Kevan A. Feshami

Caspar David Friedrich, Rocky Valley (The Tomb of Arminius), circa 1813, Oil on canvas. Public domain.

‘The truest form of prayer is communion with Nature.’[1] Penned by influential white nationalist David Lane, these words capture a deep current of thought within white nationalism’s broader intellect project which emphasizes a critical connection between race and nature. For Lane, communion with a capital-N ‘Nature’ in secluded places far from civilization would reveal its ‘highest law,’ the struggle for racial preservation, while also awakening in white people the strength to successfully fight that struggle. Today, Lane is perhaps best remembered for popularizing the term ‘white genocide’ through the eponymous White Genocide Manifesto. The Manifesto’s concluding ‘14 Words’—’we must secure the existence of our people and a future for white children’—have become a mantra with quasi-religious importance, offering a mission statement for white nationalists around the world. Beyond the 14 Words and the Manifesto, Lane’s writing regularly emphasizes an impending extinction of the white race as a result of a variety of existential threats, ranging from miscegenation to Christian doctrines of human universality, an unrestrained and materialistic capitalism to liberal democracy. Such threats also include environmental destruction; the very nature which could awaken white people to their destiny of struggle and potential victory was under threat from all those forces which imperiled the race. If that nature perished, so too would the white race.

This link between the preservation of nature and both the character and survival of the white race is far from unique to Lane, however. It has a long history in the writings of white nationalists and their antecedents. Nonetheless, Lane’s prominence in contemporary white nationalist discourse, particularly as it concerns racial imperilment, makes him an interesting entry point into the relationship between nature and race in white nationalist thought. Accordingly, this article details some of the history of connections between race and nature in racial nationalist thought, with a particular emphasis on the imperilment of both. It draws on primary material, including monographs, pamphlets, newspapers, and other print material written by white nationalists and their antecedents. Much of this material was gathered through archival research conducted on online repositories as well as at several university libraries in the US. This material reveals a long-standing identification of nature as a site for articulating racial identity and, in particular, for establishing that identity as imperiled by forces which ‘corrupt’ nature and thus the race, as well.

Through this genealogy of Lane’s influences, moreover, we can trace important strands in the development of the relationship between race and nature, following them all the way back to nineteenth-century racial nationalism in Germany. Such analysis offers insights into the complex and multifaceted dimensions of contemporary white nationalism. It also provides a case study in the development of racial nationalism from a narrow focus on ethnic identity to a pan-ethnic white identity. As ethno-racial ideas from Germany began to circulate internationally during and after the Second World War, especially among adherents to Nazism, they offered a foundation for articulating a unified white identity. Nature and environmental preservation played an important role in this process, offering abstract symbols of a shared ‘Nature’ whose laws insisted on the preservation of the white race and the maintenance of its position at the top of a naturally-ordained racial hierarchy.

This history, moreover, is not contained to the immediate postwar period or the late twentieth-century context of Lane and his contemporaries. Today’s white nationalists continue to emphasize a critical relationship between race and nature, often drawing directly on these older lines of thought. The Christchurch shooter, who had a “14” painted on one of his rifles in reference to Lane, wrote of the necessary link between race and nature in his manifesto; so, too, did the El Paso shooter. That link remains crucial for articulating white nationalist identities, particularly through narratives which posit the imperilment of the white race. A better grasp on the development of these ideas provides a window into the intellectual development of a racial and political identity which poses significant challenges to democratic polities and our struggles for a more just and equitable world.

White Nationalism, White Genocide, and David Lane

In the scholarly work produced on the panoply of individuals, groups, and worldviews we might loosely call the ‘organized racist milieu,’ there is a considerable degree of ‘terminological chaos’ compounded by ‘a lack of clear definitions.’[2] One finds a plethora of terms like ‘far right,’ ‘radical right,’ ‘extreme right,’ ‘white supremacist,’ ‘white separatists,’ ‘neo-Nazis,’ ‘fascists,’ and so on, often with competing definitions for each term or simply no definition whatsoever. Compounding this terminological chaos is a significant degree of diversity in outlooks among the constituents of this milieu. We find supremacists alongside separatists who advocate for ‘nationalism for all people.’ Some view an atavistic return to a distant, half-glimpsed past as the only salvation for the white race, while others urge forward thinking to an as-yet unrealized future. Religiously speaking, pagans, Christians of various sorts, atheists, adherents of whiteness as a divinity in itself (in the form of the World Church of the Creator), occultists, ‘Eastern’ mystics, and even Satanists all contend for pride of place as the spiritual viewpoint most appropriate for white people. Such variety only contributes further to the terminological chaos plaguing classificatory attempts in this field. To avoid adding to this confusion, it would be prudent to delineate as clearly as possible what is meant here by the term white nationalism.

White nationalism in this article refers to groups and individuals who adhere to three common conceptions which cut across an otherwise diverse milieu. First, white nationalists have some notion of a unified white race. The race may be referred to as ‘European,’ ‘Aryan,’ or in more mystical terms like ‘Thulean’ or ‘Hyperborean.’ Nonetheless, an idea of a shared racial bond—one which exceeds specific ethno-linguistic nationalities—provides, in the words of Greg Johnson, editor of the white nationalist online magazine Counter Currents, ‘a sense of common origins, common enemies, and a common destiny.’[3] The phrase ‘our people’—or variants like ‘our kin’ or ‘our folk’—are a commonplace in white nationalist discourse, lending a sense of belonging that can provide crucial coherence within an otherwise highly differentiated milieu.

Second, there is a sense that the race has indelible links to specific geographic places or abstract natural spaces which form a critical part of their racial identity. Thus, when notorious US white nationalist Richard Spencer declares that ‘America belongs to white men,’[4] he is invoking this common connection between race and place. These connections between race and place echo the Nazi doctrine of Blut und Boden [blood and soil] which emphasizes a racial connection between a people and ‘their’ land, and itself drew on nineteenth century German racial nationalist attitudes which assert that ‘for each people and each race a countryside…becomes its own peculiar landscape’ (Gmelin).[5] For white nationalists, these spaces are alive, animated by and animating of the race who lives in them. One is essential to the other, and together they form a living whole. The holistic, organic unity they form, moreover, provides the basis for the environmental anxieties among white nationalists which are of concern in this article.

Finally, race, place, and the connection between them are understood as imperiled. There is a sense in white nationalist discourse that the race is on the brink of extinction, that the spirit which animates it and ties it to the land may be soon extinguished. Such discourse also calls for resistance to this perceived extermination, urging adherents to action. It is here that Lane’s writing has been particularly influential. Imprisoned in the mid-1980s for a series of crimes, including murder, committed as a member of the white nationalist terrorist organization The Order, Lane became something of a hero to many white nationalists in the 1990s. As a result, the number fourteen became a commonplace in white nationalist symbolism, invoking the 14 Words and representing defiance to white genocide. In the process, both symbol and mantra’s prominence, they have ‘become a “master frame”’ for white nationalist discourse.[6]

Lane’s writing exemplifies these three categories. He insists that race asserts itself over and above ethnicity and provides a foundation for a pan-ethnic solidarity.[7] Throughout his work, he regularly emphasizes an important relationship between the white race and its land, which makes communion with nature possible. Finally, there does not seem to be a text in Lane’s corpus that fails to mention racial imperilment and white genocide. Anxiety pervades his written work, animating calls for resistance by any means and at any cost. Yet, even with this throughline of racial imperilment and white genocide, Lane’s writing is diverse. There are the familiar saws about miscegenation and anti-Semitic tirades; yet, he also offers a complex numerological system for decoding hidden Aryan messages in the Bible[8] along with denunciations of ‘C.R.A.P.’: ‘Christian Rightwing American Patriots’.[9]

Lane was also an influential factor in spreading Odinism within white nationalist circles, promoting it as a religion which ‘lives in our blood’ and ‘stirs our racial souls’.[10] Together with his wife Katja Lane and friend Ron McVan, Lane founded Wotansvolk—German for Odin’s People—a spiritual ‘path’ meant to introduce white people to their ‘ancestral’ and ‘folkish’ religion. Nature serves an important purpose here: the cover of Creed of Iron, an introductory pamphlet to Wotansvolk, depicts an initiate enacting a ritual under the stars, surrounded by standing stones, runes, and other mystical symbols, engaging in that ‘highest form of prayer’ through communion with nature.[11] According to Lane, through this communion with nature, one can come to understand ‘the majesty and order of the infinite macrocosm’ along with ‘the intricacies of the equally infinite microcosm,’ which together reveal the role each member of the race plays ‘as a link in destiny’s chain.’[12] Nature reveals one’s purpose, one’s role in the turning of the cosmos, thereby demonstrating how one might act in accordance with its ‘Laws,’ the highest of which is ‘the preservation of one’s own race.’[13]

According to this theology, the white race had once been in harmony with nature’s purpose. Writing about Wotanism—a more popular name for Odinism among white nationalists—McVan describes a time before Christianity in which ‘nature mirrored the people and the people mirrored nature, and the two participated in an existence where there was no sharp separation between them.’[14] Such an era came to its end, however. Following the Christianization of Europe and centuries of Church rule, most practitioners of the ancestral religion lost their way, coming to value a supposedly false universality of human life before God, over and above the ‘natural’ perseveration of one’s race.

Separated from Nature, white Aryan people embraced an ‘unnatural’ capitalist materialism, supposedly inflected with Judaism, which ‘ultimately leads to conspicuous, unnecessary consumption, which in turn leads to the rape of Nature and destruction of the environment.’[15] As a result, nature itself has succumbed to environmental degradation. Lane expresses doubt that, under current conditions, the planet can even carry just the current population of white people ‘without further ruining the topsoil, depleting the forests, exhausting the fossil fuels and producing nuclear wastelands.’[16] Without carving out a place for themselves at the expense of other races, while simultaneously ensuring the survival of the ecosystem, white people face extinction. Environmental preservation then is linked with racial preservation, and the fight to stop white genocide becomes also a fight to end environmental degradation and return to a harmonious union with nature.

Influential as he is, Lane is far from the only white nationalist to express similar concerns about nature and its relationship to the race. Indeed, he draws on and speaks to a longstanding tradition of connecting racial identity to the environment. Tracing his influences, we can follow them back to the struggles over German national and racial identity during the nineteenth century. To those roots we now turn.

Ein Volk, ein Wald, ein Land

Caspar David Friedrich, The Chasseur in the Forest, 1814, Oil on canvas. Public domain.

The nineteenth century was a chaotic one for Germany. Wars, occupations, revolutions, along with rapidly changing cultural, political, economic, and demographic circumstances brought tumult and uncertainty to a region that already had little political and less cultural unity. Unification, which arrived only in 1871, brought with it its own challenges, especially as Germany began industrializing at nearly unprecedented speeds. In the chaos, those interested in articulating visions of a united German people sought symbols which would be appropriate to the task of unification. A variety of nationalisms arose, some interested in advancing liberal reforms, others in preserving romanticized visions of a pre-modern past. Even left forces, tied to the newly emerging industrial proletariat, contested the national question. Common to much of this nationalistic discourse was a sense of anxiety, a fear that, without a true and meaningful unification built on common symbols which could elaborate a common culture, Germany and its Germans would simply vanish into history.

Such anxieties did not simply emerge whole cloth from nothing, however. At the start of the nineteenth century, Germany existed under the nominal auspices of the Holy Roman Empire, less a unified country than a loose patchwork of principalities, ecclesiastical estates, free cities, knightly lands, and other minor territorial holdings with varying degrees of autonomy from the Emperor. A complex web of legal agreements bound the hundreds of smaller entities to the Empire; however, the varying degrees of sovereignty and special privileges afforded to each ensured the whole was ‘an ill-cohering, clumsy mass’ (Müller).[17] In the midst of such disunity, a common, shared identity was lacking, and regional peculiarities predominated.

This is not to say that some sense of commonality was entirely absent. In the latter half of the eighteenth century, scholars like Johann Gottfried Herder wrote of a German nation joined by shared language, customs, and culture. During this period, the term Volk, a word meaning ‘people’ or ‘folk,’ also lost its more ‘pejorative’ sense—in that it referred to the ‘lower’ strata of feudal life—’and came to denote the people as a whole, all members of society.’[18] A growing sense of a pan-German identity was emerging during this period, particularly among intellectuals. At the heart of the nationalist turn were the same republican and Enlightenment values which animated the Revolution in neighboring France. The French Revolution initially occasioned support from many German intellectuals, who saw in the French efforts to build a republic according to rational, democratic principles a blueprint for their own dreams for Germany.

German enthusiasm for France was not to last, however. By 1804, Napoleon had crowned himself Emperor, and the more or less constant state of warfare between France and its neighbors, already a source of chaos for the Rhineland, brought turmoil to all of Germany. In 1805, French forces occupied Vienna and decisively defeated the Austrians—the major power of the Holy Roman Empire—at the Battle of Austerlitz. The ensuing peace negotiations, culminating in the Treaty of Pressburg, forced the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire, major territorial concessions to France, and the establishment of the Confederation of the Rhine, a collection of client states in western Germany under the de facto control of the French government. In 1806, Napoleon defeated Prussia, the other major power in Germany, at the Battles of Jena and Auerstedt, prompting the 1807 Treaty of Tilsit which ceded considerable Prussian territory to the French and their allies.

French occupation would be a traumatic experience for much of Germany. In the Confederation of the Rhine, the French set about enacting reforms in line with rational principles. Centuries-old political structures, including a popular Imperial judicial system,[19] were uprooted and replaced, while the aristocracy was stripped of title and privilege. The French army, dependent on foraging for supplies to feed and equip itself, had ravaged the Rhineland for years during the Napoleonic wars, pillaging, looting and contributing to a general state of lawlessness that continued under occupation.[20] Already on a shaky socioeconomic footing, Prussia also suffered greatly under the French. A French army numbering well over 100,000 stripped the countryside, leaving rural Prussians bereft of food and supplies. Starvation and disease became rampant, meaning ‘death rates skyrocketed’: in one city, ‘the weekly number of deaths in August 1807 rose to 230-240—and this from a pre-war figure of 30-40.’[21] While French reforms did bring some benefits to Germany, particularly an end to serfdom in most regions, they nevertheless soured many Germans on Enlightenment principles and ‘touched off an intense struggle between advocates of change and defenders of tradition’ among German nationalists.[22]

These experiences also stoked the fires of nationalist sentiment across Germany. There was a widespread sense that a lack of German unity had contributed to these defeats, especially given that several of the former Empire’s states had actually fought with the French against the Austrians and Prussians. Speaking to these attitudes, the philosopher Johann Gottlieb Fichte gave a series of speeches in 1808, later collected in print as the Addresses to the German Nation. Fichte urged against the regional particularities of the old order, insisting that ‘we must become on the spot what we ought to be in any case, Germans.’[23] Prefiguring Lane, Fichte called for his fellow Germans to understand themselves as a unity, as ‘link[s] in the eternal chain of the life of the spirit’ who are ‘subject to a higher social order,’ namely the nation to which they are a part.[24] Their ‘Germanness’ would be defined by their language, which differentiated them from ‘foreign’ elements like the French, whose liberal reformist attitudes were alien to Germany.

In light of the French occupation, Fichte also defined this Germanness as deeply imperiled. Under the rule of a foreign power with its own language and ideals, the German language risked ‘admixture…and corruption by some alien element that does not belong.’[25] Corruption meant not only loss of the language, but loss of the spirit, unity, and even eternal life of the nation. Bound together in spirit through their language, individual Germans could expect an ‘eternal continuance’ in the life of their nation, an afterlife that would endure so long as the people, the Volk, remained.[26] If the language perished, however, this common spirit and the eternal life it offered would also expire, condemning the nation and its constituents to oblivion. The stakes were, moreover, much higher than just national survival. Fichte endowed the German people with a messianic purpose. Their union would bring about a new, better world which would offer a counterpoint to the corruption of the French. If Germany failed in this task, the outcome would be grim: ‘if you sink, all humanity sinks with you, without hope of future restoration.’[27] Thus, Fichte’s conception of German identity was articulated, from its beginning and in response to the turmoil of French occupation, through a frame of existential anxiety. Germanness was needed to save the nation, but that very Germanness was in a precarious position and could be easily lost.

Fichte’s Addresses were part of a larger turn which developed the earlier nationalism into a sentiment tinged with hostility to foreignness. Echoing these sentiments, Ernst Moritz Arndt, a prominent nationalist intellectual, described Germany in his popular song ‘The German Fatherland’ as a place ‘where fury exterminates foreign trash’ and ‘every Frenchman is called enemy.’[28] Yet, despite the growing popularity of nationalism, liberation from the French failed to deliver a much anticipated unification. Following Napoleon’s defeat during the Wars of Liberation in 1813, the rulers of Germany’s most powerful states met in Vienna the following year to establish the shape of the postwar political order. Interested in preserving their own sovereignty, they established the German Confederation, a loose political arrangement that preserved local autonomy for major states like Prussia and Austria while abandoning any pretense of unification. The arrangement would define political life in Germany for half a century, but ‘no respectable nationalist expressed anything but scorn for the German Confederation.’[29]

Abandoned by most German states, nationalism became a popular project. Artists, poets, scholars, and intellectuals searched for symbols through which to define the German Volk and construct a popular national unity. To this end, nature offered an important symbol of the nation. The concurrent trend of Romanticism had already introduced an emphasis on nature into German intellectual life. During the French occupation, romanticists like the painter Caspar David Friedrich portrayed nature as part of the nation, contributing to its defense against the invaders. Friedrich’s painting The Chasseur in the Forest (1814) depicts a lonely French soldier standing on a forest path, surrounded by imposing trees which tower over him. His arms hang at his sides and his shoulders appear slumped, lending him an air of helplessness and despair. A raven sits on a stump in the foreground, portending the soldier’s death in the wilderness. The German landscape itself was symbolically mobilized in defense of the nation.

Already connected to the nation, the natural landscape of Germany provided an important symbol that transcended the territories of petty princes. National unity could be conceived of in a land shared by all Germans. As such, the word ‘rootedness’ became a commonplace in nationalist discourse, where it evoked ideas of ‘an ancient people set in an equally ancient landscape, which by now bore the centuries-old imprint of the people’s soul.’[30] The connection to the land offered a sense of history to Germanness, embedding it in the environment in which the German people had lived for centuries. But the landscape was not simply a passive receptacle for the German spirit. Wilhelm Heinrich Riehl, a nationalist and journalist, wrote at midcentury that the features of a landscape ‘determine many a subtle, hidden trait in the life of a nation.’[31] The land was itself part of the Volk. It shaped the nation and was an essential aspect of its character.

Among the features of the German landscape that were most integral to the spirit and nature of the Volk was the forest. Given that every region of Germany was forested to a notable extent, and in some regions quite heavily so, ‘sylvan omnipresence’ enabled ‘The Forest,’ as a proper noun, to become ‘a natural symbol of a generalized, unified, and truly national landscape.’[32] For many nationalists, the forest also evoked the wild and free spirit of Germany’s barbaric past. Riehl, in particular, articulated a distinction between the field, which represented Germany’s efforts at civilization, and the forest, which ‘still affords us civilized creatures the idea of a personal freedom.’[33] The forest was a gateway to the ancient and free spirit of the Volk. This is not to say that Riehl advocated a wholesale atavistic primitivism. Rather, like many nationalists, he saw in the forest a critical link to Germany’s past that helped to retain its national character in the face of homogenizing but necessary civilizational development. But Germans needed to be careful that field did not overtake the forest. He warned his readers that:

If you wish to see society reduced to a bland parlor culture, where everything is identical in color and finish, then uproot the forests, level away the mountains, cordon off the sea. We must retain the forest not only to keep our stoves from going cold in wintertime but also to keep the pulse of our national life beating warmly and happily. We need it to keep Germany German.[34]

More than just critical to Germany, the forest, for Riehl and many of his fellow nationalists, was Germany.

The importance of the forest not only provided a means to define the German Volk internally; it also offered a symbol to differentiate Germany from the ‘foreign.’ To that end, the Roman author Tacitus’s Germania, rediscovered in the late fifteenth century, became an important document for German nationalism that helped to define Germans as a distinct people from the rest of Latin Europe. In Romantic overtones, Tacitus emphasized the Germans’ wildness and freedom, comparing them favorably against their more servile and decadent counterparts in the Roman Empire. The key aspect of this freedom was the forested wilderness these ancient Germans were said to inhabit, an analog to which could not be found in Roman Italy. In addition, the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest—a resounding defeat for the Romans which effectively ended their incursions across the Rhine—further linked the forest, which was critical to the victory, to Germanness and to resistance ‘against foreign domination.’[35] To commemorate the moment, German nationalists erected the Hermannsdenkmal, a towering, 175-foot-tall monument completed in 1875. Commissioned by nationalist Ernst von Bandel, the statue memorializes Hermann the Cherusker, who led the Germans against the Romans in the battle. Constructed on a wooded hill in the Teutoburg Forest, the statue, unlike other monuments, ‘is fused with the landscape’ in order to ‘heighten its symbolism.’[36] Here, German history and the forest meet in a unity opposed to the foreign, as Hermann’s upraised sword faces west toward France, offering a warning to Germany’s enemies.

Ernst Von Bandel, Hermannsdenkmal, 1875. Photograph circa 1900. Public domain.

This investment in the natural landscape and the forest as essential components of the German spirit, however, brought with it similar existential anxieties to those expressed by Fichte. As the nineteenth century progressed, Germany’s nascent industrial revolution began to rapidly increase its pace. Coal production, a key indicator of industrial growth, increased twentyfold from midcentury to Unification in 1871, and would nearly quadruple again by the start of the twentieth century.[37] What had been a predominantly rural country, where most Germans lived in small towns and farming villages, was swiftly transforming into an industrial giant. These rapid changes put pressure on traditional modes of life. Germany’s guild system, already flagging since the eighteenth century, fell first into decline and then into obsolescence as mass produced goods displaced the demand for artisanal crafts. Familial structures also buckled under the stress. Land ‘reforms’ intended to spur industrial growth imperiled peasants’ ability to make a living, forcing men to leave home to find extra work, while increasing the already considerable workload expected of women. Alcoholism became a widespread problem, along with ‘a twelve-fold increase in demands for divorce or separation from the late 1700s.’[38]

Industrial development also imperiled the natural landscape in which so much nationalist sentiment was invested. Mining damaged mountains, while industrial demands despoiled forests and polluted rivers. Thomas Lekan details how, in the years following Unification, popular nationalist associations concerned with environmental protection became a significant force in German social life. Called Naturschutz (nature protection) and Heimatschutz (homeland protection) organizations, these groups argued ‘that a highly cultured nation [like Germany] must curb its population’s materialist impulses in order to attain the ideal goal of long-term environmental stewardship.’[39] For many in these groups, environmental degradation imperiled not only the landscape, but the German people themselves as part of that landscape. Again prefiguring Lane, the materialism of industrial capitalism was understood here as a threat to Germany’s natural landscape and thus the spirit of the Volk itself.

Lekan is careful to note that those involved in the environmental protection movement were of diverse political backgrounds. While many of them were nationalists, nationalism in nineteenth century Germany was itself a diverse pursuit, involving liberals, conservatives, socialists, and others. Nevertheless, discourses of national spirit and character unsurprisingly attracted racial, or völkisch, nationalists who saw in the destruction of the environment a corruption of German racial purity, especially at the hands of the Jews. Hermann Löns, a popular völkisch novelist, described environmental preservation as ‘a battle for the preservation of the health of the entire population, a battle for the strength of the nation, for the well-being of the race.’[40]

These links between environmental and racial preservation were a commonplace in völkisch nationalism as the nineteenth century gave way to the twentieth. Guido von List, an Austro-German völkisch nationalist writing in the early 1900s, envisioned nature as a wellspring of racial purity. Something of a self-styled mystic, he promoted an atavistic vision of Wotanism, a romanticized interpretation of pre-Christian German paganism, as the natural religion of the German people in ‘reaction to the modern world of streets, shops, and factories.’[41] Central to this religion was the pre-Christian runic alphabet, whose ‘mysteries’ List explained in 1908’s The Secret of the Runes.

For List, Wotanism offered a path through which the German race might retain their originality and thus their status ‘as a “natural people”’ who are ‘free from any kind of false sophistication,’ like that of modern industrial society.[42] Maintaining a connection to nature was essential for the German race, in that such links enshrined the ‘primal laws of nature’ in racial consciousness, the foremost of which is the preservation of racial purity. Here too we find forest symbolism deployed in the form of ‘the “world-tree” Yggdrasil,’ which provides the frame for the nine worlds of Germano-Scandinavian myth. According to List, Yggdrasil served ‘as the Aryan tribal tree,’ reminding Germans that ‘the tribe, the race, is to be purely preserved; it may not be defiled by the roots of the foreign tree.’[43]

As a natural people, ‘Ario-Germans,’ List’s preferred term for the German people which highlighted their supposed Aryan ancestry, were endowed with a deep love and respect of life itself. They understood that even the most minor entities, ‘minerals [and] plants,’ were endowed with life and were thus an important part of the cosmos[44]—although, it is unclear, and rather doubtful, whether ‘foreign’ peoples like the Jews were appreciated for having this wondrous life force. This ‘desire to live’ and celebrate life stemmed from their ancient ‘religion of light’—including both Wotanism and a second, esoteric Aryan religion called Armanism—which contrasted with ‘the dark Asian-Roman,’ meaning Jewish and Christian, worldview which lacked the same love of life.[45] Subjected to Christianity and, through it, Jewish influences, List believed that the German people had lost their way in the world of industrial modernity and were therefore at risk of losing their naturalness and love of life. Without a return to their ancient religion, Germans risked disaster.

Houston Stewart Chamberlain—an English expatriate and Germanophile who became a leading intellectual in völkisch circles—also writing in the early twentieth century, connected ancient Aryan teachings to a love of life and nature. ‘Among the Indo-Aryans,’ he contends, ‘the fundamental principle is: harmony with nature.’[46] Aryans enjoyed a bond with nature and life that taught them its true value, a bond which was lacking in other religions and people, most notably the Jews. Illustrating this point, Chamberlain recalls an incident when, as a physiology student in Geneva, he encountered a dog who had been subject to vivisection. Hearing the animal cry provoked an intense reaction, and he writes that ‘it was for me a voice of nature, and I cried aloud in sympathy.’[47] Convinced the dog was suffering, Chamberlain was rebuked by his professor who insisted that its spine had been severed and thus it could not feel pain. Yet, Chamberlain insists that he could feel the dog’s suffering on account of a mystical Aryan empathy and sensitivity to life which transcends the bounds of the rational and empirical: ‘My understanding for the suffering of the dog was just as little a logical understanding as an echo in the forest is a syllogism; it was a spontaneous impulse whose depth of understanding depended on the level of my own ability to suffer.’[48] His professor, on the other hand, was incapable of such empathy because, according to Chamberlain, he was Jewish, and thus limited by a racially inherent, materialistic outlook blind to a deeper transcendental, racial idealism.

Like List, Chamberlain also viewed Germany’s rapid industrialization with wariness. This ‘new world, which bursts forth with uncanny haste from all sides’ held the potential to be a ‘heavenly whirlwind’ which might lift the German people to new heights, or it might prove to be ‘a satanic whirlpool which will finally hurl us down into abysses.’[49] To realize the former and avoid the latter, Chamberlain insists in his 1915 book Political Ideals that Germany would need to embrace values steeped in tradition, values that promote aristocratic hierarchy and racial differentiation, which could carry the nation through this period of turmoil and change.[50]

However, the materialistic values of industrial capitalism, laden with Jewish ‘influences,’ threatened to lead Germany astray, particularly in terms of the nation’s relationship to its land. Whereas aristocrats, in Chamberlain’s Romantic estimation, had been duty-bound to care for the land they ‘possessed,’ as well as the people who lived on that land, the new industrial capitalist recognized no such obligation. Awash in money, capitalists simply own land; they share no connection with it and see no value in it beyond the acquisition of more money. Indeed, the capitalist ‘has no land, therefore also no fatherland,’ and thus, without the roots which bind one to land and Volk, ‘he loves unrest, change, catastrophes of every sort.’[51] The destruction of Germany under the weight of industrial modernity was of no concern to the capitalist, and might even be treated as an opportunity for profit.

Chamberlain and List are emblematic of broader themes within völkisch nationalism. An understanding of the race as bound to land and nature predominated and informed beliefs in the connection between natural purity and racial purity. Such attitudes, moreover, contributed to a nascent emphasis on animal rights expressed through vegetarianism and anti-vivisectionism, stances which were perceived to stave off racial degeneration.[52] Speaking to these views, nationalist Cosima Wagner, wife of composer Richard Wagner and Chamberlain’s mother-in-law, asserted that ‘only when we recognize animals as living beings like us can we speak of true religion, namely the bond between ourselves and the whole of Nature.’[53] But these views were also imbued with a sense of imperilment. The German Volk, in the face of a destructive and alien industrial modernity, would have to secure their land, prevent its despoliation, and elevate this love of life to a central value. To do otherwise would risk the contamination and eventual destruction of the racial spirit which animated them.

In the aftermath of the First World War, these racial nationalist interpretations of environmental preservation, relationships to nature, and animal rights found greater purchase in the larger environmental protectionism movement, becoming a key part of its discourse.[54] Important segments of the Nazi party also came to embrace aspects of this thought. List’s pagan worship of nature was looked on favorably by the party and informed some of its most important celebrations.[55] Reichsminister of Food and Agriculture Walther Darré, a longtime völkisch nationalist who had popularized the phrase Blut und Boden, advanced policies to combat the environmental destruction wrought by industrialization—although he was often far from successful in realizing these policy goals in law. Many members of the party, including Hitler, even embraced vegetarianism. Once in government, the Nazis made more concrete gestures toward these values, as well. An animal rights law, which included a ban on vivisection, was passed in 1933, followed in 1935 by ‘the world’s most comprehensive piece of environmental conservation legislation.’[56] Many of these protections would be scaled back or undermined, especially as the war effort demanded increasing sacrifices, leaving open to question the party’s full commitment to environmental and animal rights values. Nevertheless, by making such values a part of their rhetoric, the Nazis ensured that a concern for nature would continue on in the ideas of their adherents following the Second World War, where they would begin to circulate internationally and contribute to a pan-ethnic white nationalism.

Völkisch Environmentalism and Postwar White Nationalism

Following the revelation of the horrors of the Holocaust and other fascist atrocities during the war, the prospects of racial nationalism fell into rapid decline. Mass racist movements like the Ku Klux Klan and the British Union of Fascists, already waning before the war, more or less vanished, particularly in comparison to their prewar heights (the Klan had boasted a membership numbering in the millions during its peak in the 1920s). In Germany, Nazism was outlawed and nationalism of most stripes was looked on with suspicion. This is not to say that racism itself vanished; rather, the ‘effect [of this historical development] was to reduce drastically the “political space” available’ for racial nationalism to act in mainstream politics.[57] Yet, despite this hostile climate, the example of the Nazis and their völkisch forebears still inspired a handful of die-hard adherents to carry on their ideals, including the connection between environment and racial purity. Among these postwar racialists, one of the most interesting, particularly in terms of environmental preservation and race, is the Aryan ‘mystic’ Savitri Devi.

Photograph of Savitri Devi, circa 1937. Public domain.

Born Maximiani Portas in France, Devi was a devoted adherent of Nazism and völkisch nationalism. Keenly interested in völkisch theories on the Aryans and the supposed ancestral home of the white race in the Himalayas, Devi moved to India in order to pursue a deeper understanding of the ‘mysteries’ of the Aryan religion. Drawing on her research into South Asian religious beliefs, Devi crafted a cyclical theological worldview, elaborated in her 1958 book The Lightning and the Sun, out of a union of Hindu cosmology and Nazi race theory whereby a ‘pure’ and ‘noble’ Aryan race would live in a harmonious golden age before declining into catastrophe, only to be reborn again in grace.

Reading this system back into Nazism, Devi claimed that ‘the National Socialist Idea’ urged struggle against cyclical racial decline, and that the Third Reich had been a doomed but noble and heroic fight against the movement of time. National Socialism, Devi argued, ‘ultimately expresses that mysterious and unfailing Wisdom according to which Nature lives and creates: the impersonal Wisdom of the primaeval forest and of the ocean depth.’[58] This ‘Wisdom’ by which Nature ‘creates’ and which is exemplified once again in the forest is, of course, racial hierarchy.[59] Such wisdom is ignored in the modern world, according to Devi, by those whose ‘childish pride in “progress”’ drives a ‘criminal attempt to enslave Nature…in our over-crowded, over-civilized, and technically over-evolved world, at the very end of the Dark Age.’[60] Rather than live in harmony with a racially hierarchical nature, in other words, the proponents of the modern world—industrialists, capitalists, liberals, and Jews—seek to bend that nature to their whim, despoiling the Earth and driving the Aryan race into decline.

Like List and Chamberlain, Devi also wrote extensively about the importance of respecting all life—’racially inferior’ human life notwithstanding—as part of an Aryan racial trait. In 1959’s The Impeachment of Man, Devi criticizes ‘man-centered’ philosophies which place a universal value on human life. For Devi, not only is human life hierarchical, meaning some humans’ lives have no value, but any worldview which elevates the human unjustly ignores the value of non-human animals. A more holistic, ‘life-centered’ philosophy, by contrast, would promote ‘the principle of the rights of animals, and set a beautiful dog above a degenerate man.’[61] Devi’s ‘concern’ for life extended beyond animals, as well. The life of plants, trees in particular, were also to be valued and elevated above ‘degenerate’ human life. Decrying ‘the gradual disappearance of forests all over the surface of our planet,’ she advocated for a significant reduction in industrial production and development in order to preserve Earth’s ‘leafy mantle.’[62]

These efforts to preserve forests and liberate animal life would require a new political order along the lines of ‘Germany’s now persecuted, heroic ruling elite’—the Nazis—who were to be emulated for the value they placed ‘upon the right of animals and trees,’ a likely reference to the Reich’s environmental legislation discussed above.[63] Realizing a life-centered philosophy also necessitated a drastic reduction of the human population down to a minimal fraction of its current level. Devi is not explicit about how this would be done; however, it seems unlikely to be accomplished without some form of systematic genocidal process, presumably presided over by that ‘heroic’ Nazi elite. She is unequivocal, however, in asserting that ‘the noblest section of the Aryan race — Nordic humanity’ would rule this new world.[64]

Through her writings, and her unfailing devotion to Hitler and the Nazis, Devi became an influential figure in postwar racist circles, but her introduction to North America was facilitated by a growing emphasis on transnationalism among racial nationalists. Surveying the devastation in Europe caused by the fighting, many of these racialists saw ethnic divisions as a chief cause of the war. Thus, Oswald Mosley, who had founded the British Union of Fascists in the 1930s, urged Europeans to ‘transcend an exclusive nationalism which divides natural friends and relatives’ and come together ‘as a family, of the same stock and kind.’[65] Francis Parker Yockey, a US citizen of German descent, made similar arguments. His 1948 book Imperium—considered a classic today by many white nationalists—drew on Oswald Spengler’s notion of European culture as a living organism to urge a pan-European union which could ensure that organism’s survival. National chauvinism did not disappear, and many racial nationalists still saw their ethnicity as the basis of their race; however, a transnational white nationalism grounded in a pan-ethnic conception of race took root and began to flourish.

Across the Atlantic in the United States, George Lincoln Rockwell, a World War II veteran who had been active in racist organizations since the early 1950s, founded the American Nazi Party (ANP) in 1959. Rockwell sought to resuscitate Nazism, this time as an international political movement. Like Mosley and Yockey, he wrote a book, 1967’s White Power, which called for a pan-ethnic white nationalism. However, Rockwell extended his efforts well beyond the literary realm. In 1962, Rockwell traveled to the UK to meet with his European counterparts. Together, they issued the Cotswold Declaration which founded the World Union of National Socialists (WUNS), an international organization headed up by Rockwell. WUNS barely lasted through the 1960s, and it never emerged into the major international movement Rockwell had intended; nevertheless, it established chapters around the world and became a critical means for distributing white nationalist material internationally.[66]

For Devi, who had been present at the founding of WUNS and was a signatory on the Cotswold Declaration, the WUNS network provided an international profile which ‘greatly extended [her] range of contacts and ideological influence.’[67] WUNS embraced her ideas, publishing condensed versions of her books The Lightning and the Sun, Gold in the Furnace, and Defiance in the organization’s long-form journal National Socialist World. Introducing The Lightning and the Sun in the journal’s inaugural issue, editor William Luther Pierce notes that, despite making ‘a powerful and lasting impression,’ Devi’s ‘works have heretofore had only a very limited circulation,’ something which WUNS was endeavoring to correct.[68] Here, WUNS was successful; the organization introduced Devi to a broad, international readership and ensured that her ideas would find a home in white nationalism to this day.

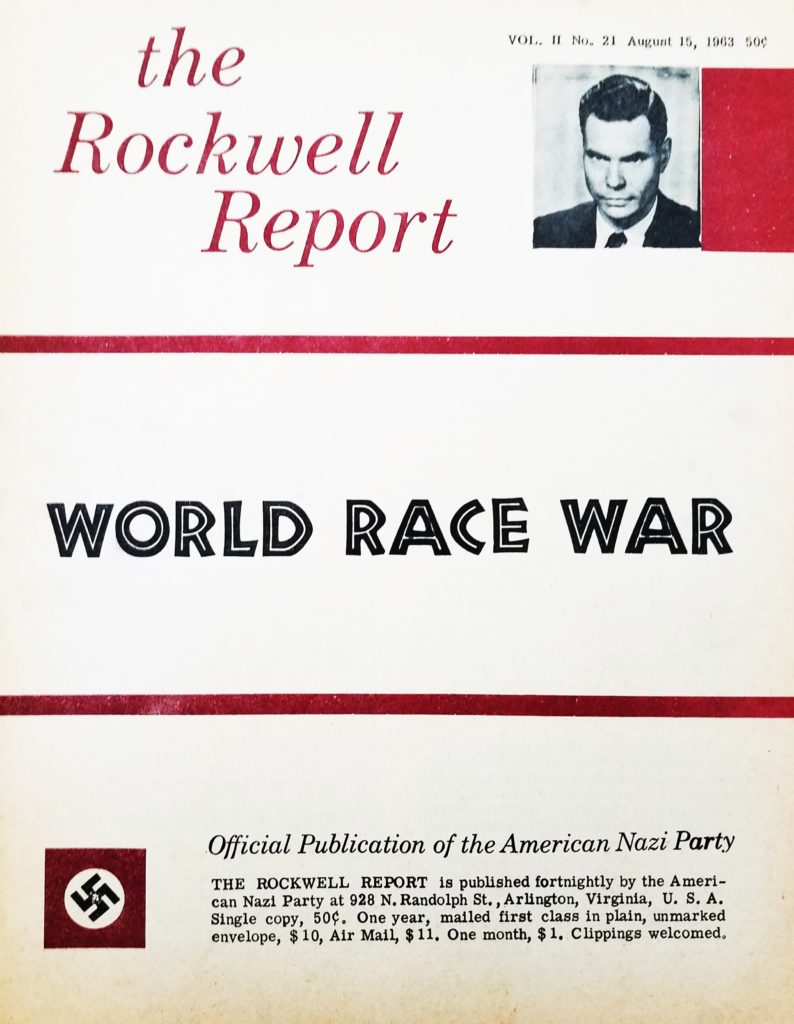

Rockwell’s eponymous publication was not concerned with environmental issues. Image courtesy the author.

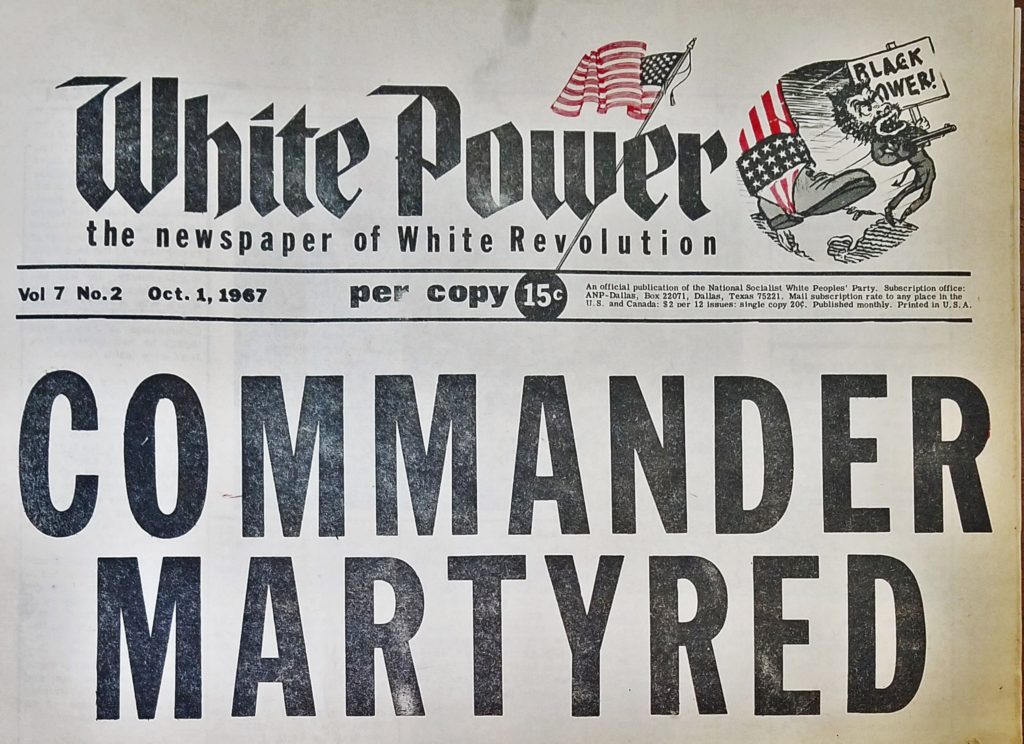

Devi’s environmental concerns, however, did not immediately preoccupy the ANP. Rockwell’s own publication, The Rockwell Report, makes scant reference to such issues. Rockwell himself did not seem to be committed to the finer points of völkisch nationalism, even if he did admire Hitler; tellingly, his writing and official party material appear to be broadly absent of anti-capitalist messages, as well as valorizations of nature and environmental protection. Following Rockwell’s assassination in August of 1967, however, the party’s outlook changed significantly. Now operating as the National Socialist White People’s Party (NSWPP)—a change Rockwell had instituted shortly before his assassination—the party came under the leadership of former party deputy Matt Koehl. An ardent admirer of Nazism who venerated Hitler with religious zeal, Koehl maintained close ties with Devi and brought her völkisch-inflected worldview to the NSWPP.[69]

After Rockwell’s death, White Power began addressing environmental concerns frequently. Image courtesy the author.

This included a turn toward embracing environmental protectionism. In January of 1972, the NSWPP ran a full-page photograph in its newspaper White Power depicting a smoggy view of the New York skyline. Text at the top of the image reads ‘The End of Man?’ Text at the bottom declares: ‘This is what THEY have in mind….They are working overtime to New Yorkerize the rest of the world and turn us into consumer-serfs to a scabby bunch of international bankers roosting here. Pollution, yes. Every kind in the book. The anti-life, anti-nature Establishment has everything from smoke and food additives to pornography. Name your poison.’[70] The text goes on to connect environmental pollution to the despoilment of racial purity.

Völkisch environmentalism had become a concern for the NSWPP, and the party would continue to feature it in their publications. Later that year, expressing their commitment to this new concern, the party began to regularly run a column which detailed its ‘Ten Party Goals.’ Along with ‘White World Solidarity’ and ‘An Honest Economy,’ the NSWPP declared ‘Environmental Health’ as one of its chief objectives, stating that ‘we must…protect the gifts which Nature has bestowed on America. We must eliminate all forms of pollution—not only chemical, but racial and moral.’[71] The following year, another issue of White Power featured a single-frame comic which depicts a grotesque caricature of a black person robbing a white person at gunpoint. In the background, the smokestacks of a factory spew thick black smoke into the air. Closer to the foreground, plastered to a brick wall, is a poster depicting another grotesque caricature, this time of a Jewish person, which reads ‘Big Brother Sez: Pollution Is Good For You! All Criminals Are White People! Jews Are Your Benefactors!.’[72] The suggestion here is that the white race is imperiled both individually, by contact with racial others, and collectively, through the destruction of the environment. Presiding over both threats are the Jewish people.

Like Koehl, National Socialist World editor William Luther Pierce would also maintain close ties with Devi. In the years following Rockwell’s death, Pierce left the NSWPP and went on to found his own organization, the National Alliance, in the early 1970s. From its early days, the National Alliance made environmental concerns a core part of its outlook. Its periodical Attack! regularly denounced ‘our over-organized, over-crowded, over-adulterated, over-mechanized, over-synthesized, over-polluted civilization.’[73] Echoing its völkisch forebears, Pierce and the National Alliance laid the responsibility for environmental degradation on an ‘unrelieved materialism’ insinuated into ‘Western man’s world view’ by Jewish conspirators.[74] A 1982 article in the organization’s newspaper National Vanguard, successor to Attack!, titled ‘What Are They Doing to Our World?’ describes a series of threats to the environment, ranging from soil depletion as a result of industrial agriculture to fossil fuels and air pollution, the result of the Reagan administration’s unchecked drive to promote economic growth over environmental stewardship. The result of this environmental destruction, the article continues, will be a despoliation of the white race as well, an outcome that ‘cannot be halted until we have men in charge who are not afraid to…face the real problems’—the real problems being a lack of racial values and the maintenance of racial hierarchy.[75]

Pierce also established his own religion, Cosmotheism, as the official theological doctrine of the National Alliance. Cosmotheism proposes that the universe inevitably ‘follows the Path of Life,’ a cosmic evolutionary development whereby living things struggle amongst each other to attain perfection. As a result of this struggle, ‘men [are] ranked in value,’ particularly by race, with some races—presumably the white race—better suited to realizing the ‘One Purpose’ of ‘Divine Consciousness,’ the maintenance of racial purity and the fulfillment of cosmic perfection.[76] Seeking a higher state in this hierarchy is part of ‘man’s Divine nature’ which ‘inspires his efforts to act in accord with the urgings of his race-soul.’[77] Like the völkisch tradition before him, Pierce unites race and nature in a union which inscribes racial purity and hierarchy into the natural order of world and cosmos. Such a hierarchy was an unavoidable ‘law’ of nature which was disregarded only at great peril and affront to the divine ordering of the universe. Juxtaposed to the National Alliance’s emphasis on environmental preservation, we can understand an important part of this maintenance of racial purity as embedded in humanity’s relationship to nature and its preservation of the environment, again in keeping with Pierce’s völkisch forebears.

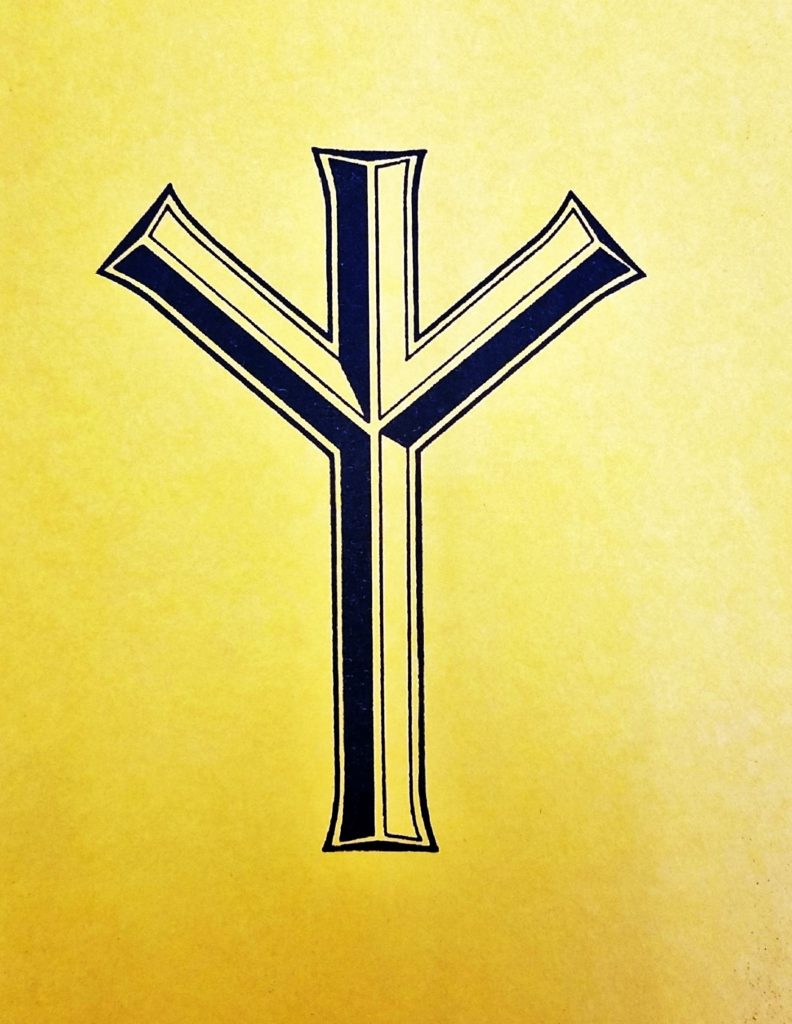

The cover of Pierce’s 1979 Cosmotheism pamphlet On Living Things, depicting the Life Rune. Image courtesy the author.

These intellectual debts are also more than implicit: alongside Devi, Pierce and the National Alliance recognized other völkisch writers as influences. Pierce wrote glowingly of Fichte’s nationalism and his Addresses to the German Nation, calling the German philosopher a ‘hero’ whose writings ‘mold[ed] young men and women into principled members of their nation and race.’[78] He also adopted for the symbol of both the National Alliance and Cosmotheism the ‘life rune,’ a character in the runic alphabet. An article published in National Vanguard discussing the rune’s history and significance notes that its incarnation as a rune representing life dates back to the ‘the late 19th/early 20th century Romantic runology of Guido von List.’[79]

Together, the NSWPP and the National Alliance informed a considerable segment of US white nationalism in the 1970s. The NSWPP remained a fairly small organization under Koehl’s leadership. His abrasive personality made long tenures in the organization a rarity, with many members joining and departing rather quickly. As a result of this ‘constant turnover,’ however, many white nationalist individuals and organizations prominent through the end of the century ‘have roots in the NSWPP.’[80] Pierce and the National Alliance, on the other hand, would remain a significant institution of US white nationalism for three decades, until Pierce’s death in 2002. Active in distributing racist music through its labels Resistance Records and Cymophane Productions, as well as an early adopter of using the internet to promote its message, the National Alliance played an important role in circulating völkisch racism in the US.

The organization also contributed greatly to the milieu Lane circulated in. It is not clear whether Lane himself was ever a member of the National Alliance; nevertheless, Bob Mathews, the founder of The Order whom Lane refers to with religious reverence throughout his writings, was an active member of the Alliance. Mathews derived inspiration for The Order from Pierce’s infamous novel The Turner Diaries, which tells the story of a white nationalist terrorist organization, also called The Order, that ignites a race war through a series of terrorist attacks. Cosmotheist theology abounds throughout the novel and it is likely that The Order’s doctrine was shaped by Pierce’s book.[81]

Lane’s own religious ideas certainly seem to closely resemble those of Cosmotheism, and völkisch thought more broadly. The notion of nature’s highest law being racial preservation, discussed above, which pervades his writing on nature and Wotanism, recalls List’s assertions about nature’s ‘primal law’ and Cosmotheism’s ‘One Purpose’ behind ‘Divine Nature,’ both of which center on racial purity and preservation. And just as the urging to follow this divine law of Cosmotheism emanates from the ‘race-soul’, so too does Lane contend, in the introduction to Creed of Iron, that ‘the attempt to express reverence for nature and the creative force…behind it must spring from the race soul of the Folk.’[82] Further demonstrating his intellectual debt to völkisch nationalism, the page opposite the introduction features a photograph of List above a dedication commemorating him as ‘the great Wotanist and Runemaster of the 20th Century.’[83]

Race, Nature, and Nationalism’s Communities

‘We were born from our lands and our own culture was molded by these same lands….Each nation and each ethnicity was melded by their own environment and if they are to be protected so must their own environment.’[84] By emphasizing in his manifesto the link between land and race, nation and nature, the Christchurch shooter tapped into the larger current of thought running from German racial nationalists to David Lane and beyond. Indeed, the manifesto itself is a patchwork of references to white nationalism’s intellectual tradition; Mosley, for instance, is cited while the phrase ‘a future for white children’—the closing line of the 14 Words—is repeated in several places throughout the text. To borrow a metaphor from Lane, it is one more link in a long chain stretching from nineteenth-century Germany to today.

Thus, tracing the genealogy of this conception of nature and its role in articulating racial identity not only highlights this lineage, but also provides a window into the development from narrow, ethnically-focused nationalism to a comprehensive, pan-ethnic white identity. It is helpful here to recall Raymond Williams’s injunction against treating the elements of a deeply interrelated and always developing social life ‘in a habitual past tense’ as ‘finished products’ and ‘fixed forms.’[85] In that sense, it is not that there was an inherently stable ethnic nationalism which gave way to an equally fixed pan-ethnic nationalism. Rather, there is a complex, interrelated set of social processes we recognize as nationalism which continues to develop and even incorporate contradictory aspects like ethnic and pan-ethnic conceptions.

Considering these processes as nationalism(s), moreover, invites us to think about the communities which they construct and are constructed by. Drawing on Benedict Anderson’s work on nationalism as an ‘imagined community’ derived out of shared linguistic and literary bonds, we can think of racial nationalism in a similar sense.[86] This is a community drawn together around common concerns expressed in a shared literature that spans two centuries. ‘Imagined’ is likely not the most accurate term, however. Shared literary and linguistic communities were not simply imagined; they were experienced by their constituents, who played active roles in contributing to those communities, in no small part by helping to define the symbols which came to represent them. Experience also points us toward a broader terrain of material deployed in the construction of a national community. Nineteenth-century German nationalists drew on the turmoil of occupation and industrialization to define their national community as imperiled. These experiences shaped how they understood their national symbols, as well, characterizing nature and the forest as a precarious heritage which required defense lest they were to perish.

That this community came to extend beyond its ethno-linguistic confines demands particular attention, especially in terms of its broadening of appeal. Racial nationalists outside of Germany recognized something in the anxieties of their Teutonic counterparts, something which helped to define a key component of the developing white nationalist community. If national communities are developed from shared experience, there is something common between both that warrants further investigation. We should ask why this relationship between race, nature, and imperilment is so durable. How does it continue to find an audience generation after generation? Answering such questions exceeds the space available in a single article, but it is important to ask if our modern, capitalist way of life, entrenched now for centuries with a voracious appetite for consuming natural and human resources, has contributed foundationally to the development and maintenance of white nationalism’s experienced community.

This concern for the environment and the wellbeing of our world should also reframe how we think of white nationalism. While we rightly understand it in terms of hate—hate for others, hate for difference, and so on—we also need to understand this sort of racialism in terms of love. There is no reason to assume that white nationalists are disingenuous about their love of the environment or the natural world represented by the forest. As such, we should be asking how such love motivates them, stirs them to activism and to resistance, and helps them to mobilize others to their point of view. If we are to meaningfully address the ongoing challenge of white nationalism in our societies, a better understanding of this love is essential.

[1] Lane, David. 1999. Deceived, Damned, and Defiant: The Revolutionary Writings of David Lane. St. Maries: 14 Word Press. 93

[2] Mudde, Cas. 2007. Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 12

[3] Johnson, Greg. 2016. ‘American Ethnic Identity.’ Counter-Currents. Available online at: https://www.counter-currents.com/2016/10/american-ethnic-identity/ (Accessed 12 December 2017).

[4] Mackey, Robert. 2016. ‘‘America Belongs to White Men,’ Alt-Right Founder Says.’ The Intercept. Available online at: https://theintercept.com/2016/12/07/america-belongs-white-men-alt-right-founder-says/.

[5] Mosse, George L. 1981. The Crisis of German Ideology: Intellectual Origins of the Third Reich. New York: Howard Fertig. 17

[6] Futrell, Robert and Pete Simi. 2004. ‘Free Spaces, Collective Identity, and the Persistence of U.S. White Power Activism.’ Social Problems 51(1): 16-42. 18

[11] Lane 1997. ‘Introduction.’ Ron McVan. Creed of Iron. St. Maries: 14 Word Press.

[17] Brose, Eric Dorn. 2013. German History 1789-1871: From the Holy Roman Empire to the Bismarckian Reich. New York: Berghahn. 12

[18] Whaley, Joachim. 2006. ‘‘Reich, Nation, Volk’: Early Modern Perspectives.’ The Modern Language Review 101(2): 442-455. 453

[19] Rowe, Michael. 2009. ‘The Political Culture of the Holy Roman Empire on the Eve of its Destruction.’ Alan Forrest and Peter H. Wilson, Eds. The Bee and the Eagle: Napoleonic France and the End of the Holy Roman Empire, 1806. New York: Palgrave MacMillan.

[21] Hagemann, Karen. 2009. ‘‘Desperation to the Utmost’: The Defeat of 1806 and the French Occupation in Prussian Experience and Perception.’ Alan Forrest and Peter H. Wilson, Eds. The Bee and the Eagle: Napoleonic France and the End of the Holy Roman Empire, 1806. New York: Palgrave MacMillan. 207

[23] Fichte, Johann Gottlieb. 2009. Addresses to the German Nation. Trans. Gregory Moore. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 155

[28] Arndt, Ernst Moritz. 2008. ‘The German Fatherland.’ Rafe Blaufarb, Ed. Napoleon: Symbol for an Age, a Brief History with Documents. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s. 187-188

[31] Riehl, Wilhelm Heinrich. 1990. The Natural History of the German People. Trans. David J. Diephouse. Lewiston: Edwin Mellen Press. 47

[32] Wilson, Jeffrey K. 2012. The German Forest: Nature, Identity, and the Contestation of a National Symbol 1871-1914. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. 20

[35] Imort, Michael. 2005. ‘A Sylvan People: Wilhelmine Forestry and the Forest as a Symbol of Germandom.’ Thomas Lekan and Thomas Zeller. Eds. Germany’s Nature: Cultural Landscapes and Environmental History. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. 57-58

[36] Mosse, George L. 1975. The Nationalization of the Masses: Political Symbolism and Mass Movements in Germany from the Napoleonic Wars Through the Third Reich. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. 60

[39] Lekan, Thomas M. 2004. Imagining the Nation in Nature: Landscape Preservation and German Identity, 1885-1945. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. 58

[41] Goodrick-Clarke, Nicholas. 2004. The Occult Roots of Nazism: Secret Aryan Cults and Their Influence on Nazi Ideology. London: Tauris Parke Paperbacks. 35

[42] List, Guido von. 1988. The Secret of the Runes. Trans. Stephen E. Flowers. Rochester: Destiny Books. 52-53

[44] List, Guido von. 2015. The Rita of the Ario-Germanen. No place of publication: 55 Club. 19

[46] Chamberlain, Houston Stewart. 2015. Aryan Worldview. Trans. Hadding Scott. London: The Palingenesis Project. 40

[49] Chamberlain, Houston Stewart. 2005. Political Ideals. Trans. Alexander Jacob. Lanham: University Press of America. 64

[52] Field, Geoffrey C. 1981. Evangelist of Race: The Germanic Vision of Houston Stewart Chamberlain. New York: Columbia University Press. 160

[55] Koehne, Samuel. 2014. ‘Were the National Socialists a Völkisch Party? Paganism, Christianity, and the Nazi Christmas.’ Central European History 47: 760-790.

[57] Griffin, Roger. 2003. ‘From Slime Mould to Rhizome: An Introduction to the Groupuscular Right.’ Patterns of Prejudice 37(1): 27-50. 38

[58] Devi, Savitri. 1958. The Lightning and the Sun. Calcutta: Temple Press. 220

[61] Devi, Savitri. 1959. The Impeachment of Man. Calcutta. 10

[65] Mosley, Oswald. 1947. The Alternative. Ramsbury: Mosley Publications. 14

[66] Simonelli, Frederick J. 1998. ‘The World Union of National Socialists and Postwar Transatlantic Nazi Revival.’ Jeffrey Kaplan and Torre Bjørgo. Eds. Nation and Race: The Developing Euro-American Racist Subculture. Boston: Northeastern University Press. 43

[67] Goodrick-Clarke, Nicholas. 1998. Hitler’s Priestess: Savitri Devi, the Hindu-Aryan Myth, and Neo-Nazism. New York: New York University Press. 203

[68] Pierce, William Luther. 1966. ‘Editorial.’ National Socialist World 1: 3-4. 4

[69] Goodrick-Clarke 1998, 209

[70] NSWPP. 1972a. White Power. No. 23, January. 3

[71] NSWPP. 1972b. White Power. No. 27, May. 5

[72] NSWPP. 1973. White Power. No. 39, May. 4

[73] Strom, Kevin Alfred. 1984. The Best of Attack! and National Vanguard Tabloid. Arlington: National Vanguard Books. 4

[76] Pierce, William Luther. 1979. On Living Things. Arlington: The Cosmotheist Community. 5-7

[79] Dewitt, Jim. 1985. The History and Significance of the Life Rune. National Vanguard. Available online at: http://williamlutherpierce.blogspot.com/2012/01/history-significance-of-life-rune-by.html.

[80] Kaplan, Jeffrey. 2000. Encyclopedia of White Power. Walnut Creek: Alta Mira Press. 227

[81] Berry, Damon T. 2017. Blood & Faith: Christianity in American White Nationalism. Syracuse, US: Syracuse University Press. 63-64

[84] Tarrant, Brenton. 2019. The Great Replacement: Towards a New Society.

[85] Williams, Raymond. 1977. Marxism and Literature. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 128-139

[86] Anderson, Benedict. 2006. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso.

Kevan A. Feshami is a doctoral candidate in the Media Studies department at the University of Colorado Boulder. His research focuses on the history and contemporary media activism of white nationalist movements. He is currently writing a dissertation which examines the historical development of the white genocide myth, a conspiracy theory trading in white racial imperilment, as a centralizing theme in the development of a transnational white nationalist movement. The project also looks at how narratives of white genocide are deployed through digital media to expand the scope of white nationalist messaging.