Mikayla Journée

Preface, Part I: Sweet Potatoes

Kumara is the Māori kupu (word) for sweet potato, one of the primary crops of pre-European Aotearoa New Zealand. The kumara has sustained its prominence in local diets and on supermarket shelves alongside the white potato varieties. Today, there are also a number of restorative gardening initiatives across the country, restoring knowledge around kumara gardening.[1] Sir Haare Williams (Ngāi Tūhoe, Te Aitanga-a-Mahaki) has used kumara as a storytelling symbol for survival – both physical and cultural.[2] Williams describes his childhood as one of ‘Gardens. Lots of gardens. Extensive gardens for just three people, one a moko (grandchild) who inherited their grief through the power of storytelling.’[3] The māra kai (food garden) was not only about food. It was also about cultural survival and restoring the mana of the garden and of kai (food). Whilst he ‘didn’t understand what was meant by listening with the trees and to the life of the land, sky and ocean,’ Williams writes:

There was always greater responsibility to ensure the preservation of mauri (life force) in all things that provided for whanau (family) wellness. Planting and harvesting were marked with constraints and rituals through karakia (prayer) and chants. Each seasonal sign, like the appearance of new leaves or the moulting of feathers signalled times for mediation with nature.[4]

The garden can be a performance of identity and ideology. A place where food is produced, where knowledge is held, where traditions are performed, where stories are told. A place for surviving and a place for thriving.

Preface, Part II: Companion Plant

The periwinkle is a small, violet-toned, five petalled, flower, almost hidden amongst a mass of a pernicious, weedy, stringy leafage. Moving through the trip hazard mass of ground cover, I pick the purple flowers, peel away the petals, gently, slowly, to find inside a tiny fairy toothbrush, or is it a tooth fairy’s wand?, I can’t ever quite remember. This cloak of weed smothers the whenua (land). It doesn’t belong here. In a small pot at my front door I watch as a few stringy shoots of this periwinkle develop a glossy green heft. It starts to reach well beyond its remit now. Tendrils elongate and extend to the structures and surfaces and plants in its vicinity. I pull its tendrils into a coil around its own pot, cautious to not let this weed do damage, but still curious to observe its behaviour. Admirable for its tenacity, but its work needs to be edited and scrutinised. This has been my uncomfortable and entirely unglamorous research companion plant; a conceptual space from which I interrogate my positionality in this place. As my research led me to a number of social art practices working with gardens, my own experience of gardens and plants became a site for thinking. As a descendent of British Settlers, I, like the periwinkle, am not from this land, but my tendrils and roots and heritage is embedded here pretty deeply now. The periwinkle seems to have a pernicious symbolism for colonisation; a smothering, weed across the land. But, the periwinkle is also the surprise and delight and dreaminess and storytelling of childhood. The periwinkle is also my great grandmother – the woman who showed me the tooth fairy wands/fairy toothbrushes. And she was an admirable, tough, strong, welcoming, unjudging, matriarch. Periwinkle is now a squishy flora bed upon which my child and I can flop about in, from where I share the first stories of our ancestors and our relationship on this land. The periwinkle is also a cloak or a blanket, perhaps, a heavy embrace. A cloak that is at once a smotherer and a protector. A weed is at once admirable and a nuisance. And who determines what’s a weed anyway?

Introduction: Garden-art and art-gardening

This essay’s two prefaces are performing as positional guideposts. First, a story about kumara and cultural survival in a land whiplashed by colonisation. The second, an autoethnographic reflection (or perhaps what Natalie Loveless might call a situated confessional).[5] In noting that ‘home is a location from which to speak’ — simultaneously domestic, private and political,[6] this work is being done from a home in an Auckland suburb, one with quite a lovely garden, and brings a Pākehā positionality to research on social art history in Aotearoa New Zealand and it’s intersections with geographies and histories. This essay is also a pikopiko, a young fern shoot or a meandering/rambling, from interrelated PhD research.

This essay positions gardening as a form of research-creation.[7]

Whilst gardening-as-art practice is the subject for this essay, running beneath this, in parallel and like an underground conduit, has been the planting and observing of periwinkle – a physical and metaphoric space for personal and positional inquiries into the nature of suburbia, human and non-human relationships, land ownership and colonial weeds. The first agenda for this essay is to establish a local eco-system of this modality of practice, before tending to these central concerns through two case study discussions.

Gardens have always been intimates with art and public art and public gardens have always gone hand in hand. Memorials and statuary are still frequently positioned within the public park or garden. Mark Amery notes this relationship in An Urban Quest for Chlorophyll, a project examples of urban gardening as contemporary art in New Zealand and the ‘cultural mediation of nature in an urban context.’[8]

Amery writes:

Imported trees and flower beds were planted in our cities as memorials alongside public statuary. They are markers of history and time (consider the traditional flower clock), and assertions of beliefs and values. Yet values and beliefs are always changing. Now in our built-up urban environments we’re looking for art to activate spaces and help us rethink the role of plantings: to be valued for function as well as aesthetics.[9]

Gardens and art have shared cultural histories as spaces as places and objects of pleasure, leisure, ownership, order, control. Mastery of agriculture – of soil, of plants, of seasons – is one of, if not the, biggest hallmarks of humanity. Gardens have thus been a site for mastery, at the same time as a way to display of power and control over. The medieval garden was enclosed with high walls and often an allegory for the female body.[10] ‘Flowers, herbs, fruit-bearing trees, fountains, and musical instruments,’ Solnit writes, ‘made them places that speak to all the senses.’[11] As aristocratic residences became palaces more than fortresses, Renaissance gardens became cultivated landscapes to walk and sit and socialise.[12] The garden increasingly became a domain of wealth, power, mastery and control. The European model for the formal garden was one where the chaos of nature, or the wild, was brought under control by men.[13] And whilst the strict formal conventions of the garden were relaxed over time, the garden has remained a place of controlling chaos, of only appearing natural, where wild and tame are in constant negotiation.

Given the public garden’s long shared history with public art, it makes sense that alternative gardening and alternative public art are in dialogue and intertwining too. This article is interested in the garden and gardening as both a site for art and an art practice or process. There is a large body of work engaging the garden and gardening in social art practices in Aotearoa. Engaging with gardens as an artistic and conceptual exercise enables a rich and fertile platform from which to consider social eco-systems. Concepts familiar to gardening: permaculture, companion planting and communities, intertwine in real and metaphoric ways with social art works questioning how we live together. Alternative economies is a dominant point of discussion around this work. Food sovereignty, gift exchange and social enterprise are similarly proposed and demonstrated in art-gardening practices. These are all vital conversations to be having in an era of social and economic precarity. As a method and a site for social art works, gardens have enabled artists to take both grand and humble actions in service of a socially generative kaupapa (purpose).

Aotearoa has fertile soil, both literally and conceptually, and the settler colonial context imbibes ‘the garden’ with complexities and political considerations. Firstly, ecological disasters, food sovereignty, traditional knowledge security and self-determination, are conversations with Colonisation as much as Capitalism. Secondly, many artists are embracing and advocating a viewpoint of the non-human realm as vibrant and agental, and demonstrate a practice of listening to the land. From this positioning, where non-human are our kin, the garden can be in dialogue with us, a teacher, or even a companion. Amanda Yates (Ngāti Rangiwewehi, Ngāti Whakaue, Te Aitanga a Māhaki, Rongowhakaata) and Janine Randerson employ ‘a definition of public that embraces both human concerns and the non-human beings and systems,’ to respond to the urgent demand for ‘turning our attention beyond the subjective, beyond the human, to the entities, object and things that surround us.’[14] Their framework is informed by ‘indigenous paradigms that emphasise the relation connection of entities,’ and Latour’s (and Latour’s followers) ‘object-oriented materialist theory.’[15] Drawing on the Māori worldview, as written about by Mere Roberts, Yates and Randerson frame ‘public’ within the notion of tangata whenua (people of the land) which positions humans as descendent of Papatūānuku (the earth mother).[16] From this origin, they write, our ancestry and familial relationships expand to a much larger, non-human kinship group; landforms and animals and ourselves descend from shared parentage.[17]

The case studies in this article come from PhD research on social art practices in Aotearoa New Zealand. It looks at the practices of Monique Redmond and Sarah Smuts Kennedy and their work with the garden and gardening. Referring to specific art works as well as their broader conceptual frameworks, their work demonstrates how the garden can expand ontologies to give attention to the interrelations with the non-human realm, enable a making of friends in a socially isolating world, and provide a platform for action to manifest alternative economies and food systems to imagine better futures for people and planet. The garden is a vital zone for humanity, across which our largest human dilemmas are determined, where everything’s at stake. And they can be battlegrounds and testing grounds and safe grounds for futurity.

A topographical landscape of social, garden-art practices in Aotearoa

A study of the forms and features of social, art-gardening in Aotearoa and the specificities of this practice as a social and public art form, reveals a number of consistent themes. On one hand, artists tend to work with gardens to address inequality and sovereignty issues, where land ownership and food control are the primary subject matters. On another hand, artists work with the garden in order to explore vital materialism – decentring the human and opening themselves and others up to symbiosis with the non-human realm. By listening and responding to plants and animals, there is an empathic de-centring that is fundamentally aiming to reconfigure our ecological impact. By using social art as a form, artists are able to engage in this exploration with others, which not only extends these thought experiments beyond themselves, but also offers a counterpart to the dominant models for art, for the economy and for the social. Returning to the earth and to face to face exchange, whether as an art practice or as a lifestyle, is an understandable and necessary reaction to the social and economic dynamics of our times.

There is a ‘utopic tradition’ for contemporary artists who centre ecology and economy struggles in their work, in the many eco-artist-activists of the 1970s.[18] In a durational intervention from 1965-78 called Time Landscape, Alan Sonfist ‘returned half a block in New York’s Greenwich Village to its pre-colonial, native condition, protecting it from surrounding invasive species, urbanisation, and development.’[19] Guerrilla Gardening and Land Art practices in the 1970s in Aotearoa were similarly engaging in broad anti-authoritarian and ecological activisms. This is the decade that curator and historian, Tina Barton, refers to as the time the art world came of age in New Zealand.[20] The art market was established, artists were more connected with global trends, we began writing our own art histories, and at the same as that, began expanding practices well beyond Nationalist narratives.[21] This expanding of practices included new media, as well as experiments in non-object practices, and what has come to be described as ‘Post-Object’ sculpture. Performance art in public spaces was one such space of re-orientation. Barry Thomas’ Cabbage Patch (1977) in Wellington was a guerrilla gardening, public art intervention whereby the artist commandeered a vacant lot in the centre of the city’s capital. Whilst the corner site was in stasis between demolition and rebuild, Thomas planted a garden of cabbages and staged a number of disruptive and quirky events, as a symbolic reclaiming of the city for a space for ‘the people.’

There was been a noticeable (re)turn to urban take-backs throughout the 2010s in New Zealand, and increasingly pressure upon colonial and institutional barriers to better facilitate non-Western ways of living. In the garden city of Christchurch, the 2011 post-earthquake response was majorly characterised by gardening in vacant urban lots. Out of rubble, saplings grew, literally and metaphorically, as a vehicle of social repair. As Lara Strongman frames this particular practice in context ‘post-disaster gardening.’[22] The city’s public art and Placemaking practices still bear the legacy of this collective trauma and creative context. There is a notable degree of intersection between contemporary public art and Urban Design disciplines. Beyond the emotionally charged Christchurch rebuild context, urban redesigns were already underway across the country. ‘Placemaking’ projects burst through the 2010s with green spaces, pocket parks and community gardens established in various urban precincts as the proposed antidote to a concrete hangover; these were at times meaningful, and at times shallow reparations for a history of razing land and reclaiming foreshores. Rebecca Kiddle (Ngāti Porou, Ngā Puhi), negotiates with dominant Western frameworks for Placemaking.[23] Attending to the threat of homogenisation from neoliberal forces, when done well, Kiddle says, Placemaking responds to a community’s needs and puts the ‘place’ back into urban design.[24] Māori Placemaking, as a pre-colonial, social-spatial approach, centres on familial units of whānau (extended family) and hapū (sub tribe, or extended whānau), values and practices which were erased with Colonial city-building and much more recent urban migrations away from familial settlements.[25] Kiddle argues that the erasure of Māori continues today, where traditional land is forced into development, iwi (tribal) and hapū groups are forced to work with local government in decision making processes and private ownership and financial structures make communal ownership models difficult to establish.[26] Indigenous architects and urban planners are attending to this need for design for indigenous ways of life and but these values are dispersing across the country, in multiple spaces. In many cases, social art practices are in synergy and allyship with these counter-hegemonic and social-regeneration values.

With decolonial and more-than-human contexts in mind, there have been a number of garden-art works and projects addressing these themes. Some works existed for short periods of time, annuals, we might say; bursts of short lived colour. A.D. Shierning has returned to the garden as a site of their practice. Freedom Fruit Gardens (2007 onwards), Hauora Gardens (2014) in collaboration with Richard Orjis and Plant and Oi Oi (2014) grew out of the same contextual thrust that generated the urban placemaking community garden initiatives around Auckland and many other cities. For Walking in Trees (2019), Richard Orjis built a temporary structure in one of Auckland’s primary public gardens to enable public the experience of being up amongst the sub-canopy.[27] Xin Cheng’s practice has also engaged with urban gardens, and they returns to urban flotsam and jetsam and human and non-human interrelations as a medium. For an exhibition entitled They covered the house in stories (2021), Xin Cheng and Eleanor Cooper examined and exchanged experiences of two bodies of water and through audio, text publication and sculpture, seeking to attune visitors senses to the more-than-human habitants we share the city with.[28] In collaboration with Adam Ben-Dror, Cheng has also documented the Common Unity garden project, representing human and non-human subjects at the community garden, in a film work entitled Making Like a Forest (2020).[29] Jill Sorensen has also recently engaged in a project of cohabitation with the objects and plants in her home, as a participatory art practice between human and non-human.[30]

More recently, within a Covid context, artists and creative communities were forced to adapt, another synergistic theme for plants. Some artists turned toward their own gardens as a site and medium. Chris Berthelsen has employed the suburban berm as a polemical site for art experiments in the public realm. For Berthelsen, the front garden (and its blurry boundaries) has been a conduit and place for making friends and proposing counter-hegemonic solutions to alienating urban design.[31] The gallery Vunilagi Vou also reconstituted itself into a suburban south Auckland garage and garden site, as an economic and social strategy during the pandemic.[32] Pivoting on the house-boundedness of Covid lockdowns, Vunilagi Voudeveloped and produced a programme of exhibitions and events in the garage and backyard garden – the garden, in this case, was the site and facilitator for the social and art in a time of economic uncertainty and social dislocation. Not only did this model provide a stable alternative during a time of precarity, forced social isolation and the following social anxieties, it also became a platform from which polemical dialogue about South Auckland’s particular stereotype of anti-social behaviours in the suburban garage or backyard garden, played out in public discourse.[33] As these two recent examples attest, the suburban garden, at least in Tamaki Makaurau Auckland, has proven to be a contentious battleground for social, cultural and political ideologies.

This topography has barely touched the sides of this art form, suffice to say, there is a rich art history still to tend to for contemporary social-art-gardening practices in Aotearoa. The following two case studies might easily be described as perennial practices, and they encapsulate many of the concerns that are consistently seen in garden-art works. Monique Redmond planted the seeds for her current practices some thirty years ago, and has sustained the turns and trends of this art form. Sarah Smuts Kennedy’s For the Love of Bees(2015-ongoing) has similarly outlived the life cycle of most placemaking and garden-art projects alike.

Flowers, flowers, fruit, vases and flowers

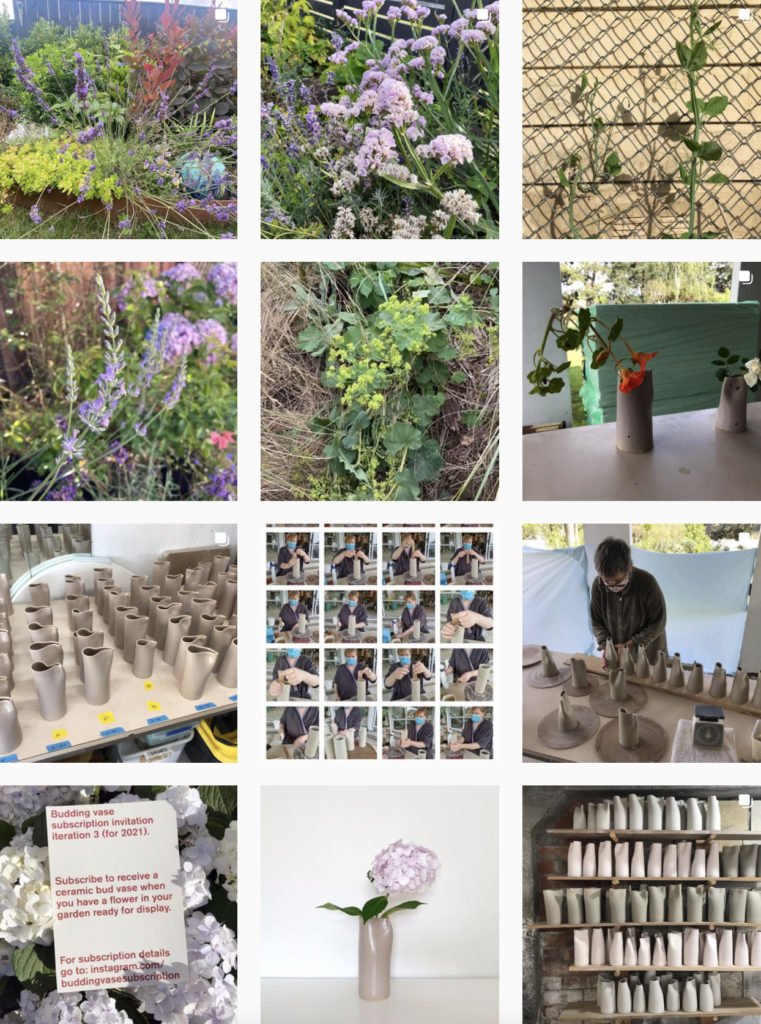

Monique Redmond’s practice is almost entirely collaborative, and whilst each project has tended to have its season, Redmond’s social art practice spans and has sustained across three decades. Redmond has become increasingly known for her floral associations. Collaborative projects have previously included Suburban Floral Association (2011) with Tania Eccleston, A full season (2016) with Layne Waerea, and continues to include Budding vase subscription (2015-ongoing) with Harriet Stockman and the collective Public Share. Public Share’s practice hinges on labour and exchange as a conceptual point for departure as well as a practice.[34] Collectively making ceramics in large quantities to then facilitate large event-based tea breaks, become the art’s form and the topic for discussion. Public Share engage with topics around work in some way; workers conditions, who gets to work and how. For Budding vase subscription, Redmond and Stockman annually produce a series of bud vases which are offered to the public in exchange for an image and story featuring florals.[35] These projects ask for very little in return, other than respect for the kaupapa (purpose). Sharing in a meaningful, if fleeting, human to human exchange is all that’s sought.[36]

Figure 1. Monique Redmond and Harriet Stockman, Budding vase subscription (2015-ongoing). Photographic documentation of Instagram posts showing vase production, notice of subscription, flowers and vases in situ. Photo courtesy of Monique Redmond.

At the time of writing, feijoas are littering the grounds of the suburban gardens of Auckland. Many feijoa tree owners feel overwhelmed by the sheer quantity of this produce and they can be hard to shift to neighbours, friends and family. Many hundreds of feijoas inevitably rot into the ground, and the subsequent fruit flies disturb the suburban garden’s serenity. A full season (2016), Redmond’s collaboration with Layne Waerea, was an open ended project with multiple sites of exchange.[37] For Public Service (2014), the artists invited the owners of front gardens with fruit trees into an exchange. They offered services to these fruit tree owners to bake or preserve their fruit, which were then delivered back to them.[38] For We want your feijoas (2015), the artists’ proposition was to specifically exchange feijoas for baking or preserves.[39] A public service artwork and catalyst for thought and dialogue around our homogenous food economy and the disconnect between grower and eater.

Redmond understands the city’s geography by its flowers. One of the repetitive actions characteristic of her practice is the ‘drive by’ and bloom spotting call outs which has accumulated into an immense urban floral map.[40] Redmond has taken hundreds of photos over many years of flowering trees and shrubs across the suburbs of Auckland, with the iPhone able to easily generate a floral map of the city from her photographs.[41] ‘When they’re not in flower,’ she says, ‘the suburban streets are like spaces in waiting.’[42] Flowers are a symbolic medium for the ephemeral and temporal art practice. They have a similarly temporal quality to them. In a self-delivered work, FLOWERING NOW (2018), Redmond placed community notice ads (in print media format) with curious, conceptual messages that announce where and when a certain shrub or tree in a certain suburban street is in flower. The project description reads: ‘Adverts are placed in the Classifieds section of The New Zealand Herald daily newspaper under Community Notices, announcing what is flowering now in the suburbs. These announcements are put in the paper concurrent to the artist’s noticing, so appear on different days and weeks as sighted. (First published on 23 August 2018; 97 adverts as of 18 August 23 December 2021 – print edition. Ongoing–.)’[43] The first ad listing read: ‘Great excitement, the best rhody in Mt Albert is out! It’s on Martin Ave. Definitely worth driving by. 23.08.18.’[44] Asking for nothing in return, Redmond’s propositions entered the public realm, under the radar, existing as potential moments of surprise and delight, for strangers. Micro-interruptions of enjoyable thoughts and the possibility of participation in an inspired, floral drive-by.

Figure.2. Monique Redmond, FLOWERING NOW (2018-ongoing), Digital Photograph of Classified listing in The New Zealand Herald overlaying the flowering tree. Image courtesy of Monique Redmond.

Figure 3. Monique Redmond, FLOWERING NOW (2018-ongoing), Digital Photograph of Classified listing in The New Zealand Herald overlaying the flowering tree. Image courtesy of Monique Redmond.

Redmond conceives of her practice as a set of social modalities and utilises the material object, in many cases, flowers, as a conduit for a social exchange – conversations, storytelling and the exchanging of anecdotes.[45] Along with the gift and fresh flowers, labour, repetitive action and duration are central to Redmond’s practice. Redmond’s reflective research generated a series of concepts that by-pass the all too often relied on framing devices of Participation, Collaboration, the Event and so on. Instead, Redmond relaxes into notions of Enthusiasm, Enjoyment and Appreciation as worthy artistic working modalities, which are of course as well, a set of accessible, real world values.[46] Dissemination, dispersal and resonance are key concepts across Redmond’s personal and collaborative practice, and Redmond’s entire practice has a quiet and conceptual presence.[47] As an artist, she embraces the fleeting, the barely there, the nearly invisible and is profoundly comfortable with the uncertainty of outcome.[48] Taking enjoyment in other artists’ practices that are similarly under the radar, works that almost need to be ‘noticed into existence’, Redmond embraces and leads with an understanding that resonance and significant presence can be unknown and quiet.[49] Just like gardens: quiet presences that have significant resonances. Though perhaps initially ‘barely there’, accumulation and duration add to these works form. Over years and decades, Redmond’s practice has become a blooming, social, art garden. Ephemeral, convivial gestures such as Redmond’s resist not only the commercial art world but consistently deter and defer the artist’s individual identity, added to further by the collaborative naming for each project. At times, just as a gardener, the artist is almost in hiding.

Figure 4. Suburban Floral Association, Shopfront, 2011, Photographic documentation of installation and programme of public events. Image courtesy of Monique Redmond and Tania Eccleston.

In 2011, Redmond and Eccleston developed Suburban Floral Association with an inaugural project called Shopfront. Supported by Letting Space and Auckland Arts Festival, Shopfront was an alternative gardening project for public to come together and bond over flowers. Subsequent projects included THE FLORAL SHOW | LOCAL EXOTIC (2014) with Janet Lilo and Park for a Day (2014) with HOOPLA. From ‘cinema, gallery, seminar space, front yard and living room’, with floral drive by film screenings, flower arranging workshops and cutting exchanges, Shopfront’s form changed and grew over the twelve day duration.[50] Engaging with the idea of still lives, the artists suggest the suburban arena is one of containment and tableaux.[51] The garden, as with the still life, also generates ‘an attentiveness to life and death.’[52] Mark Amery also acknowledges that flowers are far more than ornamentation, noting that when ‘used in memoria, for birthdays and making acknowledgements (“say it with flowers”), they have an important role in engendering exchange and helping create living space.’[53]

Garden writer Hannah Zwartz likened the Suburban Floral Association’s conceptual framework and form to the conceptual ‘front garden,’ places where home owners express (intentionally or unintentionally) their personalities.[54] For Redmond and Eccleston, the suburban front garden was conceived of as a ‘welcoming committee’, a seasonally changing greeting to a home’s owners or visitors.[55] Just as the suburban front garden has a tension between public/private space, it is a space that similarly holds in tension the supposed binary of culture vs nature; tame vs wild.[56] Front gardens are culturally informed – the Pākeha front garden, for example, is most explicitly for show, Zwartz recognises.[57] Front gardens are not places ‘for sitting around in (that’s done in the private backyard), but for chatting over the fence as you bring in the groceries or take out the rubbish.’[58] Zwartz’ commentary on the everchanging nature of the garden is a helpful analogy to the social:

Plant a garden, and it starts instead to morph into something differently shaped. There’s always something new happening in a garden. Weeds enter, but plants also grow and change with the years and with the seasons. Gardens stage small events all the time as different plants grow, bloom and die.[59]

With its malleable form, Shopfront enables us to think through these heterotopic social spaces, all the while offering a public experience for people to bond over beautiful, fleeting things.

Aotearoa New Zealand has been obsessed by the American suburban model. Culturally, New Zealanders strive for the stand alone house and their own outdoor ‘domain’, where a land ownership microcosm is demonstrated in a well-presented, unused, private/public front. The front garden is a demonstration of success and the back garden is where life is more likely to happen. This is the ideological terrain for individualism. The conceptual struggle within the works by Redmond is in how to be better social human creatures – for each other and the planet. Though demonstrably different in approach, Smuts-Kennedy projects are also directly addressing these social and economic ecologies and subverting them with a similar practice of labour and love. As alluded to at the top of this article, gardens have always been associated with privilege. Gardens denote dominance and control over nature and, above all, indicate power in the form of land ownership. Intimates with this discussion then, is land loss and the culminating food sovereignty phenomenon and dilemma for our times.

Eden

‘In most Utopian theories,’ writes Nils Norman, ‘the garden and gardening is almost always present as central to the idea of radical social change.’[60] Some artists, T.J. Demos writes, ‘are now demonstrating, by going far beyond institutional critique…and opting for an explicitly activist and interventionist practice….there is no Eden, no virgin spring to which we may return.’[61] Eden and virgin springs might have gendered associations here, perhaps prompted by this context of the garden as a site of practice, and the garden’s well-established gendered dimension. If the garden is female, with its associations with fertility, life and nourishment, and the act of taming and controlling wild, unwieldy nature into an Eden, is a male domain and display of power and control, where does this leave us in this context? Is the notion, posited here by Demos, that those who have cast aside hope for undoing the harms to Mother Planet, a masculine one too? Is it rather more female to care, to toil, hands in the soil, to keep going, and work toward the utopic, restorative, visions for ourselves, our children and our planet? Certainly possibly, and this runs in tandem to the paradigm of Indigenous-led projects across varying disciplines aiming to similarly demonstrate ‘a way out’, despite the largely Western, male, determination of hopelessness. The Garden of Eden can be a superb spring board from which to view activist, garden-based art practices today. Reclaiming female tropes and re-writing historic paradigms for ‘the garden’ with a decolonial and feminist lens. The Garden of Eden, ‘as an earth bound rather than heavenly idea,’ has been a driving concept for Nils Norman.[62] For the Love of Bees is an example of such artworks that posit, in Demos’ words, ‘transformations and deformations of the systems they engage.’[63]

Figure 5. Sarah Smuts-Kennedy, For the Love of Bees, 2015, Social Sculpture. Image courtesy of Sarah Smuts-Kennedy.

For the Love of Bees (2015-ongoing) has been a social sculpture-come-social enterprise project, generating self-sustaining urban farms in Auckland. Sarah Smuts Kennedy has been the vision holder for this work from its inception until 2022. For the Love of Bees is proposed as a project of ‘partnering with place and planet,’ to create ‘climate change ready infrastructure.’[64] From the outside, For the Love of Bees is an urban, micro-garden project. As a broader kaupapa (purpose) however, the gardens are sites for education on growing food and spaces for critical discussions around food production systems and generational trauma from colonisation. For the Love of Bees has been an essential agonism to dominant hegemonies in the food economy, as well as a much loved space for community. It has also been a vital site for facilitating mana motuhake (self-determination) programmes for the city’s dwellers and a space within which discussions can be held around the dynamics of late stage capitalism and ongoing impacts of colonisation with inner-city communities with lived experience of homelessness in Auckland city.[65] For the Love of Bees gardens and programmes are propositional and performative micro-utopias. Importantly, the work holds a mirror up to the dilemma of our deformed, dominant food economy.

T.J. Demos considers artist-activist interventions that centralise economical and ecological justice and suggests that artists who ‘produce a model of community-driven ecological sustainability,’ go ‘far beyond the institutional critique,’ give ‘shape to abstractions and normally invisible externalities on which both finance and global ecology depend,’ and opt ‘for an explicitly activist and interventionist practice.’[66] Furthermore, he writes, such artists ‘often shun institutional enclosure, privileging the importance of local projects and communities and blurring the distinctions between art and activism.’[67] For the Love of Bees is functioning in this way, as a pedagogic device to reconnect the public to their food production and raise awareness of economic injustices entangled in our daily subsistence. A flurry of public discourse around the dominance of two big supermarket companies in Aotearoa, the ‘duopoly’ and their unhindered growth during Government administered business closures during the pandemic, is top of mind.[68] At the time of writing, inflation has been thick and fast, and this duopoly has been at the primary pain point and at the epicentre of the public discourse. For the Love of Bees has been saying, throughout its existence, that alternatives are lacking and essential. The garden and gardening is fertile ground from which, as Demos writes, art ‘can unravel some of the utopian and critical myths on which “the natural” rests,’ and ‘with a nod to Jameson… challenge the financialization of nature.’[69] Whilst Frederic Jameson was primarily concerned with the naturalisation of the economy, Demos suggests the ‘financialization of nature,’ as the ‘inverse of this neoliberal doctrine,’ ‘threatens to be even more consequential.’[70] Addressing these ideas directly, For the Love of Bees engages with this ‘ideological struggle’ of our time.[71]

When drawing attention to the problem is not enough, some artists do more than representation, straddling both art and activism contexts, and collapsing this art-life divide.[72] This was a starting point for Smuts-Kennedy. Not wanting to make metaphoric work that simply points to issues, For the Love of Bees became about enabling the content and the material of her work to be active in space with the viewer.[73] For the Love of Bees is exemplary of artwork at work, not only in the literal production of food and upskilling publics in how to grow their own, and the possibility for self-determination, but also in its ideological challenge to political norms. In response to an ecological and nutritional crisis, dialogues continue to evolve around regenerative and reparative gardening practices – of no tilling methods, permaculture systems and restoring vital nutrients back into the earth. In parallel to ecological regeneration and reparations, the post-Pandemic and post-digital need for social recuperation, regeneration, reparation, reconstitution is still very much apparent and being demanded across the political sphere and across the Globe.

Permaculture as metaphor for a more sustainable society

For the Love of Bees, which focuses on restoration and biology-first principles as a gardening methodology, is underpinned by Permaculture concepts.[74] As a whole-system approach to gardening and possible model for social ecologies along with vegetative ecologies, Permaculture might be a fruitful metaphor for (better) social ecologies. Nils Norman’s Edible Park (2011) is a similar, durational, public art project and a growing, living permaculture garden, producing vegetables and fruit, built on an unused piece of grassland on the outskirts of the Hague.[75] Like For the Love of Bees, Demos suggests Edible Garden addresses Guattari’s call for new ‘“stock exchanges” of value,’ to resist the current realities by which everything can, and is, a form of currency.[76] The work is a notable international counterpart to For the Love of Bees. At the inner city Edible Park, a central ‘roundhouse’ is a placemaking structure- both adding a sense of permanence, as well as providing function for rest, storage supplies and information.[77] Edible Park was a counter ‘master plan’, conceived in part as a response to the failed city ‘master plan’ that was going to include an amusement park leisure district, a beach, skyscrapers, formula one race track (plans were dropped following the 2008 financial crisis).[78] In Norman’s words, ‘a “no master plan” from below.’[79] For the Love of Bees was similarly a tangent, or foil, to institutional (in)action around sustainability initiatives. In its initial formation, For the Love of Bees was funded by Auckland Council, but driven and developed externally. It was both inside and outside the ‘master planning’ rooms; helpfully distant, but at least for its initial development, structurally secure.

In Edible Park’s project proposal Norman asks: ‘Can a grassroots, biodynamic system that comes out of a utopian tradition operate citywide, become integrated in the city’s existing planning processes and possibly eventually replace them?’ or ‘is this in itself a naive and misplaced utopian idea?’[80] As a living garden, Edible Park intends to investigate whether changing a garden’s design might alter the ‘social organisation and economic distribution systems.’[81] In synergy with this vision, For the Love of Bees was about asking if ‘love and an energy system accelerate behaviour change,’ as well as trying to figure out what it would take for people to participate and engage in performative action.[82] Bees became the metaphor and actual material form to engage and incite commitment from a broader public.[83] More than eco-gardening, both projects are experiments in ‘agro-social construction’ and models for how to link ecology, economy and social life.[84]

Edible Park ‘bucks the dominant trend towards the privatisation of everything,’ and uses permaculture as a ‘method that enables people to build their own functioning ecosystems.’[85] Permaculture is designed to think about these broader, socially relevant aspects.[86] ‘Norman chose permaculture as a trial system,’ Demos writes, ‘because it unfolds onto inclusive social processes, taking into account local weather, soil conditions, geography, and collective subsistence farming – all ingredients for a sustainable society.’[87] It’s in this way that Permaculture as a metaphor for social systems is so apt – a methodology that makes space for the local, for variation, for specificity, for place, for collectivity, for inter-relationality and for something a little more natural.

At one with plants

Sustaining projects such as these through commercial ebbs and flows is the ongoing challenge and one that takes steadfast vision, perseverance and determined resistance. Committed gardeners and diligent gardening. Smuts-Kennedy frames her inward-facing, quiet, object based practice as ‘breathing in’ and her public realm, social practice as ‘breathing out’.[88] It is both a cyclical framework, where one practice informs another, and also one that suggests a perpetual need for keeping energy in balance. Service-based art practices are demanding. Although seemingly in opposition, these modalities are actually always in dialogue. Smuts-Kennedy begins and ends with the human connection to the non-human realm and her art is consistently a vehicle for healing and bringing vibrations of joy to the planet.[89] Beyond its social practice modality, For the Love of Bees is fundamentally engaging with the non-human realm too, and its perhaps this vision that has held For the Love of Bees stable for so long, a perennial in comparison with other annuals.

Figure. 6. Sarah Smuts-Kennedy and Taarati Taiaroa, The Park, 2014, Social sculpture and mixed media installation. Image courtesy of Sarah Smuts-Kennedy.

Smuts-Kennedy has explored these concepts elsewhere in public art. Smuts-Kennedy worked in collaboration with Taarati Taiaroa (Te Āti Awa, Ngāti Tūwharetoa, Ngāti Apa, Ngāti Kotimana) on The Park (2014), a public, garden-art sculpture that used bees as a way to view the city of Auckland through a lens of private/public space.[90] Making homes for bees in Victoria Park, and providing ‘Pasture Paintings’ for their food source, the public were asked to support the gardens and contribute to an online map to visualise the bees point of view.[91] One day, whilst working with bees for The Park, Smuts-Kennedy experienced ‘hive mind’, an entire body/out of body, buzzy experience. The artist was not quite of this world, but rather one with the bees.[92] Whilst this was a personal experience with the non-human realm, understanding and dispersing the resonance, vibrancy, hidden histories, storytelling and mauri (lifeforce) of the land, has been a vital starting point to all of Smuts-Kennedy’s work and practice across various mediums.[93] In this way, Smuts-Kennedy and Redmond’s practice seem to capture a shared sense of the garden’s resonance, exploring, as they are, the invisible vibrations and relations between people and plants and the things generated by the bonds between. Through this lens, For the Love of Bees expands its form, and becomes an artwork that ‘enables us to see our city as an energy system.’[94]

Conclusion

It began as a simple premise: a garden is an idea, a space and an action, wherever it take place.[95]

As Sarah Smuts-Kennedy and Monique Redmond’s collaborative and social-art projects attest, the garden is a fertile space – conceptually, metaphorically and literally, as both a subject, an art form, a quiet activism and a life practice. The garden and gardening is a way for artists to utilise their art practice to examine the challenges of our time. Gardening is both a thematic thread and a practice that enables an active response to contemporary politics and the specificities of place. Redmond and Smuts-Kennedy, though differently, might just be ‘Listening to the trees and the life of the land,’ as described by Sir Haare Williams.[96] In writing about Shopfront, Eccleston posits the garden as ‘a complex, cultural space rooted in the present. An actual, living, breathing space with its own internal logic readily expressing norms of socially generated experience, as well as the most private of desires.’[97] Generously giving their love and labour, they demonstrate alternative ways of being and moving through the world, where art practice, as a gardening practice, can be a productive and socially meaningful offering.

Bibliography

Barns, Sarah. “Arrivals and Departures: Navigating an Emotional Landscape of Belonging and Displacement at Barangaroo in Sydney, Australia.” In Creative Placemaking: Research, Theory and Practice, 56–68. New York: Routledge, 2019.

Barton, Christina. Towards a History of the Contemporary. Wellington: Victoria University of Wellington, 2018.

Bennett, Jane. Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Durham: Duke University Press, 2010.

Berthelsen, Chris. Artist interview, August 31, 2022.

———. “Distributed Resource Centre.” Mairangi Arts Centre, 2021.

Common Unity Project. “Common Unity: Together We Grow.” Accessed May 1, 2023. https://www.commonunityproject.org.nz/.

Demos, T.J. “Art after Nature: The Post-Natural Condition.” In Public Servants: Art and the Crisis of the Common Good, 343–55. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2016.

Eccleston, Tanya. “Notes on the Making of an Urban Garden.” In An Urban Quest for Chlorophyll, 14–29. Auckland: Rim Books, 2013.

“For the Love of Bees.” Accessed July 30, 2022. https://www.fortheloveofbees.co.nz/sarahsmuts-kennedy.

Heine, Zoë. “Making Like a Forest: An Interview with Xin Cheng and Adam Ben-Dror.” The Pantograph Punch, December 7, 2020. https://www.pantograph-punch.com/posts/making-like-a-forest.

Jansen, Dieneke, and Jenny Gillam. An Urban Quest for Chlorophyll, 2013.

Kai Rotorua. “Kai Rotorua.” Accessed May 1, 2023. https://kairotorua.nz/.

Kiddle, Rebecca. “Māori Placemaking.” In Our Voices : Indigeneity and Architecture, 45–59. San Fransisco: San Francisco Bay Area, USA : ORO Editions, 2018.

Letting Space. “Shopfront: Suburban Floral Association,” March 8, 2011. https://www.lettingspace.org.nz/suburban-floral-association/.

Loveless, Natalie S. “Practice in the Flesh of Theory: Art, Research, and the Fine Arts PhD.” Canadian Journal of Communication 37 (2012): 93–108.

Norman, Nils, Nina Folkersma, Taco/de Neef, and Jane Bemont. Nils Norman: eetbaar park = Edible park. Amsterdam: Valiz, 2012.

Public Share. “No NSense: An Antidote to Individualism.” Enjoy Public Art Gallery, April 2020.

Randerson, Janine, and Amanda Yates. “Engaging Publics: Art, Ecologies and the Urban Environment.” In Engaging Publics Public Engagement, 100–113. Auckland: Auckland Art Gallery and AUT, 2015.

Redmond, Monique. Artist Interview, January 11, 2023.

———. “The Event within Temporary Practices and the Public Social.” Deakin University, 2019.

Redmond, Monique, and Layne Waerea. “A Full Season [Daily News],” 2015. https://afullseason.wordpress.com/.

———. We Want Your Feijoas. April 2015. Social art. https://afullseason.wordpress.com/we-want-your-feijoas/_proposal/.

Robson, Sarah. “Shopping for Change: Busting the Supermarket Duopoly.” RNZ, July 18, 2022. https://www.rnz.co.nz/programmes/the-detail/story/2018849578/shopping-for-change-busting-the-supermarket-duopoly.

Roger, Melanie. “Richard Orjis, Walking in Trees,” August 15, 2019. https://melanierogergallery.com/news/2019/richard-orjis-walking-trees.

Smuts-Kennedy, Sarah. Artist Interview, March 6, 2023.

———. “Breathing In.” Accessed May 1, 2023. https://sarahsmutskennedy.com/.

Solnit, Rebecca. Wanderlust: A History of Walking. 1. paperback ed. London: Verso, 2002.

Sorensen, Jill. “Between Elsewhere and Away : Small Acts of Cohabitation.” Massey University, 2021.

Strongman, Lara. “Post-Disaster Gardening.” In An Urban Quest for Chlorophyll, 60–75. Auckland: Rim Books, 2013.

Tavola, Ema. “In Celebration of My South Auckland Garage.” Stuff, December 11, 2022. https://thespinoff.co.nz/society/11-12-2022/in-celebration-of-my-south-auckland-garage.

———. VV:Dua: The Story of Vunilagi Vou’s First Year. Auckland: Vunilagi Vou, 2021.

Weng, Amy. “They Covered the House in Stories.” Te Tuhi, 2021. https://tetuhi.art/art-archive/digital-library/read/they-covered-the-house-in-stories/.

Williams, Haare. “Kumara – More than a Vegetable.” In Our Voices : Indigeneity and Architecture, 15–19. San Fransisco: San Francisco Bay Area, USA : ORO Editions, 2018.

Zwartz, Hannah. “The Welcoming Committee.” Essay (blog), 2011. https://www.lettingspace.org.nz/essay-shopfront/.

Mikayla Journée (she/her, Pākeha) is an Auckland-based PhD Candidate and Graduate Teaching Assistant in Art History at University of Auckland. Her research is on the history of Social Art practices from Aotearoa New Zealand. Through contemporary case studies, her focus is on walking- and exchange-based practices and how these mediums are employed in the public realm as storytelling modalities to engage publics with place geographies, the more-than-human and memory. Her research interests draw on a professional background in Museum Public Programmes and activations in public spaces. Her work engages with Social Art Practices, Socially Engaged Art, Participatory Art, Public Art, Mapping, Geographies, Creative Placemaking, Indigenous ontologies, and New Materialism. Journée presented at AAANZ Conference (2022) on ‘chaos’ in socially engaged and participatory public art.

[1] See for example, Kai Rotorua: Kai Rotorua, “Kai Rotorua.” And the Common Unity Project: Common Unity Project, “Common Unity: Together We Grow.”

[2] Williams, “Kumara – More than a Vegetable,” 15.

[5] Loveless, “Practice in the Flesh of Theory: Art, Research, and the Fine Arts PhD.”

[7] The framework of research-creation in art practice comes from Natalie Loveless. See Loveless, “Practice in the Flesh of Theory: Art, Research, and the Fine Arts PhD.”

[8] Jansen and Gillam, An Urban Quest for Chlorophyll, 5.

[14] Randerson and Yates, “Engaging Publics: Art, Ecologies and the Urban Environment,” 100.

[15] Randerson and Yates, 100.

[16] Mere Roberts, “Mind Maps of the Maori,” GeoJournal 77, 2012, 747 in Randerson and Yates, 100.

[17] Randerson and Yates, 101.

[18] Nils Norman, 2016 in Demos, “Art after Nature: The Post-Natural Condition,” 654.

[20] Barton, Towards a History of the Contemporary, 16.

[22] Strongman, “Post-Disaster Gardening.”

[23] Placemaking came out of the US in the 1960s with Jane Jacobs, William H Whyte, and Kevin Lynch. Kiddle, “Māori Placemaking,” 45.

[27] Roger, “Richard Orjis, Walking in Trees.”

[28] Weng, “They Covered the House in Stories.”

[29] Heine, “Making Like a Forest: An Interview with Xin Cheng and Adam Ben-Dror.”

[30] Sorensen, “Between Elsewhere and Away: Small Acts of Cohabitation.”

[31] Berthelsen, Artist interview.

[32] Tavola, VV:Dua: The Story of Vunilagi Vou’s First Year; Berthelsen, “Distributed Resource Centre”; Berthelsen, Artist interview.

[33] Tavola, “In Celebration of My South Auckland Garage.”

[34] Public Share, “NonSense: An Antidote to Individualism.”

[35] The project description outlines that ‘People are invited to subscribe to receive a ceramic bud vase when they have a flower or a small bunch of blooms from their garden (or foraged) to display. The vase is given in exchange for two photographs: one of the flowering plant/shrub/tree; the second of the vase and flowers in situ. (100 vases for distribution.) BVS is a collaboration by Monique Redmond and Harriet Stockman. @buddingvasesubscription | https://www.instagram.com/buddingvasesubscription/.’ Redmond, Personal communication with the author.

[36] Redmond, Artist Interview.

[37] Redmond, “The Event within Temporary Practices and the Public Social,” 23; Redmond and Waerea, “A full season [Daily News].”

[38] Redmond and Waerea, “A full season [Daily News].”

[39] Redmond and Waerea, We want your feijoas.

[40] Redmond, “The Event within Temporary Practices and the Public Social.”

[41] Redmond, Artist Interview.

[43] Redmond, Personal communication with the author.

[44] Redmond, “The Event within Temporary Practices and the Public Social,” 38.

[45] Redmond, Artist Interview.

[46] Redmond, “The Event within Temporary Practices and the Public Social.”

[47] Redmond, Artist Interview; Redmond, “The Event within Temporary Practices and the Public Social.”

[48] Redmond, Artist Interview.

[50] Letting Space, “Shopfront: Suburban Floral Association.”

[51] Eccleston, “Notes on the Making of an Urban Garden,” 20.

[53] Jansen and Gillam, An Urban Quest for Chlorophyll, 10.Amery quest 10

[54] Zwartz, “The Welcoming Committee.”

[60] Norman et al., Nils Norman, 20.

[61] Demos, “Art after Nature: The Post-Natural Condition,” 351.

[62] Norman et al., Nils Norman.

[63] Demos, “Art after Nature: The Post-Natural Condition,” 351.

[65] For the Love of Bees at Griffith’s Gardens was addressing these issues specifically. Grayson Goffe, Artist Interview; Smuts-Kennedy, Artist Interview.

[66] Demos, “Art after Nature: The Post-Natural Condition,” 351.

[68] Robson, “Shopping for Change: Busting the Supermarket Duopoly.”

[69] Demos, “Art after Nature: The Post-Natural Condition,” 345.

[72] The polemic Demos is suggesting here is that for arts engaging with politics, ‘merely drawing attention to the problem is not enough.’ Demos, 346.

[73] Smuts-Kennedy, Artist Interview.

[75] Norman et al., Nils Norman.

[76] Demos, “Art after Nature: The Post-Natural Condition,” 354.

[77] Norman et al., Nils Norman.

[78] Demos, “Art after Nature: The Post-Natural Condition,” 354.

[79] Norman et al., Nils Norman, 21.

[80] Nils Norman in Demos, “Art after Nature: The Post-Natural Condition,” 354.

[82] Smuts-Kennedy, Artist Interview.

[84] Demos, “Art after Nature: The Post-Natural Condition,” 353.

[85] Norman et al., Nils Norman, 7.

[86] Barns, “Arrivals and Departures: Navigating an Emotional Landscape of Belonging and Displacement at Barangaroo in Sydney, Australia.”

[87] Demos, “Art after Nature: The Post-Natural Condition,” 353.

[88] Smuts-Kennedy, “Breathing In.”

[89] Smuts-Kennedy, Artist Interview.

[93] These ideas relate to Jane Bennet’s concept of ‘vibrant matter’. Bennett, Vibrant Matter.

[94] Smuts-Kennedy, Artist Interview.

[95] Eccleston, “Notes on the Making of an Urban Garden,” 15.

[96] Williams, “Kumara – More than a Vegetable,” 15.

[97] Eccleston, “Notes on the Making of an Urban Garden,” 15.

Mikayla Journée (she/her, Pākeha) is an Auckland-based PhD Candidate and Graduate Teaching Assistant in Art History at University of Auckland. Her research is on the history of Social Art practices from Aotearoa New Zealand. Through contemporary case studies, her focus is on walking- and exchange-based practices and how these mediums are employed in the public realm as storytelling modalities to engage publics with place geographies, the more-than-human and memory. Her research interests draw on a professional background in Museum Public Programmes and activations in public spaces. Her work engages with Social Art Practices, Socially Engaged Art, Participatory Art, Public Art, Mapping, Geographies, Creative Placemaking, Indigenous ontologies, and New Materialism. Journée presented at AAANZ Conference (2022) on ‘chaos’ in socially engaged and participatory public art.