Elizabeth L. Pence

The artist Laura Fritz grew up in a planned community called Park Forest near Chicago, a place that appreciated strong examples of architecture. Designed by developers Philip Klutznick, Nathan Manilow, and a city planner named Elbert Peets, it was built in 1948 and helped settle the lives of demobilized American soldiers returning from WWII. Fritz attended the art department at Drake University, working in a studio arts building that was close by Meredith Hall, a building designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, built in 1965. With its proportions and clean structure, the horizontality of the building with its vertical windows is striking viewed any time of year, in snow or the bloom of spring. The day-to-day relationship to the structure formed an impact on Fritz’s aesthetic, as they ultimately realized that their table design was influenced by the minimalist design of van der Rohe.

Pulling the thread of an aphorism for which Ludwig Mies van der Rohe is known, ‘Less is More,’ a statement that came to define the utopian ideals of modernist design and architecture, reveals many sources in a patriarchal lineage that lie further back. He did not originate the phrase or principle, but it’s associated with him, through his ‘effective’ use of it. ‘Less is More,’ is attributed to Peter Behrens, a pioneer in German industrial design, who drafted the 20-year-old Mies to work on aspects of the AEG Turbine Factory in Berlin between 1907 and 1910. There are prior examples that occur in Robert Browning’s 1855 poem, Andrea del Sarto, in Shakespeare’s play Hamlet, (as ‘brevity is the soul of wit,’) and ‘entities are not to be multiplied without necessity’ was part of a commentary made by the Irish Franciscan philosopher John Punch in 1639. William of Ockham posited in the mid-fourteenth century, “Plurality must never be posited without necessity,’ and it’s also connected to the ancient Greeks, such as Aristotle and Chilon of Sparta, through idiomatic translations.

Relationships that artists develop in their practice between object, action and meaning are generative inquiries, often into liminal spaces and Fritz’s work operates at this site of threshold. They apply pressure to the certainty of meaning and know where these edges are, liminal territories with room to create a series of challenges through her objects, videos and installations that reorient the viewer to engage rather than consume and ultimately dismiss the experience of art.

Fritz’s garden is part of their studio, where they develop ideas and test them, “I observe the systems of the natural world and mix what I observe in the garden’s natural systems with the imposed systems that humans try to exert over them. My process is empirical and improvisational; planning is involved, and I allow the process to develop as it will, given the material attributes, and so on. I then decide which elements are the right ones to use and make accommodations.”[1] They cast specimens drawn from these botanical elements, manipulating the casting process to further mutate and expand the forms, presenting them in a completely different context in the gallery.

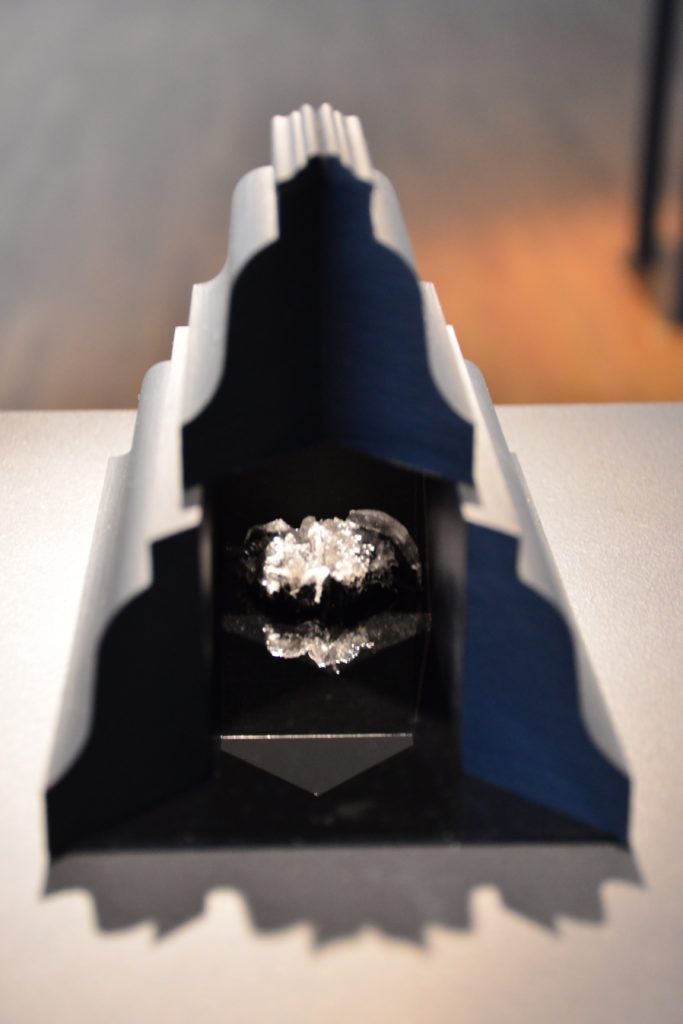

Ornamentation in Fritz’s work is oriented towards the use of light, expanding the visual character and estranged beauty of the cast polyester forms of works like Ingress, (2013) or Specimen A038, (2019), which lies inside a small enclosure whose structure evokes both Victorian and gothic revival architecture and references the dome-shaped structures found in Buddhist shrines called stupas. Protecting it from handling and removed partially from view, at their 2019 exhibition at the Portland Art Museum the work was sited in a large space with soaring ceilings. A spotlight focused on the work, directing the viewer’s attention to the table. There were limited viewpoints of the cast form, with its unusual presence, beautiful and troubling at the same time.

Laura Fritz, Specimen A038, (detail with housing), 2019, Wood, plexiglass, resin. Image courtesy Elizabeth L. Pence.

Laura Fritz, Specimen A038, (detail with housing) 2019. Wood, plexiglass, resin. Image courtesy Elizabeth L. Pence.

‘I’m interested in the light itself and how it can influence the viewer’s perception. It can highlight and draw attention in a certain direction, obscure, or even become a sculptural material. It can also influence expectations, such as making the subject seem imposing or vulnerable. When a piece is lit from within, such as the video installations Convocation, or Alvarium II, (both works 2019), or some of my cast objects that catch light and glow, the subject then appears to almost have a life of its own. It becomes something we might feel the need to watch out for and could make us feel more vulnerable in the space.’[2]

The objects and video works build situations that cue the border of perception, directing a participatory response in viewers. Mounted on the wall, the sliver of plexiglass mirror within the vertical work, Sconce II, (2019), harbors such a thin reflection even when looking directly into it that it remains unstable, difficult to locate visually. As one walks past, it catches the corner of the eye, drawing the viewer back to investigate the intriguing work, as if something moved. The black molding exterior has a rich, muted palette like the housing of Specimen A038. Fritz explores the peripheral, things that exist at the corners of our perception. Their work raises questions about what the focal point actually is, and whether the viewer can trust their perception.

Laura Fritz, Sconce II, 2019, Wood, plexiglass mirror, 29.25″ X 4.5″ X 4″. Image courtesy Elizabeth L. Pence.

Constructing the works with a lean, purposeful aesthetic, Fritz developed different iterations of their video sculpture, Alvarium. Using footage of honeybees projected within the hive-like form, Alvarium 1 (2016) was installed at the University of Oregon Portland campus in 2016, suspended inverted from beams that Fritz designed with the building’s architecture in mind. In video that was shot of hives used in the study of Colony Collapse Disorder at the Oregon State University Honeybee Lab while working with Dr. Ramesh Sagili, Fritz used a projection of the patterns of bee movement in the work, the natural motions that bees use to communicate and forage, using an unknown language. Giving the appearance of a hive indoors, as if isolated from its natural surroundings. Fritz stated that the work emphasizes the bee’s precarious position in the world and how, “as species, we rely on each other in ways that aren’t fully understood. We often don’t see their grand, coordinated efforts, and I wanted to show how an entire hive responds, so I captured one collectively responding to a disruption (something the lab does to study and care for the bees regularly). At first it seems chaotic and then they organize themselves into what looks like continents. The bees are incredibly active and purposeful.”[3]

Fritz says that, ‘in my work overall, I contrast the controlled aspects of design with organic elements, such as the movement of bees or a murmuration of birds, that may appear to be chaotic, but adhere to a different system, one that is not man-made.’[4] Alvarium 3, was in the August 2023 group show, Biomass, curated by Jeff Jahn in the historic Maddox Building in the Pearl District of Portland, OR. Adjacent to pandemic recovery, it was emotionally, critically and logistically important, an anchor for a reinvigoration of this area of the Portland art scene. With a large group of emerging and mid-career artists working in painting, sculpture, photography and new media, the show’s sharp curation was a response to a conversation with the eco-economist and urbanist Lark Lo Sontag, who is the inaugural Sadie Alexander Economics Fellow at The New School for Social Research in New York and was timed with the Animal Behavior Society’s convention in Portland. Fritz exhibited Alvarium 3, (2023) alongside Transposition, (2005/2023) wood, acrylic, video projection, a 2005 work upcycled with 2023 video technology. Placed on the ground, a black-painted box with an opaque, acrylic window is brightly lit from the inside. As one looks at the frosted window of the box, the shadow of a cat moves across it. The presence of the animal occupies the box so convincingly that the viewer wants the cat to be let out. But the box is not a container with a live animal trapped inside, rather a projected image of a cat, marking the absence of the figure with its replacement as a representation. The nature of the work unsettles both sculptural and filmic space when viewed either as a container with a live animal inside or as a filmic device, and pivots on the perception of the viewer, trading on the terms of three-dimensional and two-dimensional space, juxtaposing reality and artifice.

Including sculpture in their practice brings engineering skills and an increased specificity to her intentions through a broader range of material means, where she makes interesting relationships between gorgeous and unnerving.

Laura Fritz, Convocation, 2019, Wood, reflector array, video. Image courtesy Elizabeth L. Pence.

Foreground: Laura Fritz, Angular Wall Piece, 2019, Wood. Background: Laura Fritz, Convocation, 2019, Wood, reflector array, video. Image courtesy Elizabeth L. Pence.

Convocation, (2019), is a matte black pentagonal, chimney-like structure that occupied its own room in their solo exhibition at the Portland Museum of Art, and projects swarming images onto the walls as five round pairs at varying levels. The video is on a twenty-minute loop edited so that it flows together, with what looks like insects at first, then becoming slightly larger like birds, and as the swarms move closer into view reveals that it is a murmuration of birds. The footage is of Vaux swifts that roost by the thousands in Chapman Elementary School’s unused chimney each September in Portland. This unusually large swarm of birds convenes in an urban environment and has adapted to it. Fritz says, “the flickering motion and light focus the viewer’s attention upon the relationship between their movement and the confines of the space to bring about curiosity and empathy in the viewer regarding their situation. The contrast of natural and humanmade highlights the animals’ vulnerability and response, subsequently evoking ours.”

Fritz seeks to catalyze curiosity and evoke responses involving unease and attraction. Placing natural systems within or around unnatural settings and destabilizing easy consumption by the viewer, Fritz applies pressure to the certainty. They infuse the object with energy through material appeal, yet the works avoid the neutrality of pure aesthetics or formalism because their conceptual framing orients the object away from procedure or narrative, and specifically positions them as a series of unmoored entities which generate sublime experiences. This stress on anti-narrative creates uncertainty, which is a more active and vibrant intellectual state, and is also the space of change. Fritz has developed a praxis which takes viewers along on an uncanny adventure that they normally wouldn’t have access to. They observe the behaviors of animals, birds and insects, and of viewers as they interact with the works, establishing the viewer as an element, a participant in the experiment.

[1] Laura Fritz interview from August 2016 on the art blog, Anti-Heroin Chic.

[2] February 2020 interview between Fritz and Brian Libby of the website Portland Architecture.

[3] Laura Fritz interview from August 2016 on the art blog, Anti-Heroin Chic.

Elizabeth L. Pence is an artist and writer who lives and works in and is from, the San Juan Islands of Washington State. They have written articles and reviews for the Los Angeles Review of Books, artUS and Artweek. They graduated from Santa Monica College of Design, Art & Architecture, and the California Institute of the Arts, where they worked as the Institute Review Advisor from 2001-2005. Included in group exhibitions in Los Angeles that were curated by Karen Finley, and George Herms, which included the work of Mark Bradford. They are a recipient of a Durfee ARC grant for the exhibition, ‘Cleaning Up,’ curated by Lisa Tan, which included Charles LaBelle and Francis Stark. They have lectured on painting at the Orange County Museum of Art, taught photography at The Armory Center for the Arts, and worked at Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions (LACE).