Adam Ash Barbu

Recorded on April 26, 2023

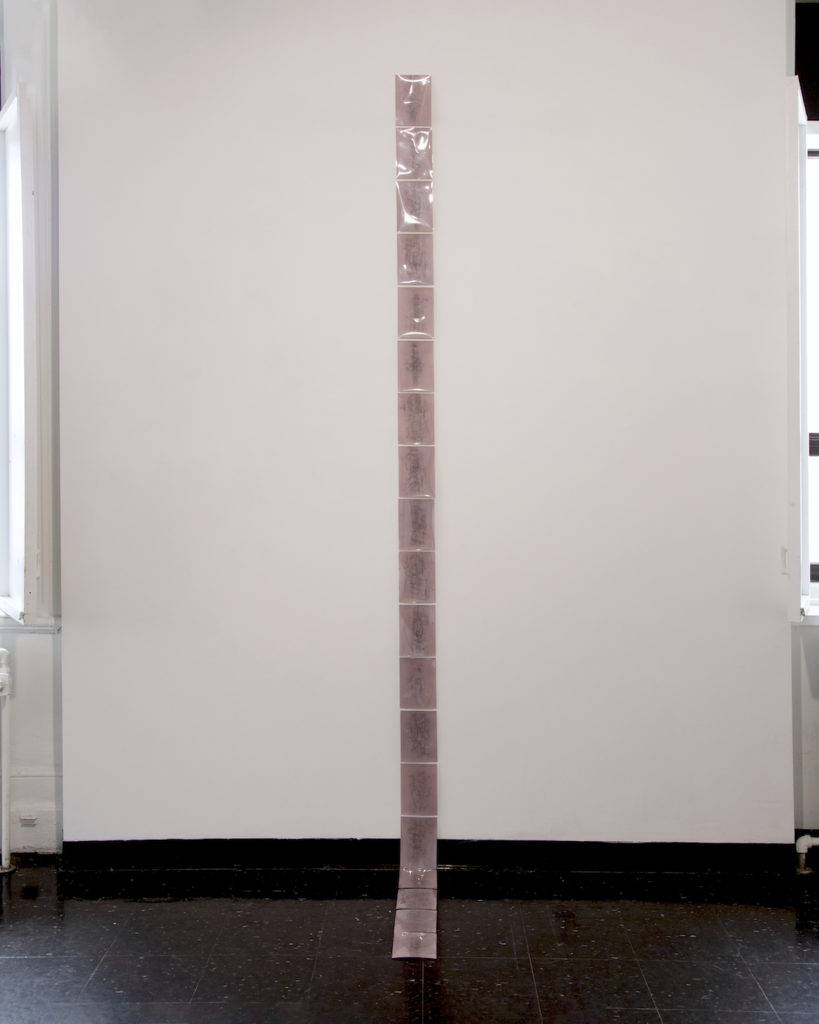

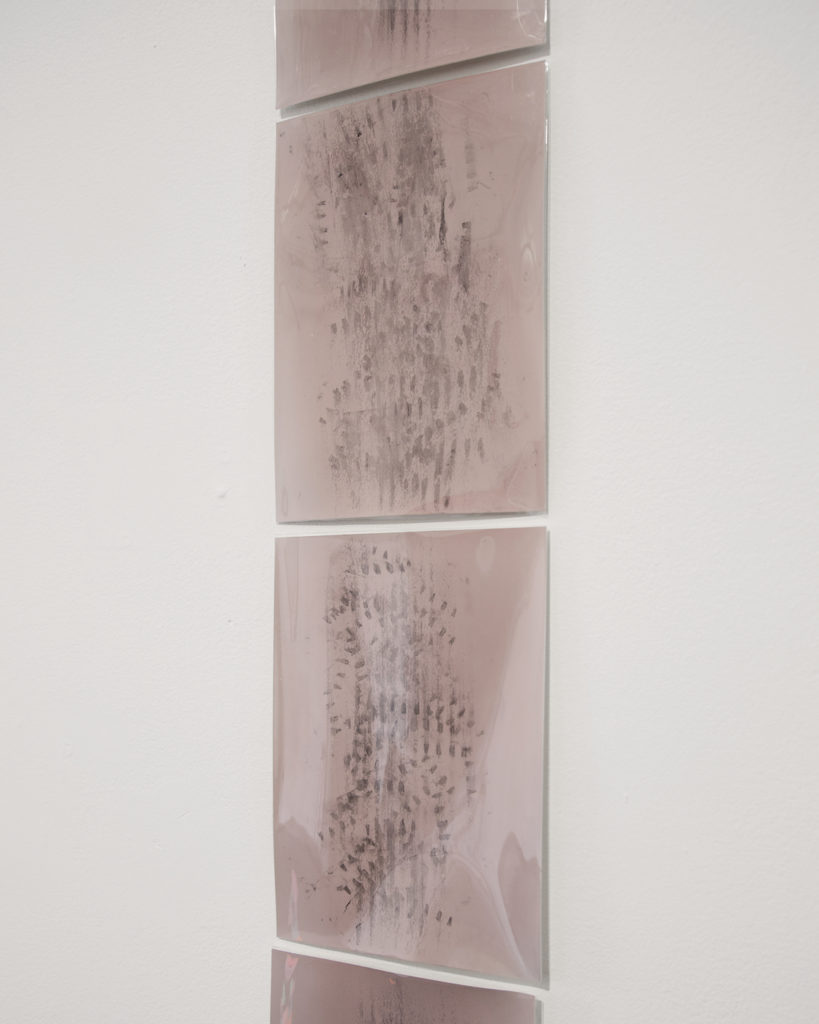

Neeko Paluzzi, ‘Vada, of polari’, from: Words Unsaid: Autobiography and Knowing, curated by Adam Ash Barbu, 2023. Image courtesy of the artist.

In this recorded and edited dialogue, independent curator Adam Barbu and lens-based artist Neeko Paluzzi explore questions of postmodern authorship and queer narrative agency by turning to the diaries of the late filmmaker Derek Jarman (1942-1994). Reflecting on the resonance of the diaries in their past and present work, Barbu and Paluzzi consider entangled ecological, political, and bodily relations that offer expansive definitions of self-portraiture. Between 1989 and 1994, Jarman recorded nuanced observations on art and life through daily journal entries documenting his garden at Prospect Cottage in Dungeness of Kent, England. Spanning 1989 through 1990, the seminal text Modern Nature (1991) was composed following Jarman’s HIV diagnosis at the height of the AIDS epidemic in Great Britain. With entries dated from 1991 until his death in 1994, Smiling in Slow Motion (2000) offers a continuation of that earlier archival project. Both collections illustrate Jarman’s multifaceted gardening practice alongside his changing health in a world marked by extended crisis. This article, “Modern Nature” and the Self-Portrait, is the first chapter of a series of dialogues that Barbu and Paluzzi will create in response to Jarman’s timeless, genre-bending writings.

Adam Ash Barbu: Returning to Derek Jarman’s diaries for the first time in several years, I’m drawn to the story of an individual who appears in a supporting role. How might we frame the relationship between Jarman the filmmaker and his lover Keith Collins, also named “Hinney Beast” or “HB” in the writings? HB is a complex figure whose identity remains opaque. He serves Jarman’s vision for the garden. He never speaks. Yet he is a central to the narrative.

Neeko Paluzzi: More than a mere companion, I find HB to be both a character and an object. Jarman writes about him as if he were another plant in the garden. This is not to say that HB is denied of his autonomy, as we learn of his frequent travels beyond the horizon of Prospect Cottage. In these moments, Jarman worries about and misses HB. Following a period of absence, he will return to the text and resolve the narrative. Early April, 1989: “When HB arrived in the evening he brought me out of my depression. I’m so confused by what has happened that I’ve forgotten whether it was today or yesterday. But in fact it was today.”[1]

AAB: And the story of Jarman’s life ends with his presence. The final entry in Smiling in Slow Motion, dated Birthday 1994: “HB true love.”[2] These are, presumably, the last words Jarman wrote, a few weeks before passing at the age of 52 due to an AIDS related illness. The line offers a sense of closure to the reader. But what does it mean to speak of the narrative agency of HB? If Jarman is the caretaker of his garden, then HB is the caretaker of Jarman. In this way, the diaries do not serve to exalt Jarman’s singular artistic vision as a master gardener. We find that the artist is dependent on some other force.

NP: I wish I could say I was this optimistic. Perhaps it is because I read the diaries as extensions of Jarman’s films. I’m conscious of how he plays with fact and fiction and thus begin to wonder: At what point is he curating reality by creating characters of his relationships? As an artist who explores auto-narratives in my work, I begin to fantasize about what, precisely, is perceived as real in the diaries. Perhaps we access something like truth in the hospital scenes in the second act of Modern Nature. The relationship between Jarman and HB feels most real in this context. It is also a time when Jarman was the most broken down, physically and mentally. Still, there are entries that invite necessary skepticism, where Jarman cultivates HB as a character-object. I feel this tension in the scenes where HB arrives to help edit film.[3]

AAB: In the act of composing the diaries, we might imagine Jarman sitting at his desk, recording his thoughts at the fall of each day. But perhaps these writings are not what they first appear to be. January 29, 1993: “For me there is little rest, the fires are tended, the floors washed, the beach combed, breakfast cooked and this diary written.”[4] In the Vintage Classics edition of Smiling in Slow Motion, an untitled photograph by Jarman accompanies the entry. Here, an open notebook and fountain pen sit before a cloudy window overlooking the garden at Prospect Cottage. The objects are placed at a perfected angle to achieve maximum compositional effect. It is an absurd, staged reality that verges on the cinematic. Elsewhere in the text, we happen upon a seemingly candid image that captures Jarman examining packaged food in an American supermarket. And another where he leans on a balcony railing, glancing at the camera through one eye, dressed as a hooded prophet. What is at stake when we read the diaries as an expansive self-portrait that creates space for “personal mythology” to grow?[5]

NP: Jarman is a skilled editor. This brings me to the sense of montage that connects across his films. Images aren’t shown at random. And I can see it in the writing. He leaves visual clues—that we are headed towards a religious motif, for example. He might refer to the symbol of the snake and several entries later he is writing about the Madonna in his film The Garden (1990)[6]. Given this narrative play, it is plausible he knew he would write about certain subjects beforehand. Or perhaps he has gone back to self-edit the diaries to help the reader prepare for the eventual scene. As we have discussed at length during past projects, I believe that fiction is potentially more real than what is commonly referred to as “stream of consciousness.” To edit one’s story is deeply human. We have the ability to recall the past and think about the future in the present. Therefore, those memories and visions should impact the way we construct auto-narratives. June 24, 1989: “I only go to the cinema now out of friendship or nostalgia. I cannot watch anything that is not based on its author’s life.”[7] Later, July 19, 1989: “Why do people read novels when they are only written in the hope they’ll be made into films?”[8] I can’t help but think he is doing this very thing—that he believes these diaries also operate as films.

AAB: Near the end of his life, Jarman considered the diaries through the lens of theatre. December 2, 1993: “Off to Brussels to see the play of Modern Nature, it was very well done. The actor, Chris, was compulsive viewing. I think we should organize it for Edinburgh.”[9] A few passages later, the entry before his last, New Year’s Day 1994: “Howard and Sarah are off to London. The play is doing well in Brussels.”[10] Thus, he concludes the archival project by suggesting, with little subtlety, that the diaries are acceptable, complimentary, even satisfying as a dramatization. He permits the diaries and the performance to be read as interchangeable.

NP: Jarman is an artist who made his career by interpreting and fictionalizing the lives of others. The thought that life might end through the dramatization of his own story would, I think, be fulfilling.

AAB: In the films, he has rewritten biographies that range from Saint Sebastian to Ludwig Wittgenstein. April 15, 1989: “The terrible dearth of information, the fictionalization of our experience, there is hardly any gay autobiography, just novels, but why novelise it when the best of it is in our lives?”[11] How to decipher this entry? Regarding the question of autobiography, Jarman knows that fiction and non-fiction cannot be so easily disentangled—that these categories are not simply at odds.

NP: July 11, 1989: “Our name will be forgotten in time / And no-one will remember our work / Our life will pass away like the traces of a cloud.”[12] Jarman knows that his work will live on, at least temporarily. He was blessed to have found critical success through his art. This is, for me, a wink and a nod.

AAB: November 12, 1989: “Today brought another film crisis shoot. Should I carry on? I decided not—but know I’ll wake up tomorrow morning and change my mind. I’m being very silly playing little lost boy.”[13] If, through the diaries, Jarman is playing with the fiction of his life, then the garden exists as the ecological, political, and bodily context for this for this story to be carried out.

NP: May 14, 1989: “Dungeness has luminous skies: its moods can change like quicksilver. A small cloud here has the effect of a thunderstorm in the city; the days have a drama I could never conjure up on an opera stage.”[14]

AAB: And there are actors in this imaginary diaristic film. This queer community of humans and nonhumans—that is, his friends, the plants, and the flotsam he collects from the shore of Dungeness—activate the narrative. They each possesses a symbolic significance, reaching from the living past and leaning into possible futures. For example, he reads the daffodil, Narcissus, as a sign of resilience. It is a flower that stands up straight up against the cutting wind of early spring.[15]

NP: Or the poppy. Jarman writes that the poppy is a flower that likes to grow in turned earth—“newly disturbed soil.”[16] And here are diaries in which the artist is digging up his past, becoming and unbecoming different versions of himself on the page. We might read this metaphor through The Wizard of Oz, which he later references.[17] At the heart of these writings is a constructed image, a clouded self-portrait, that is simultaneously real and imagined. Yet even considering the changes to his body and the landscape, he remains in control of the narrative. The garden is itself a space of control. Otherwise, it would be the wilderness. In the Western imagination, the wilderness is an artistic motif of Romanticism. It is that sense of moving into the continent, into the mountains, and finding oneself. I think about the search for the blue flower, a symbol of longing and sexual awakening for so many queer people. In creating this juxtaposition between the garden and the wilderness, he lays bare questions of modernity and the discontents of progress itself. It is no accident he chose to live at Prospect Cottage, a cabin that is quite literally not in a forest. Here, the artist stands with his flowers upon a bleak shingle plot against the backdrop of the nuclear power station. Jarman is highly aware of these contrasting symbols.[18]

AAB: It is also the case that, for Jarman, the garden shouldn’t look perfect, with packed borders or tight arrangements that borrow from colonial traditions. January 1, 1989: “In this desolate landscape the silence is only broken by the wind, and the gulls squabbling round the fishermen bringing in the afternoon catch.”[19] The garden should appear sparse, weathered, and “natural.” And it remains curated as if a set design. On the subject of the curatorial, one question that emerges is that of care.[20] Certainly, to care for something involves compassion and sensitivity. But to care for something is also to control it.

NP: I’m interested in care as a function of time. In the diaries, care is framed in and as a slow process of aesthetic worldmaking with fragments of material and symbolic significance. We are speaking of artistic research in terms of means as opposed to ends.

AAB: Early December 1991: “The filming not the film.”[21]

NP: In Modern Nature, we are offered a montage of scenes of a film of his life written diaristically, as opposed to a linear autobiographical narrative defined by struggle, redemption, and self-discovery.

AAB: He offers groupings of hundreds of individual scenes that democratize life as it is experienced affectively. Observations are charted by calendar date. Sometimes, a day is granted a line. Sometimes, a day commands several pages. The diaries are constructions of immeasurable overlapping, shifting, and fluid narratives. Notably, Modern Nature concludes with an entry that documents a mundane shaving ritual. Reflecting on the body in advanced illness, Jarman writes about sudden weight loss and the slowly changing texture of his skin.[22]

NP: The visions of his mother and father are given the same weight as writings that document planting cycles. It is almost as if he’s blinking. And now he’s somewhere else. There is no quantitative measure of duration between one moment to the next—the legible marking that a certain sequence was harder to move through. While the diaries illustrate the complications of living with HIV, moving in and out of the hospital, there are few scenes in which I notice him struggle psychologically. But there is an exception. He strains during interviews about his work conducted by the press. February 22, 1989: “Yesterday I was subject to a barrage of questions for nearly seven hours without a break, my head spinning like a child’s top.”[23] An interview is an ordered dialogue in search of some confessional truth. Thinking through the question of fiction in self-portraiture, I find this resistance compelling.

AAB: How does Jarman use language to resist restrictive definitions of queer identity? In the diaries, he explores colour not to describe what he sees but how he sees. I think of it as an invitation to the reader.

NP: I sense he draws upon descriptive colour to guide the hypothetical scripted version of the diaries we have been referring to. It is the central point of emphasis in his storytelling. The story, in other words, is in the description of colour. Here, I begin to understand why someone would want to use colour in their work. And that is a profound for me. As an artist who works primarily in black-and-white, I have struggled with the perceived superficiality of colour. That a daffodil is yellow would seem obvious. Previously, I would have felt the need to strike it from the sentence. I held the belief that when we remove color, we see without distraction and beyond seduction. Remove color and I can understand the depth of your work. But a garden without colour is not a garden. A garden is superficial in its beauty. And it is also a matter of weaving connections between human and nonhuman beings in space. Colour, for Jarman, adds that feeling of depth as both processes interact. Further, colour is uniquely subjective. Working with you. I didn’t realize that you were colorblind. It is possible that none of us are experiencing colour in the way that an artist might have intended.

AAB: There is a certain objectivity in the daffodil’s yellowness. But as you suggest, Jarman uses colour to honor the depth of his lived experience. The garden is a “symphony” that breaks apart the binary opposition between the universal and the particular.[24] Colour is forgiving to difference. It is simply open.

NP: In the entry dated March 22, 1989, Jarman writes about an intimate homosexual experience in his adolescence coupled with the desire to keep potted violets in his bedroom. Later in the passage, his grandmother expresses concern, sharing that violets are associated with death. They are bad luck.[25] This passage reveals the ways in which colour operates intertextually. With certain references, I begin to feel a space around me that connects across bodies, across histories, through both creative and destructive forces. For the reader, colour is an enveloping force. It fills your head. And like the attraction to water in the desert, it is also a mirage. My connection to violets undergoes a transformation when Jarman draws this connection to mortality.

AAB: Working together on my recent curatorial project Words Unsaid: Autobiography and Knowing (2023), you developed the series Vada, of polari (2023). The installation consists of 19 dying photosensitive silver gelatin prints presented in a vertical stack. Each of the papers contain stamped, dragged, and smudged patterns of the word Vada, which translates from the coded queer language Polari as “see.” In the gallery space, filled with natural light, the pages transformed, turning a muted violet. This is the first time I have seen you work in colour.

NP: Years prior, near the time we first met, I began working with similar prints as a response to Jarman’s work, particularly the film Blue (1993). During our time collaborating on Words Unsaid, that earlier project felt unfinished.

AAB: We share this feeling. I find it difficult to quote Jarman in my work. As you know, I have tried to write about the diaries before, specifically addressing the question of the garden as a metaphor for queer embodiment. Without fail, these projects have failed. On the one hand, I have combed through the finest details, wishing to uncover some hidden aspect of his identity. On the other hand, I have scanned the writings, focusing on structure and syntax to retain some overarching account of character development. And I have arrived nowhere and everywhere. I can’t locate myself in the writing.

NP: He refuses to make it clear what is more or less important in the narrative of his life. This is perhaps the reason why we feel lost. The diaries are too porous. Modern Nature is not simply a postmodern autobiography about an artist’s garden and his struggle with HIV. He connects his artistic practice to personal histories, political discourses, ancient mythologies, and the works of Ovid, Faust, Goethe, and Berlioz, to name a few. Focusing solely on the garden as queer body, we’re missing the other turns of the Rubik’s cube.

AAB: To respond to the diaries in our future work, we should begin with the question of personal mythology—with the limits of autobiography as a reflection of truth. Jarman’s garden is more than a literary context from which beauty grows against all odds. At Propsect Cottage, he pushes and pulls into a space of illusion. It is a stage where fiction and non-fiction are entangled, irreparably so.

NP: November 11, 1989: “I water the roses and wonder whether I will see them bloom.”[26]

AAB: He continues: “Even so, I find myself unable to record the disaster that has befallen some of my friends, particularly dear Howard, who I miss more than imagination.”[27] Jarman often contrasts the garden as a site of refuge with the heaviness of life as is lived beyond the horizon. In fact, he refers to his two lives, the one in Dungeness and the one in London.[28] Tending to the needs of his plants, building the garden installation, the consequences of his actions are different. The reality is that his friends are dying and he is dying. And he misses Howard more than he could ever recreate on stage. What does it mean for art and life when we miss something more than imagination? To honor the gravity of the situation, Jarman is unwilling to narrate that loss. It is too much—beyond representation, beyond the scope of the work. When such unimaginable tragedy strikes, the sequence breaks.

NP: It is too real. This is his living, breathing paradox. And we can almost see in a moment the film stopping.

Neeko Paluzzi, ‘Vada, of polari’, from: Words Unsaid: Autobiography and Knowing, curated by Adam Ash Barbu, 2023. Image courtesy of the artist.

[1] Derek Jarman, Modern Nature (1991; reis., London: Vintage Classics, 2018), 217.

[2] Derek Jarman, Smiling in Slow Motion (2000; reis., London: Vintage Classics, 2018), 387.

[3] Jarman, Modern Nature, 154.

[4] Jarman, Smiling in Slow Motion, 302.

[5] Jarman, Modern Nature, 23.

[9] Jarman, Smiling in Slow Motion, 385.

[11] Jarman, Modern Nature, 56.

[20] This definition of curating sources from the Latin cura, which translates to English as “care.”

[21] Jarman, Modern Nature, 201.

Neeko Paluzzi (he/him) holds two masters degrees from the University of Ottawa: a Masters of Fine Arts (2022) and a Masters of Film Studies (2013). In addition, he is a graduate of the Photographic Arts and Production program at the School of the Photographic Arts: Ottawa (2017). He was the recipient of the Karsh Continuum Photography Award from the City of Ottawa in 2021, had a feature exhibition at the Scotiabank CONTACT Festival in 2019, and was the winner of the 2018 Project X, Photography Grant from the Ottawa Arts Council. Paluzzi currently teaches English at the Official Languages and Bilingualism Institute, University of Ottawa, Canada.

Adam Ash Barbu (they/them) is a writer, curator, and educator based in Ottawa. They hold an M.A. in Art History from the University of Toronto and were a recipient of the Middlebook Prize for Young Canadian Curators. In 2022-23, they were the Guest Scholar-in-Residence at the University of Ottawa’s Department of Visual Arts. Currently, they work as a Research Fellow at Visual AIDS, New York. Barbu has lectured on topics in queer theory and curatorial studies locally, nationally, and internationally. Recent writings have appeared in publications that include Peripheral Review, Esse art + opinions, Canadian Art, and Journal of Curatorial Studies.