Nicole Perry

The Ulumate Project: The Sacredness of Human Hair centred around the Fijian custom of wig ceremonies in times of mourning.

Nicole Perry: Daren, would you mind telling us a little bit about yourself to begin with?

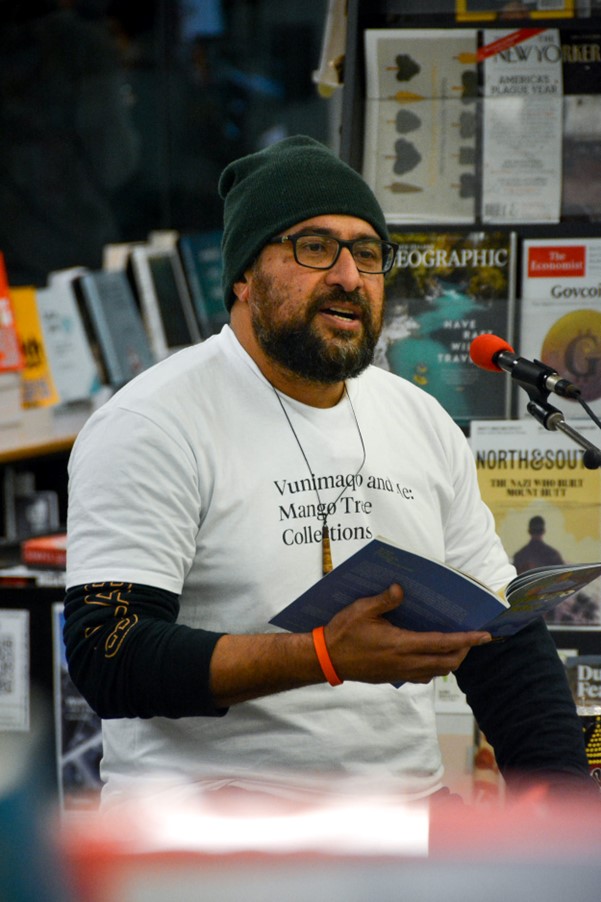

Daren Kamali: Yes, Ni sa bula vinaka, kia ora from New Zealand. Thanks for having me. I’m Daren Kamali, and I’m a poet and multimedia artist.

This Ulumate Project has been going since 2013.

Ulumate in Fijian is “dead head” or could be a “wig” as well. The generic Fijian term for wig is ulu tha vu, and there’s three of us that have been working on this project since 2013, since I started at the Auckland War Memorial Museum and first discovered that there was a tradition in Fiji concerning the head and around [the] making of a wig with coconut sennit and hibiscus stem which is vau.

And yeah, I was really intrigued by it. I was going to cut my hair back then and take it back to the Islands and bury it and plant a coconut tree on top of it like most Islanders do, but then I saw this, and it really resonated with me, and I wanted to continue. At the time, I was going to cut my dreadlocks after 17 years, and I thought, okay, I’ll start collecting my hair and eventually make a ulu cavu wig like I saw at the Museum.

And yeah, so it’s 2023 now, and we’ve done a few exhibitions, and yeah, we’re sort of building on that kaupapa around the head and the hair – human hair.

NP: That’s really interesting, so you’ve taken something that’s from the Islands when you’re saying that it’s typical to – maybe not typical – but it’s considered a state-of-being or something to do to go back and bury your hair? Is that what you were saying with under a coconut tree in Fiji?

DK: Well, it’s a tree that you plant when you bury your hair, and yeah, most Islanders plant a coconut tree on top of it. From different Islands, not just Fiji. And yeah, so I was aiming for that and then this really changed the whole look of my art as well as my vision for what I was going to do with the ulu cavu, Ulumate Project.

NP: And why would you bury your hair? For a Palagi [white person] who knows nothing about this, what would be the reason or the cultural practice of burying your hair?

DK: Well, the head – the hair, is a very sacred part of the body, especially for Fijians. All around the world and in the Pacific, but especially for Fijians during that era – that time, and yeah, we love our hair; we love grooming it, and it’s sacred like I said, it’s tabu, and we’d like to bury or keep it. Some people do keep their hair as well. Yeah, I don’t know if that answers your question.

NP: No, that’s good, that’s good. Learning from colleagues and friends of mine who are Māori, that it’s very important to have the placenta buried where the iwi is, and that has that sort of idea that the home and the connection to home is through the placenta, and the placenta being buried with the iwi, so I wonder if that’s something similar with the hair, to that extent.

DK: Very similar, yes. My boy’s placenta, pitopito, has been buried and my younger boy’s under a banana tree, so, yeah, he can have multiple dreams when he grows up, and my other boy has his pitopito buried under a pōhutukawa tree. So, yeah, it’s similar to that as well.

NP: The project has been running for about 10 years, and so you had those dreadlocks going on for a very long time, as you said.

DK: Yes. So, I cut my dreadlocks, after 17 years of growth – and that was 2014, and since then, I’ve grown my hair again, cutting it only twice after that. So that’s been 25 years’ worth of hair that has become a contemporary ulu wig. After 250 years of being dormant and not practised. Yeah, it’s really an honour to be the one to present this practice in this day and age. In these contemporary times and to bring back the forgotten.

NP: This is wonderful. I have seen you present at Lorne Street Library (Auckland Public Library) when you were talking about this contemporary practice. Can you tell us a little bit about the historical practice and the importance of the ulumatu and the hair and the wig?

DK: The ulumate wig used to be…only men wore those wigs. It was made out of coconut sennit, which is magimagi, the inside of it, so it’s all padded together with coconut sennit and plaster hibiscus fibre, which is called vau, that is like a string that holds the whole thing together and with strands of hair and cotton – so the dreadlocks are hanging and then that was 17 years’ worth of my hair, and then the top of it is 8 years’ worth of my hair sort of put together by the heritage Fijian artist named Joana Monolagi. She’s from Serua in Viti Levu.

NP: You’re making a historical practice contemporary, what was the historical sort of use with the ulumate?

DK: Yes, the ulumate practice was, yeah…In mourning, they would cut the hair beneath, they would make the ulumate from their hair, plus the hair of the enemies from war as well, and then they would make it into a wig, and then they would wear it until the hair underneath grows back. Normally, that’s 100 nights, and we call it bogi drau in Fijian, and that’s still practised today, and bogi drau means the 100 nights you give up something that you really love…back in those days it would have been kava or coconut cream or fish or something that really was…loved and also, yeah, you would wear that wig for the 100 nights – sleeping, waking and yeah, doing stuff till your hair, grows back. It is a mourning period.

NP: So, it’s a mourning piece – so when someone passes – that’s when the hair would be cut and woven, and it would then be worn.

DK: Yeah, worn and worn into battle. Many worn by warriors.

NP: Into the battle as well. So, almost having that mana of the people that had been defeated before that, going into the battle, again.

DK: Yes, definitely. Fijians were…yeah, really into that practice as well, and they believed that the mana of their ancestors or their enemies’ actually becomes theirs and then yeah, it continues…

NP: …continues on…. Going back to your practice and how you started – so you said about 10 years ago you decided to cut your dreadlocks after about 17 years – how did you become inspired? What led you to start this practice?

DK: I actually cut it…wanted to cut it in time…I was doing my mourning process as well. I had just broken up with my second boy’s mum. Yeah, it was really hard for me, but then I was working at the Museum at the time and I met one of the Na Tolu members who got me the job. His name is Ole Maiava, and he was the one who showed me this particular work, and we started talking about what the practice was behind it, and it just sort of resonated right away for me because I was going through that sort of feeling at the time and I was like “wow,” I really want to do this so yeah I cut my hair then I started growing it again just to get enough…I didn’t know who was going to make it, how I was going to make it because I didn’t know how to make it. It hadn’t been made for over two centuries, so I had to look around.

At the time, Creative New Zealand had asked me to bring 5 Indigenous artists, [Fijian – Taukei] artists, from Fiji who practises the old crafts. One of them was a costume-maker as well, but she had never practised putting ulumate together, so, yeah, it was still hard for me. We spent a couple of years together, and then Auntie Joana showed up to my second hair-cutting ceremony, which was at the Auckland Central Library in 2018, and then it was there she asked me in Fijian: “Just let me know if you want me to make your ulumate.” And I’m like, “man, yes please, I’m like Auntie please yes, thank you, can you?…” And since then, I’ve combed and collected my hair. For 8 years, I kept on collecting my hair that I combed or cut, and I put it in plastic bags, and yeah just took it over to her in 2020 during lockdown, and I gave it to her in those bags with my dreadlocks, and it stayed with her for over a year, and then she called me in 2021 just before New Years day and said, “yes, when are you going to come back and pick it up? My husband is saying when are you coming to pick your hair up? It’s been laying here on our kitchen table for ages, and it feels like somebody is always in our lounge.”

NP: So, you’re always present, so to speak. And this was back in Fiji?

DK: No, this was here. In Joana’s house. Yeah, and love to her husband. Rest in peace. He passed away last year, and yeah, he was there right through the process. Her and her children. It was a special process too. And I was waiting for her to call me, and she was waiting for me to call her as well until…she contacted me, and then I was like: “Okay, I’ll come pick it up, thank you.”

NP: So, tell me a little more about Auntie Joana.

DK: Auntie Joana Monolagi, she is…she came here in the 60s. She’s probably one of the early Fijians to come to New Zealand with her husband. I think they came in the late 60s, and she’s been here since then. But she’s from a village in Serua, in Ba, which is on Viti Levu, on the west side…She practises not just ulumate but did the revival of the Veiqia Project, which is the Fijian tattoo project, and they work on that with only women, because only women used to wear those tattoos and practise that. She’s a masi-maker, a tapa-maker as well, so she does a variety of traditional Fijian art, and she’s just amazing to be on board with Na Tolu for the Ulumate Project.

NP: She sounds like it, for sure. Bringing these arts from Fiji over to New Zealand, has she found difficulty with that? Or has she found it to be a very welcoming, sort of situation?

DK: She’s also a very strong Christian – a very strong Catholic woman, so it’s very hard to find people that are like that who still have the Church as well as practising old traditional crafts and things like it. So, I think, yeah, it has been a bit hard for her, especially with the Church, but she just takes it in her stride, and she’s just amazing in the way she believes in herself and her art and sort of gives reverence and acknowledgement to our ancestors as well as the current – the Most High – God.

NP: So, she’s the one that does the weaving of the ulumate?

DK: Yes, she did the ulumate itself. Yeah, she did everything on the ulumate, so she’s the maker. We got a second book coming out in August, and it’s going to highlight her making of that as well as photos that we’ve taken by this guy called – what was his name? Francis Herbert Dufty. Back in the 1800s, he did a photo shoot of Kaicolo warriors – 3 of them – that were wearing those wigs, and so…’cuz Ole does all the photography, so his concept was to do a repossess, repose of those records of those photos. So we’ve done one with Na Tolu, and I’ve done one with my two sons as well, so it’s a 3 thing, and it should feature in the book coming up.

NP: I did see the photos you posted on your Facebook of you and your sons recreating this scenario, and how was that for you? How did that feel for you as someone having been in this space now for 10 years working with your hair, working with the weavings and passing it on to your sons at that time?

DK: It’s really special. Apart from me, only my sons are allowed to wear the Ulu cavu wig, and that was a very special shoot and it was a bit emotional for me to have my boys and watch them grow and just become young men and normally those are the young men that wear the wigs back in the day as well. I had to explain to them too, being born in New Zealand and brought up here, but they’ve been home to Fiji a few times, and it was very special, and I’m looking forward to actually blowing it up and framing it for my mum. She wants a copy as well.

Yeah, then I did a shoot in Fiji as well with Aunty Joana and the apprentice Eramasi, that I mentioned earlier, under the mango tree where I grew up in Fiji. So that’s a special place. So different places in Fiji, we did a couple of shoots, and those were the places where I grew up my first 17 years before coming to Aotearoa.

NP: That’s absolutely amazing. So walk us through a little bit about the protocol with who can wear it and who cannot in most cultures and its very set in protocol who can wear one and who cannot. It’s very clear you have to be gifted one. You can’t regardless if you’re Indigenous or not, you do not just rock up and put on a headdress. It has to be gifted to you, and it has to be worn with honour. Is that something similar with the ulumate?

DK: Yes, it’s definitely something like that. You need permission, and normally, it is from a village called Nakorosule village, and it’s up from the Naulucavu clan or mataqali, those were the people who used to wear it and practise that back in the day. It’s normally given to your sons during that time, like I said. It stays within that line.

Of course, you need permission to wear it or even to touch somebody’s hair or head. Especially in Fiji because that meant really dire consequences back in the day – ending up in death. Just like Mr Baker – Reverend Thomas Baker – who tried to take a comb from a chief’s hair…so they were good friends, but the warriors didn’t really like that so, yeah, his boots are still in the museum in Fiji. They tried to cook his boots. They thought boots were meat as well.

In saying that, we went to Cambridge – they’ve got 8 ulucavus in their collection, and while over the 2 days, we were researching and examining these ulucavus, the curator offered me to try, if I wanted to, wear one of those wigs…and I was shocked by that actually. Just being asked to wear one. And Ole was taking photos, and he was looking at me, and he was like, I think he was thinking the same thing too…I sort of just said, “can I think about it?” And then, yeah, I’m still thinking about it. I would never…

NP: And the person who offered you this…because this actually starts to talk about very interesting ideas about colonial spaces and decolonising these spaces, and it’s actually a very big problematic if the person who is in charge of the museum doesn’t understand these sort of protocols. How did you react to it?… How would you tell this person? Because I know that sometimes being forthright – it’s not something that’s done either, right? So how would you portray to this individual that this is actually not protocol or this is not acceptable?

DK: I had to take some time and think about it…cos she was the curator, she was like…you know, she offered…and I was like…I hadn’t even thought about wearing one of those. And I wouldn’t wear any of those. It’s out of respect as well because it wasn’t mine, and the thing is we also don’t know actually who wore it and who was the keeper of that wig, and like I just told my friend, “oh, I think if I had worn that, I would be dancing on the ceiling that night time.” The ancestors would come and visit me for sure.

DK: I don’t know if I’d come back to New Zealand the same person or not. [laughs]

But yeah, we got through it, and yeah, I just told her…she said, “oh you think about it,” and I said, “oh, thank you,” and “I’ll think about it.” So, I never really answered the question for her.

NP: And that takes some understanding too.

When the question is not answered – that kind of means no.

DK: Yeah. And then I respected her too. She was a mate. She welcomed us into the Fale, into the museum. Yeah, that was the first museum where Von Hügel collected the Fijian artefacts, not just the ulumate, but also the likus, which are women’s skirts and stuff. So that’s how he started Cambridge Museum. He said he wanted to be the curator, and he wanted to start with the Pacific collection, which was the Fijian collection.

NP: Wow, I didn’t know that history or legacy with the Cambridge Museum that it started, not only in the South Pacific, but in Fiji. It’s quite remarkable as well.

DK: Yeah, cos he was collecting there in the 1870s, and then he came and started the museum, yeah.

NP: And you said he had 8 of the ulumate there?

DK: I think that’s the one museum in the world that’s got the largest collection of ulumate. Cos in Fiji Museum we only have 6 in the collection. And there was actually nine, and one was already placed on a statue – a Solomon statue – which I think they thought was Fijian was iTaukei. Thus, it was placed on him…we had said to leave him so he’s in the back and he stays there with his ulumate – his particular ulumate, which is the hidden one.

NP: This is the Solomon with the…Fijian…

DK: The Solomon Islander with the Fijian ulumate. Which is not a rare thing. It might have come from that way, I think. Maybe like New Caledonia because they do a lot of hair practices out there as well.

NP: Speaking about hair practices then, and going back more to the Fijian perspective, are there any sort of hair practices that are Fijian in origin? Or is the ulumate one of the more common ones?

DK: Yes, so, ulumate is for the men, and they call it Tobe pronounced – tombe for the women. So virgin plaits are the tobe, and when you see women wearing the tobe you know oh, she’s not married yet, and until she gets married she would cut the tobe. But before the tobe, before the hair practice, there was the tattoo/Qia and until Christianity took away the tattoo, then we started to do the hair practice with the Fijian women.

NP: Interesting. In Germany, I’m not sure if you’ll find this interesting or not, with the dirndl – the dress that the women wear at Oktoberfest – depending on the way the woman ties her apron tells everyone if she’s single, married, or available.

DK: That’s the one, yes. And also with a flower…I think in the Islands, the woman wears it (maybe) on the left side, I think, then she’s single, and if she wears it on the right, she’s married – she’s taken. It could be the other way around, but it’s something like that.

NP: So, with your Ulumate Project, you’ve been to Cambridge, you’ve spent time here in Aotearoa, and in Fiji. Where else have you taken your project?

DK: Yeah, Aotearoa – I think there’s 4 at Auckland War Memorial Museum, and there’s about 5 in Te Papa Museum in Wellington, with a tobe , so a tobe in Wellington as well – a female, virgin plait. I was explaining to the curator that this is a Fijian practice as well. A female version of the hair practice.

I’ve just come back from Fiji again. The second time. We went to see the ulumates in the Fijian Museum. We were in Cambridge, then we went to Horniman Museum in London. There’s one there. But I think within London alone, even at the Reeves and the British Museum, in around all those museums within the UK, there would be over 2 dozen in their collections of ulu cavu in various spaces. I know there’s one in Ireland. I know there’s one in Norway. And I’m still looking at Germany, of course. Holland. And in all those other European countries as well. Australia. Melbourne’s got something Perth has got something. Those are the ones left to look for. Bishop Museum in Hawaiʻi has got something there. Smithsonian has got about 5 ulu cavu collections there. Harvard Peabody Museum’s got one.

It’s all over the world. We try to make a database of the ulu cavus around the world and eventually be published.

Wig, Fiji Islands, bleached human hair – Pacific collection – Peabody Museum, Harvard University.

NP: Wonderful. That’ll be such a valuable contribution. You were talking about your experience in Cambridge and being offered to wear an ulumate which wasn’t your own, when you see these different collections, and the way that they’re displayed, is there a different feeling that comes across you? Is there a different feeling when you see these things that are so far removed from where they belong?

DK: Yes. Yeah, I know what you mean. When I see some ulu cavu like that. I really don’t know, I can’t really explain the feeling. I get a bit overwhelmed but also very excited and nervous at the same time, I guess. Especially when I went to Cambridge and they said, “Oh, don’t worry about wearing the gloves. You can do it with your hands.” And I’m like “wow, even if it’s for study, we have to wear gloves,” and stuff like that. Yeah, so just the difference in those little approaches to handling and those different spaces, which is very exciting. But to see an ulu cavu in real-life is just…it’s a masterpiece, and it’s something…for me, I automatically pay reverence and respect to the ancestors. It brings that feeling, I guess, back…from the old to the new again.

NP: I like that. Speaking of that – the old to the new – with your practice and your work, it’s the new to the next almost. What’s the next sort of phase for you with the project? So you’ve spoken about your sons and passing this on to your sons in Fiji, and in Auntie Joana framing it for your mother as well, what’s sort of the next step or vision for the project for you?

DK: Na Tolu is working with at the moment with an art gallery here in Auckland – Objectspace[insert hyperlink: https://www.objectspace.org.nz/exhibitions/the-ulumate-project/]. We’re putting a plan together for the next couple of years. We are wanting to visit other places in New Zealand, or even internationally and take exhibitions to those spaces responding to Ulumate Project. So when we went to Fiji in April this year, we went to an exhibition with the BlueWave artist from my Oceania centre in USP [University of the South Pacific] in Fiji, and we’ll be selecting probably a handful of artists to exhibit with us in May next year in Fiji to respond to our Ulumate Project and what their responses are. These are amazing artists from our community in the Islands. Also, we would like to visit places like the Smithsonian in Washington DC and Bishop Museum in Hawai’i, and the Peabody Museum in Harvard. Yeah, go to those places where the ulumate are. And then take our ulumate and have talanoas- talks- and exhibitions, and publications of our research and revival in multimedia arts.

NP: Wonderful. I think you know that’s where a lot of my passion and my heart lies as well with looking…with my work on Germans and this Native American image, and artists who reclaim and reappropriate that. The work you’re doing, it’s just so important and so essential. This revival. And just telling and showing Palagi people that, “you know what, hey, this is very cliché, but we’re still here. This is still going on, and this is still a practice that is embedded in our ancestors, embedded in ritual, and is still moving forward.” I think it’s so important that you’re doing this project.

DK: Thank you, thank you Nicole, and I also wanted to say that it would be lovely to bring those taongas home. But I want to say that those museums really look after those taongas – iyau the Fijians would say. Ulumate – and its certainly got facilities to look after it and they’re looked after really well, so when we go do our research and revival art projects, we really…tell them thank you for looking after our ancestors’ taongas (although you took it from our place). [laughs]

NP: Yeah, that’s always a contentious thing, isn’t it? Those are things people are still trying to wade through and figure out. But it’s good to hear there are positive things in those spaces as well, and not just ideas of things being taken and removed, but also, okay, thank you, you’re honouring our taonga, but maybe there will be a time when it comes home.

DK: If it was still in the Islands, most of it, after colonisation and Christianity was introduced, most of it would be burned or destroyed.

NP: And that’s the other side of it, right? Yeah, and it gets problematic and contentious for different reasons as well. There is that acknowledgement that if these taonga weren’t removed that they would have been destroyed. Native American totem poles, for example, they were meant to go back into the ground. They weren’t meant to stay forever. But then being removed to other places is also very problematic because they’re supposed to be in the land they came from, you know, so it’s very interesting. It’s a different way than what white people are saying…me, for example, now being in Paris and looking at the Louvre, watching all of these people look at the Mona Lisa, right, and it’s just meant to stay there, whereas a lot of art is meant to go back into the earth…you know, which is very different from Western conceptions of things and consumption of things.

DK: It’s like pottery in Fiji…still finding 2,500-year-old pottery laying around in the swamp and stuff like that. This was practised mainly by the highlanders in Fiji. So those people up in the highlands – the hills and the mountains. Christianity first touched on just around the coastal areas, so these guys up there weren’t really “tamed”, I like that word, till after, way after. So that’s what happened when missionaries had to go up there, and…that’s what happened to Reverend Thomas Baker. He was supposed to go back to England, and he said, “no, I’ll do one more mission so I can go and see, I can change these guys.” And that’s what happened. These guys were very different. They have their own luna, they live off freshwater and the forest, and also, they don’t see the ocean until they’re 20 years old.

NP: Wow, I didn’t know that. Talking about Reverend Baker again, so I learned from a friend of mine, she’s German and had a child with a Samoan man. He’s 8 or 9 now. When I first met him and her properly in Auckland, probably about 2016, I happened to rub him on the head, and she just looked at me and goes, “no, you can’t do that.” I found it quite interesting as a German woman saying that. But that Samoan practice of you don’t touch the head, you don’t touch the hair, which I thought was quite interesting, that seems to be something that’s throughout the Pacific region?

DK: Yeah, and especially in Fiji in the old times and even today. I guess anybody because you just don’t go to anyone to cut your hair. You’ve got your hairdresser. You’ve got somebody to touch your hair. And that was the same with the chiefs in Fiji. Even the warriors don’t touch their body or touch their hair. They’ve got their own hairdressers, and permission is the main thing. Unless you get that permission and then you touch the hair, it’s a blessing. Otherwise, it’s really a curse. You’ll get into trouble.

NP: Understood. He was just the right height to control him by head. To move him around, make sure he’s going the right way. It was my fault, but okay, I couldn’t reach his shoulder, he was too small.

DK: But I guess it’s a playful thing in sports nowadays. Especially the rugby and Sevens and stuff. You see men just touching each other’s hair because they’re overjoyed. But still, yeah, sometimes we forget the sacredness of the hair and the head.

NP: Exactly. Especially if it’s not in the dominant culture that these sorts of things need to be respected, that gets forgotten in the high of the moment, I guess.

DK: That’s what happened to Baker. He was really high in the moment. He was a good friend of the chief, and he was a good man, but then he didn’t see.

NP: Shifting focus briefly, tell me about Ole and his role in this project.

DK: So, for us, Ole is the moment-capturer. He’s the one who does all the photographs and tries to capture the moments that we have, especially the special moments we have in different museums and places and shoots, and bringing back the forgotten and reposing of photos. Aunty Joana is the ligatabu, which means sacred hands, so normally, I found this out when I went to Fiji, normally, those people who make the hair and stuff, they don’t use their hands during the time. So it takes a week or two weeks, they won’t use their hands. People will serve them and yeah, their hands are made for what they are making and the craft, and Fijians call them the ligatabu, which is the sacred hands of a cakacaka ni liga the working of the hands, you know. So those are the two positions that they capture, and I’m the subject. I just do what I’m told. [laughs]

Daren Kamali is a Fijian-born New Zealand poet, writer, musician, teacher and museum curator. He holds a BA from Manukau Institute of Technology and a Masters of Creative Writing from the University of Auckland. In 2008 he co-founded the South Auckland Poets Collective, a youth program focusing on poetry as an agent of change. A former recipient of the Fullbright-Creative New Zealand Writer’s Residency, Kamali has held numerous fellowships. Toegether with Ole Maiava and artist Joana Monolagi, Kamali has been presenting research on The Ulumate Project: The Sacredness of Human Hair centered around the Fijian custom of wig ceremonies in times of mourning.

Nicole Perry is a Senior Lecturer in German and Comparative Literature at Waipapa Taumata Rau| The University of Auckland in Aotearoa| New Zealand. Her research interests include Indigenous artistic interventions in German/European culture both in North America and the South Pacific; travel writing; and visual culture. She is also the associate editor (German) for the William F. Cody digital archives project, based out of Cody, Wyoming.