

This information, however, is rarely new and certainly not “breaking news” as the streaming ticker on the bottom of the screen insinuates. And more often than not, this mental and visual noise will be a repeat, a rewind of what you have already witnessed. What quantity of CNN footage is actually new within a given hour? The same stories and images are hammered into our mental consciousness at least every fifteen minutes. On a “slow” news day, or even a “fast” one, if you turn on CNN you will become an expert in the current events of the hour. Within a half an hour or so, the same narrative is usually, if not always, repeated. I am an eyewitness to this barrage of repetition, as my gym features two large plasma screens—both impossible to ignore and to change the channels—which broadcast CNN and ESPN. These repetitive images and messages that can mesmerize and equally opiate have impacted the creative and reflective forces of our technologically advanced society. As French philosopher Georges Duhamel in the 1930s appropriately put it, “I can no longer think what I want to think. My thoughts have been replaced by moving images.”[1] Of course, Duhamel was speaking of early film, rather than ubiquitous plasma screens. Nevertheless, his lambaste applies equally to the subsequent generations of video communication.

One should not single out CNN and ESPN as the only examples of repetition and rewind of visual media–although their 24/7 methodology of information download positions them in an unmatched arena. The local one-hour news broadcast in any major city, usually presented on three different stations, will feature the identical sequence of news and stories particularly in the first ten minutes. Even the commercial breaks seem to arise simultaneously. This repetition and sameness are mind-numbing and puzzling, as they have become acceptable and even preferred modes of information transmission through our present vehicles of communication technology, principally the flat panel screen.

In the public sector, the flat panel screen is no longer only a staple of gyms and sports bars, as many restaurants now feature a plasma screen ablaze and pulsating with some form of attention-grabbing programming. One of my favorite sushi establishments runs non-stop Japanese cooking shows on a large screen over the bar. The screen is visible from several of the dining tables as well as the street. Albeit a reprieve from news, it is not a choice to acknowledge the screen and the culinary adventures depicted. Again, the repetition is almost anesthetizing, as well as the interruption into the activity one set out upon initially, in this case to enjoy a nice evening out dining. The screen and video are there, demanding attention and disrupting your thought process whether you wish or not. Does this signal the demise of penetrating conversation between individuals? Surely, it is a challenge to ignore the television or video screen in front of you and pay attention to what your dinner companion is saying. As touched upon earlier, even taxis have embraced the flat screen. Step inside a taxi, and rather than a greeting solely by your driver, the local news or weather will demand your attention, fragmenting your thoughts. This ambush of the flat screen allows scant time for reflection and contemplation. These intrusions into our internal consciousness and concomitantly to the natural flow of creativity are a challenge as we move forward with the burgeoning expansion and availability of new technologies.

Rewinding and repetition as a means of visual communication are not modern constructs. In the Renaissance, copying another painting that was admired was never dismissed as merely a copy nor deemed plagiarism. The derision with which we now associate copies is a contemporary attitude. Young and inexperienced artists were encouraged to copy the masters, to rewind past aesthetic values in order to take the next leap of artistic and aesthetic progress. One looked back to look forward. The advent of reproductive engraving is indeed a form of rewind. When an object or composition was coveted, everyone wanted to possess it, thus the new technology of reproductive engraving and printing made multiplicity of a design a reality. Rewinding was and is a form of egalitarianism in that a work of art or the image per se, could exist in multiples, affording the masses the luxury of possessing what was originally a singular, unique work reserved for the privileged one. Indeed, as Walter Benjamin wrote in his The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, the repetition of a work of art eliminates the intrinsic aura, whereby the uniqueness of the object may be lost.[2] However, the adoration of the original was not diminished; conversely, duplication often enhanced veneration. Albrecht Dürer was no less admired when multiple copies of one of his singular compositions appeared, for example his Knight, Death and Devil or St. Jerome in his Study. Whether producing a woodcut or engraving, this new technology of reproduction allowed a rewind of the subject, style, and design for as many collectors as the incised metal plate or woodblock would allow.

Although less powerful in quantity with regard to multiplicity, painters made second and third versions of their own popular compositions. Artists also created copies of the work of another artist as homage. The best recent example of the admired copy or rewound style is the painting thought for years to be by Leonardo da Vinci, then subsumed by most critics into the after Leonardo or copy, yet in spite of its spurious pedigree, sold for $1.5 million in January 2010. The painting, titled La Belle Ferronnière, is a portrait putatively of Lucrezia Crivelli, mistress of Ludovico Sforza, Duke of Milan. In the early twentieth century, it was purchased as an authentic Leonardo and later given to the buyer’s granddaughter as a wedding present. When the owners tried to sell it the Kansas City Art Institute, experts deemed it a copy, or even worse, a “fake.” The outraged owners, who claimed the painting had been authenticated by an expert in France while they were residing there, instigated a legal battle, suing one of the experts, the famous art dealer Duveen, for slander. The outspoken Duveen had gone on record with a London reporter that La Belle Ferronnière was a copy after Leonardo’s original in the Louvre. The portrait, although now recognized universally as a copy, albeit one dating before 1750, commanded a large sum, in fact three times the auction house estimate of $300,000-$500,000. For many works of art, such controversy and final verdict of a fake would have been the death knell as far as marketability. Yet, this painting is coveted. The new owners, anonymous at this point in time, possess a piece of Leonardo and of his artistic past in some respect.

This issue of Drain explores the concept of rewind. But what does rewind actually mean? Looking up various definitions, it often refers to film or reels, whereby the simplistic notion of going back to the beginning equals success. However, the argument is obfuscated by the question of where are the lines of demarcation between these polarities of alpha and omega? To codify precision of beginning and ending, the concept of time must be critiqued, and in many respects, this is merely a superficial means of organizing our lives.

Aside from the tradition of multiplicity and repetition, rewind is on occasion a celebration of excellence or a longing for nostalgia and values past. This can lead to a renewal when the past is transformed to something new, such in the examples of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and the Nazarenes, who used their veneration for Raphael and the Renaissance masters towards a new artistic expression in the nineteenth century. Even more innovative was the Baroque Gothic architecture of Czech Jan Santini Aichel (1677-1723). He created a novel visual vocabulary by fusing Gothic symbols and Baroque exuberance. The pilgrimage church of St. John Nepomuk in Žd’ár nad Sázavou features a whimsical ground plan in the form of a star and gothic-arch-shaped windows that symbolize the shape of Nepomuk’s tongue, the relic of which is encased in glass on the ceiling of the church, memorializing his martyrdom of having his tongue ripped out and his body thrown into the Vltava River. According to legend, five stars appeared miraculously above the point in the River where his body was cast, hence the star ground plan of the church. Although fairly obscure and not easily visited, Santini Aichel’s church is a masterpiece of architecture—an icon of intellectual and creative rewind.

Today, we celebrate and despise the notion of rewind. Although society generally respects originality, concomitantly there is often suspicion, and even anxiety when facing the new or unfamiliar. Rewind is in many ways about the familiar. It makes one comfortable, validating self-worth and intellectual status. Rewind manifests in myriad situations. There is the phenomenon of museum exhibitions employing a subtle message of rewind to ensure trust among the public. When the art featured is known, when the artist is famous and admired, the public will flock to view the exhibition as opposed to a relatively unknown, although equally talented artist. The majority of today’s public knows the art of Leonardo, Caravaggio, and Monet. Most museum directors can be assured that any exhibition featuring these artists will be a blockbuster, and even visitors who may have never set foot before in their museum will buy a ticket. But, conversely, will the public flock to an exhibition by Luini or Solario (in the case of Leonardo da Vinci, these are those most closely aligned with his art), or one of the followers of Caravaggio, say Simon Vouet or Valentin? Unlikely. Several years ago, the Detroit Institute of Art and the Art Institute of Chicago staged an academic show concerning Italian mannerism and the Medici, and gave the exhibition a title that included the name of “Michelangelo,” although there were but three sculptures attributed to him in the show.[3] False advertising on the part of the Detroit and Chicago Art Institutes? Perhaps more the astute acknowledgement that the public would on the whole bypass an exhibition with names such as Giorgio Vasari, and esoteric, art historical jargon-filled terms like mannerism. Furthermore, there is the underlying sentiment and longing to belong to the collective group who are in the know and in tempo with pop culture, thus embracing the familiar and avoiding the new.

Rewind today and solutions for renewal

For centuries, society has encountered rewind in various forms. From Romans making bronze casts of original Greek sculptures, to reproductive engravings, and to nostalgic art movements, there has been cause for celebration of rewind in its invigoration and augmentation of cultural richness. Yet, today, there is a call for caution in rewind, and the need to limit the seemingly degenerative impact on culture by way of plasma screens and in particular their contribution to visual noise. The argument that technology can ruin society is old. Technology has brought a utopia for many. Connecting via email with relatives living continents apart enters the positive category. But, there is often the subsequent stage of technology that brings discord to those who embrace it. For example, once email and the internet became ubiquitous, a less appealing development of spam, scams, and identity theft ensued. Can this onslaught of visual noise, marking a new terminology, be conquered before we reach saturation point? Can we harness the negative effects of this new technology before it also develops the intrusive and often malicious syndrome we have all witnessed on the internet: “trusted sir, please send me your bank account information so that I may deposit my one billion dollars into your account?” There is also the challenge of the availability of technology being slightly ahead of its time, and particularly ahead of its usefulness or beneficence to society. For example, having the know-how to implement sleek plasma screens in skyscraper elevators, but at a crossroads of what to feature and present to the viewer twenty four hours a day. What are the limitations to originality, reflection, and creativity in a society that has in many respects become a 24/7 world? How much repetition can we endure before it drowns us in a mire of sameness?

There has been fascinating research of late into this field of visual noise and repetition, searching for alternatives that utilize present and future flat screen technology, but mitigate its negative effects. Some of the findings–more valuable for pilots, subway operators, and train conductors–are beyond the scope of this essay. Suffice to say that inventors and scientists are making progress in combating fatigue levels and the imminent danger caused by long-term exposure to electronic screens and other forms of visual noise endured by personnel who rely on screens for their operations. With varying degrees, most of the developed world spends a large percentage of waking hours interfacing with machines, and the list of gateways is ever increasing: cell phones, blackberries, televisions, games, PDAs, iPods, iPads, and laptops. The convenience and accessibility inherent in these devices are inviting and seductive. Yet the concomitant consistent visual noise degrades the human machine interface effectiveness. Screens and the associated repetition will not fade from the urban environment both public and private, and will in fact certainly become more frequent, demanding a solution allowing one to experience information and its collaborate imagery in an unobtrusive manner.

A new art form and technology

The plasma screen–sleek, compact, and highly adaptable to various spaces and places–has produced a new frontier for art and media communication within quotidian life. Concomitant with the invention of the plasma screen is the barrage of visual noise and the ceaseless interruptions. Like all new technology, the plasma screen has traversed numerous stages during which the benefits wax and wane, thus demanding reassessment and evaluation. Any new technology proceeds through a metamorphosis of invention, application, purpose, effects, and results. Once the initial purpose of watching broadcast television on the plasma screen was exploited, the next phase transitioned towards functionality outside of television networks, and focused on public media as well as private enjoyment. Some responses were ambient music and ambient video, pioneered by Brian Eno and Jim Bizzocchi respectively. Eno’s work featured music applied to particular visual imagery, harmonized for both ocular and aural success. But, as Eno stipulated, the video “must be as easy to ignore as notice,” and going further, Bizzochi maintains that ambient video play in the “background of our lives.”[4] Ambient music and ambient video have roots in early avant-garde cinema (one only has to think of Andy Warhol’s Sleep) and video art, yet video art was not dependent on the plasma screen for its technology.

A direct response to the invention of plasma screen technology has been the invention of sub-threshold ambient art, and thus a solution to repetition and visual noise. Ambient video art, although pleasant and pleasing, does not address the negative impact of rewinding and interruption of creative and reflective thought process. A key phase of ambient art went one step further, proffering a sub-threshold visual solution. Invented by Douglas Siefken, this technology imbues a high level of artistic sensitivity to combat quotidian visual noise and benefit our environment, thus increasing the salutary effects of plasma screens. Embracing the notion of rewind and exploiting its capacity for renewal, Siefken implements sub-threshold perception of change and movement on the digital screen (see: www.translumen.net). Engaging and constant, his technology rejects interference with our mindful and present consciousness. His technology and art, defined as Translumenization and Stillism respectively, produce a calming, reflective, and creatively stimulating voice for the electronic display. He engages the viewer with a new art movement, that of temporal art that employs the notion of rewind to arrive at a highly aesthetic and salutary effect for the urban environment. This new technology of digital art solves the problem and alleviates the tension described by Walter Benjamin in that of moving images in film—whereby no sooner has the eye grasped a scene than it has already changed. [5] With Stillism, speed of images, and therefore speed of thoughts, are renewed. Rather than normative film video or stream, Stillism allows, if not leads, the mind towards mindfulness.

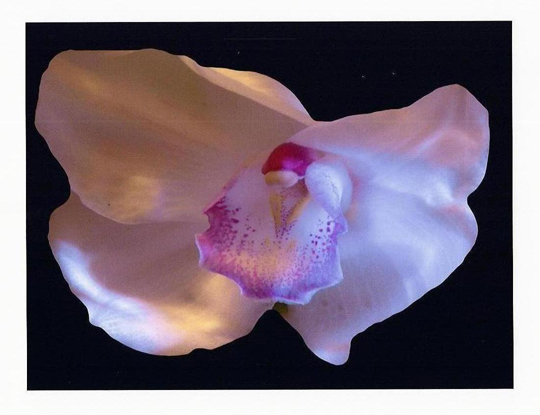

The starting point for Siefken’s innovation is an image, be it a video or photograph. As remarked by ambient video artist Jim Bizzocchi, for even normative slow-motion ambient video, one of the key requirements for ambient art or sub-threshold is the quality of the image and the subsequent manipulation of the image.[6] Although Siefken’s technology can be applied to any form of image, regardless of the author, he also has mastered digital photography, producing images that are seamlessly Translumenized for the flat screen. Such an example is his Orchid and Cityscape series. In the Orchid, Siefken begins with an image that captures the magnificence and elegance of a flower in full bloom. Masterfully framed and conceived, the orchid is the über-orchid (figure 1). Siefken floats the image in a black sea, depicting the enveloping atmosphere with a hyper-acute sensibility. His Orchid is anything but typical. The flower appears as an aerial shot, a bird’s-eye view of the dignity of nature. This simple yet intensely powerful image on the flat screen (or the still image framed) is an aesthetic triumph. Yet, to translumenize the image transports it to another art form and sphere of artistic appreciation (see http://www.flickr.com/photos/siefken/4385196646/). As the spectator observes the seemingly static image of the orchid, at various intervals one will glance again at the orchid and notice the color has changed, the size has altered, and even its position on the screen has shifted. During this passage of time, even if one were to transfix his glance firmly on the screen, the notion of change would be imperceptible. The original image, the starting point of the artistic experience, retains its integrity throughout the performance; the orchid is always there, but will undergo renewal. The sequence of the Orchid is a stochastic fractal, invoking recursion, or the process of repeating the object, in this case the orchid, in a self–similar way. With Transluminization, the iterations and movement are indiscernible, although an alteration in the image has occurred. This temporal art uses sub-threshold extreme gradual change algorithms and patented methodologies (US patents 6,433,839 and 6,580,466) to produce the effect. These dynamic and shifting, yet imperceptibly altered images are displayed with such timing that the eye cannot perceive the differences between adjacent or successive images over at least a five-second interval, yet over more widely disparate time intervals, the images can be noticeably different. The image is rewound while producing nuanced alterations of its original manifestation. The image stream retains the integrity of a still image at any given point in time, but is in fact a continuously evolving image. Aside from the fractal principle of self-similar iteration, translumenization equalizes the alpha and omega. There is neither a true beginning nor end to the series of images, thus creating a cohesive memory. As the digital, temporal art begins with the orchid, changes it throughout time, yet rewinds imperceptibly, arriving at neither the beginning of the orchid nor the end—there is neither boundary nor demands made upon the spectator. The viewer will notice the image on the flat screen, but not be forced to take notice. Most important, the natural flow of mental consciousness remains liberated. There is no narrative to the video and no real end or beginning, thus the viewer is free of searching for closure, meaning, and approach. One now can fully experience the environment strictly according to an individual world-view. Siefken’s solution is prescient. Flat screens will not be going away; they are on the cusp of becoming ubiquitous. Siefken’s art and technology offers the aesthetic and technological triumph of visual noise.

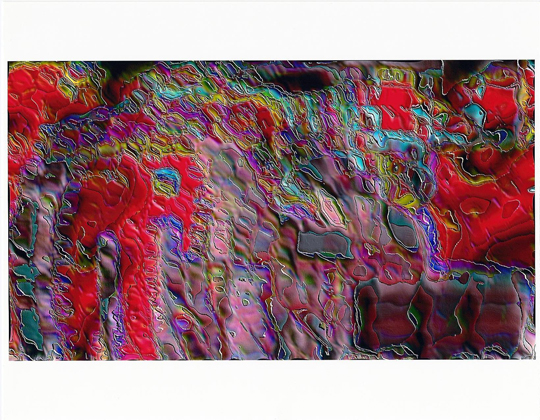

Siefken has created another highly compelling art form called Geo art that implements Stillism. Unlike an image he found, framed, and deftly shot with the digital camera, Geo art is conceptual fantasy. He begins with a geographical muse, be it topography, a transportation system map, or rudimentary terrain of a city. An example is his fascinating interpretation of the Bavarian city of Munich (fig. 2). The image appears as a kaleidoscope of minerals, sand, and other earthly materials. Upon first glance, one might interpret the image as a geological analysis of the city. Yet, it is nothing of the sort: Siefken has digitally transformed the network of the Munich subway system into a labyrinth of brilliant color and mystery. Translumenizing Munich endows the flat screen with an unexpected journey. The shifting patterns of color, although exceedingly nuanced, demonstrate the vibrancy of the city, proclaiming the constant newness of any urban environment.

The Artist and Inventor

As with many pioneers engaged in a new frontier, Siefken’s career genesis represents one of fascinating contrasts. An inventor, engineer, and photographer, perhaps it was inevitable before he conflated his multifarious intellect into one remarkable outcome. At the heart of everything, he has demonstrated that he has mastered technology, yet never sacrificed artistic integrity, and his photographic stills display his aesthetic acumen. But to arrive at such an innovative process entailed a circuitous yet determined road.

By all accounts, Siefken was a prodigy photographer. When other children were still dreaming about what they would grow up and become, Siefken was being paid for his talent. Born in the rural town of Effingham, Illinois, he received his first camera—a Kodak Brownie Holiday Flash—from his parents on his eighth birthday. Anxious to explore this new contraption, he set out with his neighborhood friends, who like most boys spent the afternoon running and jumping or engaged in some form of motion. Knowing little about the mechanics of photography, Siefken started snapping pictures of his friends and their escapades. Finished with the roll, he turned the film in to be printed. Low and behold, much to his disappointment, his efforts of documenting his neighborhood friends produced an entire roll of blur. One should mention that Siefken’s roll of blur occurred long before the digital age, when snapping countless pictures essentially now cost nothing. In 1950s Effingham, every photo counted. After this first unsuccessful endeavor and being a bit precocious and of an intellectual nature, Siefken was determined to understand why his pictures turned out blurry.

Even at the age of eight, he aggressively pursued this dilemma in terms of art and technology. Siefken marched down to the Effingham public library and began reading every book on photography that he could get his hands on. The only ones off limits to him were the “figure studies,” those photography books that included nude photos; for those he finagled adult friends to check the books out for him. A friend four years his senior and who lived two houses down from him in Effingham had a darkroom, and taught Siefken how to develop film. He learned quickly the finer points and mechanics of shooting pictures, as by the time Siefken entered high school, he had a real job as a photographer. In fact, before he even owned a driver’s license, the Effingham Daily News employed him as photographer for the farm edition. His appointment with the newspaper was in addition to his activities for the high school yearbook as well as a freelance photographer for commercials. While working for the Effingham Daily News, Siefken accompanied the assigned reporter to various farms throughout the area, snapping animals, new equipment, and other newsworthy stories important for the agricultural town. He occasionally went along as photographer for crime incidents, capturing the gruesome results of injuries and suicides in the area, often beating the ambulances and police to the scene.

Similar to many young boys, he was intrepid. This exposure to the darker side of life prepared him for his next adventure: joining the Navy, serving in Vietnam, and shooting aerial combat photography. His initial interest in entering the Navy stemmed from a desire to experience life on a ship, partly from the technological aspect. While in Guam, he was able again to pursue his photographic desires. He served in a Navy studio on the island, and part of his activities included the more sedate yet daunting task of shooting portraits of numerous admirals stationed in the Western Pacific. But, at only eighteen years of age, being a photographer suddenly took on a thoroughly different implication, as he was sent to Danang, a city frequently under attack and where Siefken now had the responsibility of combat and intelligence photography. Working out of a mobile lab, he worked against all of the odds, as he maneuvered in the midst of enemy warfare His final aerial assignment in Vietnam, requiring he leap jump from a helicopter, resulted in an injury that sent him out of the military and onto his next career move.

While in Okinawa using high-speed imagery to analyze missile tests, Siefken conceived the idea, yet at that time not the solution, of slow motion video in the extreme. Realizing the need for a movie that did not change to visible eye, Siefken knew this was the goal, but without the invention of a flat panel screen, his plan was ineffectual if not impossible. He never strayed from the idea and importance of the notion of sub-threshold visual perception. Therefore, with the advent of the flat panel screen, he was there on the scene, determined as ever to develop his ideas into a working form.

Siefken’s invention as an art form evolves from the tradition of video and installation art, but unlike its forerunners, it can be both public and private art. The art form called Stillism, is comprised of an image manipulated through technological and artistic means, then transformed into a cerebral and aesthetic viewing experience involving highly nuanced changes in image dimension, color, form, and composition. The technology of capturing the image and arresting its change at an imperceptible level is translumenization. It is important to recognize that although movement weaves throughout the video, visible action or any visual changes must be imperceptible. As an art form, Stillism is a type of video, but until now has been captured under the umbrella term of “ambient video.” Stillism goes much further in its goals and technology. Stillism is an art form that simultaneously engages the viewer and ignores.

Technology has changed our sense perception and attention span throughout the centuries. Keeping pace with these progressions, Siefken’s series of translumenized images rewind and move forward, thereby working with our cognitive and visual powers. His Cityscape series, for example, begins with the Chicago skyline. Changes to the image in the digital loop, perceived at a sub-threshold level, subtract and add simultaneously. He rewinds the image while contemplating the next stage of changes in visual, intellectual and aesthetic values. Siefken’s creation of sub-threshold video art, or Stillism, represents the frontier in the crystallization of the aesthetic and practical applications of technology. This new art form has the potential to transform our everyday environment. Harnessing the explosive and enormous advancements in technology, Stillism seeks to conquer visual noise and implement an art form that is time-based and non-intrusive to our consciousness. It is the future of our visual culture.

Douglas Siefken, Orchid series from Translumenized, video still.

Douglas Siefken, Munich series from Geo Art

[1] George Duhamel, Scenes de la vie future, essays published by Mercure de France 1930. Duhamel was criticizing early film in this statement.

[2] Walter Benjamin published his The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction in 1935.

[3] The exhibition was titled The Medici, Michelangelo, and the art of Late Renaissance Florence, and organized by the Detroit Institute of Arts, the Soprintendenza Speciale per il Polo Museale Fiorentino, and the Opificio delle Pietre Dure of Florence, Italy, with the close collaboration of the The Art Institute of Chicago and the Firenze Mostre, Florence. It first came to Chicago in November 2002, traveling to Detroit in February 2003.

[4] These quotes are from a paper by Jim Bizzochi, “The Aesthetics of the Ambient Video Experience,” presented at the Digital Arts and Culture Conference in Perth, Australia, September 2007. Bizzocchi offers a detailed examination of ambient video’s roots in cinema and early video art.

[5] W. Benjamin, The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.

[6] See Bizzocchi’s paper, section on Creativity and Ambience.

Sally Metzler received her Ph.D. in Art and Archaeology at Princeton University, where she specialized in Renaissance and Baroque art of Central Europe. She has published on the intersections between alchemic philosophy, mannerism, and the Prague court of Rudolf II. Her most recent publication was Theatres of Nature. Dioramas at the Field Museum, a catalogue and history of the natural history dioramas.

Professionally, she has held positions as Research Assistant at the National Gallery of Art, Chief Curator of the Cummer Museum in Jacksonville, FL, and director of the D’Arcy Museum at Loyola University Chicago. She is currently director for KULTURA, inc., an art research firm.