Greg Minissale

All images by and courtesy the artist.

Aaron Obeek is a sculptural and ceramic artist from Ōtepoti/Dunedin, who graduated in 2021 with a BVA from Dunedin School of Art. His work has always been informed by the natural world: the body, mind and the landscapes around us. The first work he created with clay was a small pinch pot shaped like a disgruntled head. He found a connection with nature and a therapeutic process working with clay he hadn’t felt with any other medium.

Suture Peel Mask, 2021, Clay, Orange Peel, Thread.

This connection and exploration into art as a therapeutic process during study led Aaron to working on the range of clay heads, and masks made from orange peel stitched together. These works formed my installation Concentrate, Concentrate (2021). Which featured the 12 individual clay and porcelain heads on precarious looking stands, giving presence to the space by watching the viewer and making them more aware of the way they interacted with what was around them.

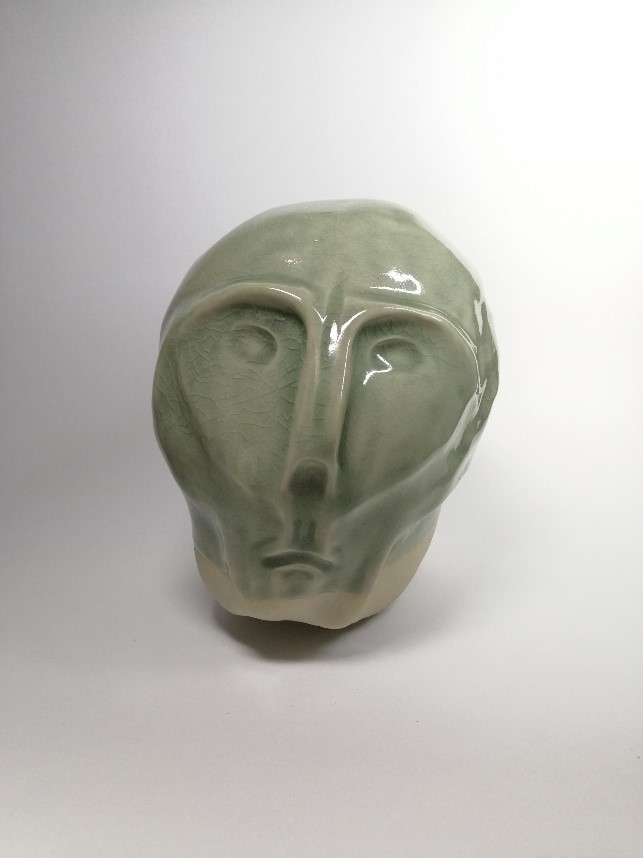

As his practice evolves and changes, creating works featuring heads and faces will continue to be a major kind of form for works that tell a story. Aaron would like his works to look almost human, as they are confronting, or emotive, to everyone in a unique ways.

Greg Minissale: Were you always interested in creating three-dimensional objects or did you start with painting or drawing? I am trying to get to the root of the haptic and manual impulse in you: creating with touch and texture?

Aaron Obbeek: From as early as I can remember, I have been more drawn to creating in three dimensions than two. We would make masks and tube towers out of paper on rainy days or when it was nice to spend a lot of time walking in the native bush near home, or by the ocean exploring rock pools. That connection between touch and texture, interacting with nature, is what I want to feel when creating. I have always enjoyed painting and drawing but never felt a great connection to either, creating an object feels like a more natural way for me to tell a story or convey a feeling.

GM: With interviews it’s always difficult to establish “the beginning”—such delicate things; but also because of the notion of whakapapa: how a particular tradition one is born in might have led somehow to a sensitivity to music, or mathematics or medicine, etc. There is always an element of speculation in this. I always associate my interest in art with my Italian background and the emphasis placed on the manual tradition of particularly expressing with the hands. Do you feel that touch, hands, and creating objects that are the product of touch and the hands, somehow are tied in with your whakapapa, or the earliest images or sensations you can remember? Sorry to get primordial with this, but why not? We are exploring the wellsprings of creativity together…

AO: Descending from two migrant families that arrived in New Zealand in the 1960’s, I believe those ancestral notions of living bleed into all generations. With few ties to our heritage, I have always felt somewhat cast adrift and at once at home in New Zealand, being the only country I’ve really known. The Scottish idea of ‘The right to roam’ has always stuck with me. I think that connection to nature and creating from what little is available comes through in my own work, as well as a strand of humour which is a strong connection I have from that side of my family.

Perhaps the other side of my heritage, Dutch, in some way has contributed to me being drawn toward ceramic works. I think of creativity and thinking outside of the box when I think of the Netherlands. As a country that relies not only on the tides, but has created canals and water in their daily life, I feel a large part of this has contributed to my affinity for water, and perhaps this shows through in some of the appliques I give to works.

Blue B #2, 2021, Porcelain, Celadon Glaze.

GM: Dutch ceramics are beautiful, particularly blue and white. And art has no borders, no? Let’s move on from discussing early influences to artistic ones. Which artist or potter (do we still use that word?) has had the greatest impact on your visual style, overall aesthetic techniques, or even subject matter?

AO: Exactly, art has no borders and is and always should be accessible to everyone. During my time studying, a close friend encouraged me to learn more about Anicka Yi, whose work I love. That connection between scent and memory, I believe, has more lasting power than an object on its own. It feels more transportive and immersive.

In terms of sculptors and ceramicists, looking again at William Moore over the last few years, I have vivid memories of seeing pictures of his work as a child, which I found interesting having that memory of work returning after so long.

New Zealand in particular has such a wide range of ceramicists that have encouraged me to work with clay in less traditional ways. I am always been blown away by Chris Weavers work, the attention to form and detail that flows into functional pieces.

GM: For those not familiar with the artists and makers you have named, could you please inform us about what these artists and makers are famous for—what imagery or subjects did they deal with, and why are they important for the formation of ideas about your present projects?

AO: Relative to the pieces I’ve made that are figurative: heads and masks, some artists that have informed my own practise are Henry Moore, a British sculptor that was prolific through the 1930’s to the 1960’s. Many of his sculptures are carved stone abstracted figures with limited facial features. The carved pieces utilise the negative space to allow light to cast shadow and give movement to the works. Animal Head (1951) is a plaster-casted work by Henry Moore. With its hand polished finish, it looks like a large bone carving of a bizarre animal skull grinning. I appreciate the way he takes inspiration from symmetry and curvature in nature – shells, bones, the body, and then creates something so unique and instinctive that it still looks like it has come from the earth.

Zoe Leonard is an American artist whose sculptural work: Strange Fruit (1992-97), explores mortality and loss, change over time through a sculpted form. Zoe Leonard used 295 different fruit peels that were repaired and stitched back together and sealed. The way the stitched works are re-formed leaves hollows and gaps. They seem to have an echo of life in them but are a solemn tribute to the losses of the AIDS epidemic. The way fruit has dried over time reveals colour and textures of decay, dimples, and darkened tones. The stitching of the works was also a therapeutic process for the artist, who repaired and mended the peels and processed grief through this process.

Anicka Yi is a South Korean artist who creates sculpture and olfactive scents to work alongside the pieces. We Have Never Been Individual and Biologizing the Machine (2019),

Are incredible figurative forms, reminiscent of glowing cocoons created from kelp and an acrylic coating. The forms are rounded and curved, polished and smoothed, and from a distance look like the outline of a head or a body glowing in mid-air. The way Anicka Yi studies and brings natural form into their work is beautiful; there’s always a tinge of hope for technology and nature joining and overcoming the climate crisis.

Lastly, the ceramic pieces that New Zealand potter, Chris Weaver, creates are another beautiful example of work that meets the symmetries and angles of nature to make works with personality, a story, and a figure. Prolific in making functional teapots and sets, that are also sculptural forms. His way of giving the works a textured and natural finish meant for touching is generous. I always try to consider how my own ceramics will feel when touched or held by someone, and I try to get that sensation of it feeling natural as well.

GM: What is it about heads that you find intriguing? Animal or human? Is there something primordial in this interest?

Ceramic Works

AO: I have always been interested in the uses of masks, in history and pop culture: why and how they alter someone’s character. They can create a shield between the wearer and reality in a way, similar to the way people project and curate their personality through a mobile phone now.

I was a big Star Wars kid, and remember being absolutely terrified of Darth Vader and the Stormtroopers. The way some mystery can conjure an idea of us being scarier or stronger than we really are, until you see the human face beneath and realise the wearer is no different from you.

I like the emotive aspect of creating heads or masks, the way an expression can be captured and relayed. And the way everyone who looks at a sculpture of a face sees something different, or it speaks to them individually

GM: So how have you actually technically created the heads in your work? I assume most of them are clay? There is this old tradition of seeing clay as a metaphor for matter which the divine breathes into (pneuma) in order to create life.

Repeat Peel Mask, 2021, Clay, Orange Peel, Thread.

AO: These works were all created with clay or porcelain, the majority of the orange peel masks were created for sculpted heads made from clay so that I could manipulate the peel into holding its shape even when standing alone.

I find clay extremely helpful to work through creative blocks, in a similar way to automatic drawing but in three dimensions, letting the mind have a rest and the hands do some making. I find this works well in a therapeutic way, to let the mind wander and formulate new ideas.

I enjoy working with nature as a medium. I often wonder at the significance of coming from the earth and returning to the earth in death. The superstitious side of me ponders whether traces of the past linger in and imbibe the natural world around us. I think all artists leave a small part of themselves in their work, specifically with clay, much care and effort goes into rendering it to a quality that can then be made into something new.

GM: Very interesting. I’ve never considered the tactile quality of letting the hands wander and automatism in clay. Of course, you need to work the clay so it doesn’t have any air bubbles in it that would make it explode in the kiln. As I remember, this is a methodical, but rhythmic process. I wonder if sometimes you see faces in the clay, like some people see faces in clouds? A way in which the unconscious is always forming face gestalts. And the glaze accentuates the features of the head?

AO: Working the clay in a similar fashion to kneading dough. I’ve always felt quite automated during that process, as well. Focussing on only the dough/clay, to ‘feel’ if the consistency is right, with clay we eliminate air by wedging it repeatedly on a hard surface. Before adding form and shape to a ceramic work, I look for facial features in the way it has naturally formed. It can feel like the clay is giving me direction to what it should already look like. When working the clay on a bust stand, I usually use paper as a base to hold the shape as I work it, I go for a reasonably plain head-type shapes before applying clay over the top. Then I let patterns the clay forms, draped over the paper base, inform me how the head will become.

In some way it can feel like seeing what the work will become but through touch: the way the clay feels, how malleable it is, and whether it is ‘behaving’ and doing what you expect it to.

GM: How do you feel when the head is complete and has its own independent existence staring back at you?

AO: It can be rather haunting. I feel somewhat responsible for them in a way but am also realistic about them being just an artwork to other people that may see them.

It is cathartic seeing them finished, as well. I often feel like I’m processing grief as I work in a similar way to Zoe Leonard through Strange Fruit. Mortality, and the face we see, do not always match the underlying personality.

I like to think I’ve made the works spirit resilient enough to deal with whatever the future holds, even if they outlive myself.

Aaron Obeek is a sculptural and ceramic artist from Ōtepoti/Dunedin, who graduated in 2021 with a BVA from Dunedin School of Art.

Gregory Minissale is a Professor of Art History, specializing in global modern and contemporary art and critical theory at the University of Auckland.His books: Rhythm in Art, Psychology and New Materialism (2021) and The Psychology of Contemporary Art (2015) are both published by Cambridge University Press.