Gregory Minissale

Duchamp’s Fountain began as a rather ordinary object—a urinal—in a mundane and anonymous context. It was then taken out of this indifferent continuum and ‘placed’ into the realm of art where it became an ongoing event. According to Deleuze, the naïve understanding of the eternal return posits an original from which copies are made, continually repeating time through the mode of representation. This repetition also implies a repeater: in another model, time is experienced by a present, phenomenological “I” through whose linear progression of sense experiences time is marked. The first part of this essay examines why these two models of time and experience lead to rather circular and unproductive art historical analyses, especially of Duchamp’s Fountain, where the notion of an original is irrelevant, and where as a concept, it continues to resonate in difference. The last part of this essay shows how Deleuze’s affirmation of difference as a principle of time and becoming supersedes these models, and opens the way to a living diversity of artworks that engage with Duchamp’s Fountain by challenging the blockages of regress, repression and solipsism inherent in the notion of repetition.

The traditional notion of representation which underlies much art historical method tends to identify an original (reality, identity or concept) which is repeated by the representation or series of representations thereby valorizing repetition. Deleuze’s concept of difference places an emphasis not on representation but on the actualization of difference or differences. In this way, each ‘urinal-event’ the artworks which refer to it do not repeat an original so much as unfold an ongoing multiplicity of new problems and solutions. Several scholars have allowed us to look at the productivity of individual artists, Gerard Richter, Mary Kelly and Leonardo da Vinci, for example, fruitfully developing Deleuze’s difference and repetition in order to show how art actualizes becoming in many forms.[1] Instead, I will look at a number of artists’ works, rather than an individual artist, which form a collective intensity with Duchamp’s Fountain within a larger complexity of difference, one which now spans almost a hundred years from the date of the Fountain, 1917, to the present.

Nietzsche’s eternal recurrence which Deleuze rechannels into his philosophical project is not one of simple repetition. The thought experiment of the eternal return posits a recurrence of becoming, a circle (or a loop) which encloses (or ties off) difference from what lies outside of the loop or circle, which is sameness. The eternal return leads to a plurality of these loops or actualizations of difference giving a richness and depth to the world.[2] For Deleuze, Nietzsche affirms difference in itself, his eternal recurrence of every event is a continual becoming. This is quite different from the Platonic notion of transcendent Ideas eternally recurring in history in the form of debased copies or representations, an attitude which has dominated our view of works of art as representations.

Each of the works of art that I will examine here positively actualizes difference as an intensity in itself, an event which may involve an individual who does not, however, constitute the event in its entirety, for this event has connectivities in time and with other events. This difference should not be defined negatively as a lack of sameness. For Deleuze, organisms are sites of transformation through which these differences are actualized, and the art work becomes the site of an event, challenging the restrictive formulation of a repeat representation and disturbing repetitions of habit and memory trapped in a succession of lived presents. Thus both representation and individuation have to be rethought in our encounter with art. Art does not mean the encounter of a viewing subject with a representation, both these terms are undermined by Deleuze, for the ‘I’, the self, is disseminated “in a field of forces and intensities and individuations that involve pre-individual singularities.”[3] These pre- and post-date the ‘event’ of art, and partly constitute that very event.

The belief in cyclical time and Neoplatonic thought depends on identifying structural and formal qualities in a work of art, psychology, society or period and is essentially supposed to lie underneath any surface differences these aspects of human existence might suggest. These underlying structures are usually valorized as indications of essentially defining features which repeat in history. All instances of time are conflated into one, ‘original’ occurrence whose configuration is not only seen in all its copies but is brought back to life again through these usually inferior replicas. It creates a method of interpreting the world and events intent on seeing repeats, and referring back to an original blueprint whose essence can be found as a subtext or undisclosed quality or pattern which the priest, art historian, psychologist, neurologist, anthropologist or gatekeeper digs up, in order to discover the ‘true meaning’ of an instance of timeless wisdom or evolution.

Examples of this belief in recurrences as a form of explanatory strategies of the present may be seen in religious exegesis based on a sacred time recurring in the seemingly mundane, itself disguised as chimeras, bodies, veils, vessels, reflections or even works of art. Much of this hermeticism is based on the tradition of Platonic forms, or Plotinian emanationism, and extended by the Renaissance system of analogies. In Mircea Eliade’s recurrence of myth, archetypes are structured as signifying chains such as moon-sea-pearl-woman, or fire-voice-spirit-purification-cooked, and are reborn with rituals or redescribed in art and literature which become the handmaidens of hidden presences.[4] And in Freud, we compulsively repeat the past, our conscious lives can be seen and understood by the recurrence of syndromes and neuroses or by a ‘lack’ that structure our everyday lives and which remain mysterious to us through the structures of our self-repression.[5]

The legacy of Duchamp’s Fountain, the many different ways the act, work or artist has been ‘imitated’, or the way he refers back to his own work, are aspects which are often characterized as a regress or return.[6] This is because, although the Fountain was destroyed, it was replicated as an ‘edition’ and also miniaturized hundreds of times in his various Boîte-en-valises,1935-41, a suitcase in an edition of 300, in which he crafted ‘replicas’ of his ‘originals’. Of course, each hand crafted or hand tinted object is slightly different in these valises, going somewhat against the grain of the story that Duchamp had an antipathy for artistic skill, traditionally defined. But the self-sustaining ideology that Duchamp parodied mechanical and commercial reproduction and the notion of the ‘original’ is itself a kind of pat and cyclical art historical interpretation, but one which contradicts itself, because Duchamp’s Fountain is cast in the role of the original when compared to many subsequent or even tacky imitations, such as the following mass produced, commercial ‘T ‘shirt.

An image of merchandise reproducing an image of Duchamp’s Fountain, www.acollective.com/tshirtblog/tag/art/</p>

On this view, the image of the ‘T’ shirt with Duchamp’s Fountain on it is a ‘repeat’ of the high art versus low popular culture binary, but is here convoluted into a ‘double negative’: a mass produced object reproducing a mass produced object, yet also transfigured into a urinal one can fit into. The shirt plays on the ambiguity of the urinal’s status as a mass produced piece of art, the ‘T’ vaguely echoing the shape of the urinal itself, according to formalist analysis. The ‘T’ shirt is a ‘low cultural’ mechanical reproduction of a ‘low cultural’ object (a urinal, a piece of plumbing). It also plays on a parody of taste and fashion (“why would you wear a toilet?”—‘because it’s art, silly”), and so puts art squarely in the eye of the beholder, for those ‘in the know’. For those even more in the know, the ‘T’ shirt transposes the Steiglitz photograph of the ‘original’ urinal and creates even further convolutions on the theme of mechanical reproduction. The high-minded might be reluctant to see that the ‘T’ shirt points to the heart of a problem, it is not found in an art gallery or institution, while Duchamp’s mass produced urinal is, and yet they are both mass produced, mundane objects, one referencing the status of the other. The ‘T’ shirt manages to raise the same issues about the status of art as Duchamp’s Fountain. In this sense it is not too far removed from Duchamp’s waistcoat readymades and the tradition of using clothes as modern sculptural artifacts. Yet it also reminds us that however much we insist the Fountain is a urinal, still it disingenuously reinstates the power of the gallery. The concave urinal, a container of piss, is the visual opposite of the full belly on which it is placed. The shirt also, jokingly suggests an invitation to those who see it to urinate on it, or on the person wearing it. But whereas Duchamp’s Fountain questions art, the ‘T’ shirt question the notion of fashion and art equally, and raises questions about identity and the body/self image associated with the fashion discourse. Thus, in presenting us with some form of meta-cognition, a critical awareness of the semiotics of the commonplace, and of other discourses, it is possible to step out of the vertiginous loop which interprets the Fountain as the original work of art repeated in ever fading copies, repeats which not only are supposed to re-present the repetitive processes of mass re-production but keeps the interpretation repeating. In short, the ‘T’ shirt is not a repetition, it takes the critical awareness we can garner from the Fountain to the realm of fashion, and sits uncomfortably in the world of ordinary objects, destabilizing it, as the Fountain destabilizes the world of art.

Some, at least, popular interpretations of Duchamp’s Fountain focus not on it as a parody of mechanical reproduction ad infinitum, but on its formal and perceptible qualities which bring into play not only religious, mythological and cyclical narratives of return but Freudian ones, too. The essentializing image of thought used for these purposes is the formal and aesthetic evaluation of Duchamp’s Fountain as a meaningful or suggestive shape (perhaps intended by the artist and chosen for that purpose, even though he was known to reject such ‘retinal’ explanations). Thus, through the inanimate porcelain form of the urinal commentators often glibly descry in the Fountain a ‘significant form’ a woman with a veil, a Virgin and Child, a Pietá, and even a sitting Buddha.[7]

http://www.yardwear.net/blog/2006/12/06/Nuns+Urinal.aspx

In the picture above of a functional urinal (the image has been published many times over on the Internet) the suggestive form of Duchamp’s urinal has been ‘outed’ and taken to its logical, if somewhat obvious conclusion. The implicit link here is between the sacred and the profane, and the ritual act of returning to urinate turns piss into holy water and the urinal into an altar, or mother of god, the cupola of chastity, the mother of material form. Urinating debases (materializes) these ideals either as an act of contempt, a Freudian slip, the male classificatory system of slut/virgin, or the logic of the joke, which is premised on the victim, blasphemy, a slight oddity, or an amusement by which the pee-shy can relax their sphincters. As a nun whose womb has been made into a container for the male’s fluid, it mimics sex but also borders on misogyny and contempt. This via negativa uses mechanisms of recurrence, habit, natural functions, oedipal structures and an appeal to childhood where mother potty trains her son, in order to reinscribe cyclical time. The natural or biological return of the urge to pee in this image of thought is a cyclical return which is also a mythical, religious, psychological and ‘artistic’ return.

We are caught up with circular models of time and mythical, religious or art historical circular narratives which lie alongside each other in an analogical relation—it is a system of analogies. Also circular here and related by analogy to mythical and religious themes is the Freudian association of urinating as a purifying activity, which not only gets rid of waste but flushes dirt away, as a hose pipe valorizing the moral use of the penis as an instrument that gives new life. In a typical mythological-psychological cyclical model, Freud suggests that the cleansing of the micturating penis reasserts masculine power over anal eroticism associated with representations of dirt and excreta, and can thus be compared to Hercules’ fifth labor, the task of cleansing the Augean stables of cattle dung by diverting the rivers Alpheus and Peneus (note the similarity of this word to Peneus to penis, despite having a different etymological root).[8]

Can Andres Serrano’s Piss Christ of 1987 lead us out of this regress? Serrano’s photograph is of a cheap mass produced, miniature cross with a figure of Christ crucified on it in a container of yellow liquid we assume is urine, given the title of the work. Without the title, one could easily see a clichéd image of the crucifixion in heavenly sunlight. The cross, the liquid, both are suspended, the symbolic in the biological, the biological in the space of the symbolic. Water, or the warmth of piss, are both indicative of life and they are continuous with each other. Water and piss are a double image which flow into each other, or rather, piss is the signature of the water of life. The urge to urinate is a natural cyclical return for all of us, equated here with Christ’s cyclical return in history. The Christian’s claim that Christ is human and must suffer this ignominiously is here taken to extremes, although again, the crucifix is but a mass produced object, not Christ. And so, as with Duchamp’s Fountain, we ask again, but is it art?

Because Piss Christ suggests the presence of the abject, a tainting with waste, with a marginalization which is beneath us to mention, we forget that it is a very intimate part of us in which Serrano has managed to insert the notion of god. Serrano does not use the accoutrements of urine to signify a ‘base’ human need but urine itself, not its image, and this is often forgotten in the sanitizing blandishments of revisionist explanations. Serrano nevertheless memorializes and ‘captures’ it, freeze-frames the crucifix in urine with the photograph. One could surmise that this is a meta-cognitive undermining of the claims of photography itself, to be another kind of body which ‘holds’ the moment, yet the body of ‘Christ’ is held in urine which could be his, the artist’s or anyone’s. The eternal return can be seen through the filth of mankind’s detritus, a phoenix rising from the ashes beyond the prison of the body and crude, base matter. Such an interpretation not only protects against the sheer force of nihilism, it recharges the notion of the eternal return of an ideology or tradition of thought. And yet, the interpretation is itself circular, caught up in the never-ending sado-masochism of basseuse (leading down, vertically to hell) and the anagogic (leading up, vertically to heaven). This hierarchical axis of culture versus counter-culture reinstates each of side of the opposition, reaffirms each of them locked in an eternally recurring conflict over a territory which is never really won or lost.

In this transfiguration of the commonplace, so the Fountain, a circuit of running water, somehow visually made appropriate to the fluency of the urinal as a self-repeating loop, is made both eternally binary, a male and female, something female to receive and something male to fill. The material form of the urinal elevated into a fountain becomes a symbol of actual and mythical return, of sexual reproduction as reproduction, the return of water as a circulatory system of ingestion and effluence, of purification and debasement, of being-in-the-world, the return of piss, the return of taking the piss. Again and again, tragedy and comedy are triggered by the return of the hero or anti-hero.

Freudian Repeats

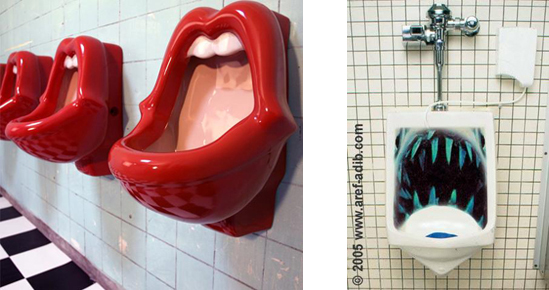

In the method of reducing objects to formal ideals in order to regain a lost time, or lost Platonic forms,[9] we would have to see the urinal as a vagina or a womb, a threshold which spawns a large number of reproductions in ‘high’ art, and a number of urinals in mass culture, drawing upon Duchamp’s toilet humor, a gendered humor that sometimes lapses into a crude misogynism. The following images show how the urinal in both shape and function slips easily into a (male) mass culture, excluding women, yet reintroducing their bodies as a target for ritual derision.

The Rolling Stones urinal (Left), http://www.bathroom-mania.com, Jaws – The Urinal (Right), www.aref-adib.com/archives/

Outside of the hallowed circle of art and religion, centered on the recurrence of the ideal through the muck of the present, is the ribald, urinal culture of male bonding. This is, at times, akin to the grotesqueries of medieval manuscript painting, where figures are contorted into bestial monstrosities, where ass kissing priests and somersaulting jugglers co-mingle with impudent nuns and monkeys morphing into composite creatures. Medieval margin art on the periphery of the sacred and the learned is an ambiguous space where bestiality and the carnivalesque are celebrated. In male toilets the same process of a topsy-turvy carnivalesque rewinds itself, centered on the morphing of the toilet into the imaginary, puerile ‘representations’ of Freudian drives and repressions. Here, it is not clear whether the urinal is a symptom of psychological syndromes, or whether their identification by Freudian analysis is parasitic upon them. This paradox is itself a circular, false ideology.

The public toilet is turned into a hetertopic margin space, a personal yet shared space, and the site for a code of silence producing the complicit unsaid of relieving ‘oneself’ (the male) of the exhausting affirmations of public image which erode belief. In this pathetic scenario, urinating becomes a confession to a nun or a whore. Here, the gaze, the stream of piss, and the coming clean cooperate. The gaze goes through the urinal’s aperture and cooperates with the phallus. One is reminded here of Michael Camille’s description of a monstrous figure of the gryllus in medieval illumination, an animal that had a head instead of genitalia, nothing more than an animal face lodged in the crotch of two legs, with no torso. He writes of the gryllus as “having a head between his legs instead of a prick. His look is an ejaculation.”[10] On another level, the gargoyle perched high on a gothic pinnacle of some Norman church takes on the shape of a phallus, and is used as a siphon to drain off water collecting in the gutters, surely a visual pun on male urination, where the gargoyle is the prick of the body of the church.

The easy flow of a natural function serves to naturalize the images of contorted mouths, anuses and heads as containers. The paradox is that urinating on or through these images or into containers figured in these ways makes them images, unreal, functional, made of porcelain, papier maché or paint, but one has to go through the jaws of association to achieve this materialization.

Even starker is the popular and ubiquitous ‘Rolling Stones’ urinal which references oral sex and the iconography of lipstick. Yet, undoubtedly, art history and psychology identify here the suggestion of the classic vagina dentata. This is made explicit by the Jaws urinal, which references the ocean and being swallowed up, as well as castration, which is denied by the act of peeing. Whereas, here the macho intent is to piss into the jaws of fear (a continual requirement for men who are repressed), the Rolling Stones urinal is meant to be a comic diversion. In the regressive image of thought which these images enhance, whenever men use a urinal, they reactivate a ritual, psychological act. Urinating is not only remembering but acting, remembering and shedding memory, or discharging discipline or energy. By appearing as a childish prank, the urinal as mouth is made speechless, allowing for an evacuation of analytical thought, an erasure effected by the incursion of an habitual and prosaic framing of events, the private joke, the surreal incomprehensible. The freedom to piss, left, right, up, down, a childish amusement, is continually contrasted with the anal retentive behavior of the restriction of movements, of disciplined cleaning procedures. Not to think so would be to lay oneself open to the worse charge of all, of lacking a sense of humor, camaraderie, irony, the inability to take these silly objects lightly, of harboring an aesthetic attitude violated by the urinal. And then again, we return to that yardstick by which all this is judged, the incomparable Duchamp.

What is remarkable here is the playing out, or one might say, materialization of psychological, metonymic modes of male phallocentrism and castration complexes, which occasionally stoops to misogynist or homophobic extremes, as we can see in the following two examples.

A urinal found in a Viennese Bar (Left), The Invitation to Urinate on an Aroused Male (Right), www. 13gb.com/pictures/2589/

In the first example, the woman as urinal is reminiscent of Allen Jones’s well known forniphilia or human furniture sculpture, where women are turned into coffee tables or chairs in contorted bondage positions. It is difficult to tell whether the urinal here, found in a bar in Vienna, is a play on Jones’s sculpture, or whether Jones’s sculpture merely exploits a common source of humor or irony.

A potentially anti-gay or homophobic version may be seen on the right which invites the male visitor to urinate into the belly of a contorted yet aroused male figure, with the idea that urination causes arousal in the passive recipient and contempt in the active user of the urinal. Of course, in a gay bar, this phenomenology would change, reminding us that context changes signs and deflects their meanings, as well as disturbs heterosexual universalizing phenomenology. In many of these cases, the male is invited to elide pissing with contempt, humor, or sexual aggression premised on edges and boundaries, lips, anus, vagina, edge of teeth, throat, and belly. It is curious that many men as a habit spit into the urinal first, before urinating.

Do these examples bring out the base, carnivalesque humor of Duchamp’s Fountain, or do they serve to vulgarize it, in itself a vulgar object, allowing us to see it with new eyes by showing its roots in male psychosexual toilet training rituals? But to answer in the affirmative would only succeed in vindicating the Freudian notion of repetitive, compulsive behavior. And yet the question remains, why is Duchamp’s Fountain, which inseminated a prosaic, functional object into art, considered art, while these examples are not? The fact that Duchamp’s Fountain was urinated on by several performance artists (Kendell Geers, Björn Kjelltoft, Yuan Chai and Jian Jun Xi), means that we cannot state that these ‘low-life’ examples are functional, whereas Duchamp’s Fountain is not. And there is also a logical conundrum here. Duchamp’s Fountain was meant to pierce the boundary or edges of art leaving it open to the lowly and the vulgar, yet this opening will not, however, allow passage for the series of ‘abominations’, the real urinals becoming animals, fish, buttocks, mouths in everyday life.

An interesting aside to this is a ‘political’ act of urinating where we have a urinal in the image of President G. W. Bush (another with a picture of Saddam Hussein on it, and yet another with a Qur’an pictured on it[11]) which clearly show that male urinating can routinely elide into an act of contempt or cynicism, or postmodernism, depending on the eye of the beholder. As with the mechanism of the joke, the laugh releases tension at the expense of the ritually humiliated.

Pissing Politics, gizmodo.com/gadgets/toilet/

The point here is that from a position of ‘high art’, art historical analysis adopts Freudian psychological ‘distance’ or postmodernist irony to exploit ‘low art’ and the toilet humor of public conveniences and their underlying syndromes in order to sustain such analysis. Both analyst and analysand mutually support each other in a perpetual cause and effect, although it is often not clear which plays the cause or the effect, as their roles are reversible. This circularity can only be broken by feminist and gay interventions using Deleuzian difference and repetition, as I argue in the last part of this essay. But there is one other, problematic model of time and consciousness which I have mentioned, that of phenomenology, which needs to be dealt with first.

Phenomenological Time

Much of the analysis so far reveals the circularity of both psychological and phenomenological interpretations of art which are sometimes insightful, but most often work on the logic of cyclical time and unavoidable drives and representations played out as a ‘natural’ order: where ‘men can’t avoid being boys’ a circularity which valorizes a helplessness/truthfulness conundrum. One begins with a classical phenomenological fallacy with Duchamp’s Fountain, does the urinal keep returning or do we keep returning to the urinal? Put in this way, it is a male question, something that phenomenology conveniently conceals when positing the “I”, or indeed, the “we”.

But we must be careful not to simply assume that the phenomenological first person is white, heterosexual, able-bodied and male, providing a foundation upon which knowledge should be based as a universal condition. Deleuze’s second critique of time is linked to Kant. This model of time extends not only to phenomenology but to the phenomenological interpretation of art and is seen as a straight line. In the Critique of Pure Reason, Kant cuts up circular time and reassembles it as a series of sensory experiences which memory processes and which constitute subjectivity.

Whereas the circular model of time (and interpretation) inscribes a fatalism into the subject and the world, the phenomenological method is in danger of solipsism, where the subject constitutes the world. Much of embodied philosophy and enactivist theories of cognition go down this line with a plethora of art historical analyses by the likes of Rosalind Krauss, Michael Fried and others taking the lead from Merleau-Ponty. These approaches successfully challenge the homunculus model of a Cartesian mind-body dualism where there is a supervisor in the mind who processes experience and even consciousness and to whom all representations are directed. But phenomenology is mainly concerned with perceptual consciousness, the processing of colors, shapes, forms, motion in art and the world. The senses and sensorimotor processes are the fundamental pathways by which the interior is connected to the exterior in a chiasm of self-constitution in the world.

The problem with this is that we explore the art through our sense perceptions, and what does art reveal to us?—our sense perceptions! Such solipsistic approaches have real problems relating complex and abstract conceptual production to bodily and sensorimotor contingencies, and they nearly always posit the subject as the site and object of discovery in the world. To be fair, phenomenology has moved on to rather more sophisticated models of intersubjectivity, taking into account the specificities of different kinds of bodies and ways of being beyond the white, male heterosexual as the common denominator, yet many naïve approaches to art perpetuate the notion that perceptual, rather than conceptual processes and evolutionary neural patterns are primary, fundamental ways to understand the art experience.[12] In fact, these aspects are only part of art production and reception, aspects which are often filtered out or made known to us in order for us to parody such trigger responses, as in much of Duchamp’s work, which holds in contempt such retinal approaches to art.

If we take the subject of abstract expressionism in the 1950s or later minimalist art, art history, teaching and interpretation still insists on putting the act of perceiving as fundamental to the constitution not only of the phenomenological first person but also of art itself. The male act of urinating, usually standing up, which consists of directing a stream with the hand(s) into a container or on a flat surface, sand or snow in order to leave patterns and traces (the usual child’s prank) underlies the logic of macho 1950s Abstract Expressionist culture, especially that of Jackson Pollock, so effectively parodied by Carolee Schneeman’s Vagina Scroll, 1975. Here, painting or writing is a kind of pissing, a discharge which invests the object and space with the phenomenological “I”, disciplined by existential struggle and reflected back by the traces, signatures and gestures left behind in the work of art, rediscoverable as an element in the making of other subjectivities.

It is precisely this kind of solipsism which is blind to the art event as something well in excess of re-establishing habits of subjective self-identity through the production and interpretation of art. The attempt to reinforce a phenomenological identity upon the event by personalizing sense experience is unable to see art as something which remodels the phenomenological ‘I’ and neural plasticity itself. We learn new technologies and redraw our neural pathways through such new and spontaneous experiences which draw us into intersubjective worlds.

Gay and Feminist accounts in art history have inserted difference into the phenomenological equation. Warhol’s Oxidation Paintings in 1978 are often referred to as his Piss Paintings. On one occasion he chose a gay friend, Hugo to urinate on his canvas coated with copper which would then oxidize into different colors:

[…] because Hugo had an unusually large bladder, not to mention an unusually large penis, which was why, Andy slyly speculated to friends, Hugo was the lover of his friend Halston. When Hugo peed on a canvas, his urine reacted with a chemical compound that had been painted on the canvas, creating a mass of lines and squiggles.[13]

This quickly became a conveyor belt system of producing paintings where several men were invited over a period of time to drink wine and relieve themselves on Warhol’s murals. Apart from recreating in microscosmic form, gay watersports culture in his studio, like Schneeman, Warhol managed to parody the exclusive macho heterosexist culture of abstract gestural art. Warhol admitted ‘taking the piss’ out of Pollock and his action painting techniques of dripping and splashing and his bouts of drinking and urinating for which he was infamous.[14] Yet Warhol also managed in true conceptual art fashion, to remove himself from the act of painting, as had Duchamp with his urinal, instead, busying himself with the pleasures of looking, directing and conceptualizing. The subversive element in all this was fun mixed with art, meaningfulness hitched to meaninglessness:

[…] there were many others: boys who’d come to lunch and drink too much wine, and find it funny or even flattering to be asked to help Andy ‘paint’. Andy always had a little extra bounce in his walk as he led them to his studio […] Victor [Hugo] was showing up with ever larger numbers of ‘assistants’, hired by the hour at the Everard and St. Marks Baths.[15]

Warhol thus created a difference which consisted in subverting the existentialist angst of macho drinking and pissing culture and notions of serious art, autonomous writing, performance art in order to deterritorialize painting, pissing and the legacy of Duchamp and Pollock with a particularly gay, if somewhat specialist, inscription. The Piss Paintings are a particularly social, productive, intersubjective becoming of collective desires which celebrates a seriality, an outline of practice, or a playful laughter against solipsistic grandeur, contempt for difference, or indebtedness to the past.

Warhol’s Piss Paintings also poke fun at the standard psychological definition of such activities when associated with sexual arousal. These stories from Warhol’s biography are ambivalent in this regard. For Freud and others, the Piss Paintings might be understood as a resurgence of compulsive, sociopathic personality disturbances. In classic scientific classifications, these kinds of urination practices are the result of sexual deviation, repressed childhood abuse, or some other pathological disorder, or even the result of a neurological disease, a far cry from an art historical interpretation which recognizes here, degrees of volition and the social, intellectual, political and artistic origins of such actions in the production of art.

Difference in Repetition

Although some artworks are more easily inserted into the circular time model or phenomenological narratives than others, Deleuze’s concept of difference and repetition allows us to see history more productively. Artworks which, on the surface of it, seem to duplicate or reference others are, in fact, in their own ways an ‘event’, yet ones which nevertheless signify in a series, one that does not need to go back to an original or archetype. This is a series of discrete differences which, nevertheless, can refer to other works in an open ended intertextuality. It is this quality of signifying both the recurrence (or ‘repetition’) of difference, and difference from itself which brings to mind Deleuze’s complex meditation on the eternal return.

With each event of difference, life and art are affirmed as they are changed. If it is only difference which returns it returns eternally, and this is Deleuze’s take on the eternal return: only one thing is constant, and this is change. But this change is understood in a rather more complex, ‘transgenic’ way than the evolutionary model allows. The principle of becoming means that each event may be a marshalling together of many elements in the same duration. Elements or works of art in various kinds of series recombine with other series exploring and making a multiplicity of serialities. These are not reducible to a master copy. In terms of interpretation, it is the insertion of feminist and gay sensibilities into the Duchampian seriality of the Fountain which adds important differences to the Fountain and distributes it, as it is distributed onto a number of different planes.

In this concluding section I intend to create a rather unconnected number of juxtapositions of art works that reference Duchamp’s Fountain as a way of avoiding an essentialist narrative or art history based on sequential procession. Rather, each artwork, its production and reception, are an event which goes through a process of becoming in a larger multiplicity of artwork-events. Instead, the artworks dealt with here and the mode of presenting them should be seen as a series of differences which evade the circular or phenomenological expositions of time and meaning, both of which depend on a telos of progressive revelation centered on the viewer as experiencer. Instead, the artists whose works reference Duchamp’s Fountain are not to be seen as repeats, but make immanent a radical heterogeneity.

The following is only a brief listing of the various ‘simulacra’ of Duchamp’s Fountain: Robert Gober’s slanted or double sinks and double urinals appear as altarpieces or Freudian doppelgangers, referencing same sex interaction. This is taken to monstrous extremes by Thomas Koh’s 21 foot long white urinal in 2008-9 which appears to fuse the urinal series into unitary concept which swamps individual use. Bruce Nauman’s, Self-Portrait as a Fountain, 1966-70 casts the body in the role of a urinal or a fountain; Claes Oldenberg’s flaccid and incontinent Toilet, 1966. Other works are Elaine Sturtevant, Duchamp Fountain, 1973; Hans Haake, Baudrichard’s Ecstasy, 1988; Sylvie Blocher, Le Parloir, 1990 (an installation piece of five urinals); Sherry Levine’s Fountain 5 (After Duchamp), 1991; Mike Bidlo, The Fountain Drawings, 1993-1997; Lea Lublin’s le corps amer (à mère), l’objet perdu de M. Duchamp, 1995; Sarah Lucas’s, The Old in Out, 1998, using the urinal form again in 2002, with twenty urinals hung onto a wall in an exhibition space; Tom Sachs, Chanel Fountain, 1998 (a black version of the urinal with a reference to perfume, an ironic and rare appeal to the olfactory sensibility of the urinal); Nelson Leirner, Sotheby’s, 2000, a tube connecting two urinals side by side; Jimmie Durham, He said I was juxtaposing, but I thought he said just opposing. So to prove him wrong I agreed with him. Over the next few years we drifted apart, 2005—a broken urinal with fallen head on an exhibition wall with a plaster cast head of a statue beneath it; Richard Jackson, Pump Pee Doo, 2005 (bear with urinal head) and Kendell Geers, Homage to Alfred Jarry, 2006 (a black and white urinal with chains, links and helix designs on it). There are also Clark Sorensen’s exotic, kitsch urinals in the shape of conch shells and orchids.

A ‘different’ channeling of the fountain of Duchampian seriality was Helen Chadwick’s Piss Flowers completed in 1991–92. Chadwick created twelve bronzes coated with white enamel, cast from patterns made by urinating in the snow with her husband David Notarius. There is a knowing gesture here to Robert Smithson’s Urination Map of the Constellation Hydra of 1969 where the artist urinated in several puddles in the ground marking each star point in the constellation (while quoting Alexander Pope’s poem about a pissing contest between poets), possibly a reference also to Pollock. Here, effectively, Smithson marks the earth with the fire of the stars, with water, and through the air, linking his body to the land. With Chadwick’s ‘land intervention’, pissing is transformed from an unremarkable biological fact into a co-creation of art between male and female, ostensibly dissolving an unsaid symbol of patriarchy which resides in the man’s supposed privilege in the phallogocentric economy, using the phallus as a pen to reinscribe his trace, the law, whether in painting, on sand, in the snow or into the earth. Here, Chadwick showed that this need not necessarily be so, highlighting the social taboos by which women’s bodies are regulated, and challenging stereotypes concerning female urination and control. At another level, the artist demonstrated that the (male) negation (of anus, vagina, society), through which male bonding is instantiated in order to reaffirm the phallus as active tool in a self-referencing cycle can be rechanneled into art. Pissing here becomes the basis for a precise and exacting process of intensity, namely, the bronze casting and enameling techniques by which a quiet determination and investment of time, energy and sensation succeed in creating difference in repetition, and a something from a nothing.

The urinal is not only in the eternal service of the redneck’s butt of the joke, it is also, paradoxically, used by artists to savage conservative standards of aesthetics and decorum. This paradox is certainly evident in Sarah Lucas’s The Old in Out, 1998, which introduces an ingenious autonymy, whereby urine-yellow transparent plastic is molded into the shape of a toilet, and reproduced several times. Although seemingly made of liquid in the containing shape of the toilet, it continues irrationally to hold, reversing sensible notions of inside/out, container/contained (indexing the title The Old in Out which could also be, the old in/out dualism). Also juxtaposed here is a kind of binocular rivalry between organic/inanimate, solid/liquid, art/waste, personal/impersonal, form/matter, and absence/presence. The lavatory here is magically made invisible and yet is still ‘there’ and when we conceive of the shape of the lavatory, the urine tends to disappear. We needn’t decide on either side of the binaries set up here, just revel in their incomprehensible unity.

In Lea Lublin’s le corps amer (à mère), l’objet perdu de M.Duchamp, 1995 the artist produces a maquette of a pregnant woman’s torso on which is placed an image of Duchamp’s Fountain which literally makes explicit the formalist interpretations of Duchamp’s work as something suggesting a uterus. The implicit here is made explicit by spatially extruding the convex, pregnant belly which paradoxically shows the urinal as a concave shape. The pregnant meaning is outed, and Duchamp’s urinal made to procreate with the aid of the artist.

This emphasis on a woman’s creative powers was explored by Mike Bidlo’s 1995 work modeled on the Fountain entitled, Origins of the World, referencing Courbet’s painting of genitalia, which in turn, was referenced by Duchamp’s Fig Leaf sculpture, 1950, Duchamp’s own ‘reversal’ of the Fountain as a male signifier. Bidlo placed Stieglitz’s famous photo of the Fountain before a painting by Marsden Hartley and behind this a copy of a pink rose flower painting by Georgia O’Keefe peeping through, suggesting, as many of her paintings do, a vagina. This complex chain of signifiers continually places the vagina as the active ‘origin’ of the work of art as opposed to a passive receiver of the male principle, transforming the male urinal as origin into a procreative female vagina, and creating an alternative lineage. Clark Sorenson’s urinals in the shape of shells and orchids make the link between Georgia O’Keefe flowers, vaginal folds, urinals and Duchamp rather more obvious. But Bidlo succeeded in creating a rhizome of sorts, suggesting transversal connections, an “and, and, and”, a weed which destabilizes rational, psychoanalytical and teleological narratives by producing unexpected juxtapositions.

He said I was juxtaposing, but I thought he said just opposing. So to prove him wrong I agreed with him. Over the next few years we drifted apart, 2005, is the title of a work by Jimme Durham that consists of a broken urinal on the wall with a fallen plaster head on the floor before it. This references decapitation and castration, as well as the body/mind duality, yet manages to suggest in a visually innovative manner that juxtapositions or oppositions of this kind allow the viewer to imaginatively create a third term, a body or a body as urinal, the ‘body’ of art, or a drift from or towards the title of the work. The missing torso (perhaps it isn’t missing, maybe the torso is the urinal) is not only a whodunit, but a missing lexical unit. As Duchamp quipped, “What art is in reality is this missing link, not the links which exist. It’s not what you see that is art, art is the gap.”[16]

Nelson Leirner, Sotheby’s, 2000, consists of two replicas of Duchamp’s Fountain, one of which has a tap fixed on it joined to the other by a tube of water, connecting them like an umbilical cord or hospital drip, and yet they are merely inanimate objects. Art reflects back our faciality, the need to anthropomorphize in order to understand. The work brings to mind notions of circulation, reproduction and autogenesis, of water and of biological homeostasis, echoing Hans Haake’s work, Baudrichard’s Ecstasy, 1988. In both cases, a biological cycle of return parodies the return of Duchamp’s Fountain. Haake explains his piece in this manner:

In the second half of the 80s, like in Europe, New York was inundated with the sayings of Chairman Baudrillard. This piece is my comment. I called it ‘Baudrichard’s Ecstasy.’ As you see, there is an ironing board supporting a urinal, both obvious references to Duchamp. The urinal is gilded. Duchamp’s, of course, wasn’t. And there is a fire bucket suspended from one side of the ironing board. Water from the bucket is shooting through a hose, out from the top of the urinal, and into the hole on its bottom. Then is flows back to the bucket. In the title I’ve contracted the names ‘Baudrillard’ and ‘Richard.’ ‘Richard’ refers to the ‘R’ in Duchamp’s pseudonym ‘R. Mutt.’ In French ‘Richard’ also means ‘moneybags.’ The ‘ecstasy’ of the title is a reference to an essay by Baudrillard, ‘The Ecstasy of Communication.’ As you see here, Baudrillard’s orgasm, so to speak, amounts to nothing. It is infertile.[17]

For Baudrillard, the “ecstasy of communication” means that the subject is bombarded by instantly produced images and information. The subject “becomes a pure screen, a pure absorption and re-absorption surface of the influent networks.”[18] Haake’s conceptual art work illustrates Baudrillard’s circular pessimism but ruptures it by showing that not all image production (Haake’s in particular) needs to be a passive and inevitable processing of simulacra, a grim and escapable absorption or re-absorption, the stifling of the new by a circularity of cause and effect. The work references Duchamp, but not in a repetitive or slavish manner, and demonstrates the ability to create new works in an open ended intertexuality, while at the same time, physically, materially and conceptually creating an event which speaks and in itself demonstrates a joyous conjoining of materials and ideas. The work is a visual and material critique of powerlessness and regress in both critical theory and art. It is pure production as production referencing itself, a heterogenesis of elements, readymades, words, references to Duchamp’s Fountain and more.

Far from being an immutable Platonic form continually indexed by replicas, each artwork negotiates the concept of the original and the ‘original’ concept with its own difference. Conceptual art of this kind even begins to question the Deleuzian logic of sensation which sets art apart from philosophy. With this work and many others I have mentioned here, it is possible to see this bifurcation between the concept and sensation as a fold, separate but joined together as an event which would be inadequate to describe using the customary dualisms.

Addendum

The ability to return is realized by forms of diversity and multiplicity in their continual heterogenesis, and focusing on the legacy of Duchamp’s Fountain in the anti-aesthetic sense, as I have done here, helps us to gauge this in a positive way. For not only is difference reaffirmed but it challenges reactive ideologies and interpretations of art, life and the world. The ideology of recurrent time is everywhere in our literature, science fiction, popular culture and art, yet its enslavement of desire is rarely questioned because we are so enamored of time travel and the recurrence of the self in posthumanism as a form of immortality.

I have tried to show that art interpretation is also a way of reasserting models of time and destiny by which we seek to structure reality. Deleuze’s difference and repetition, however, is an affirmation of the present continuous without resorting to paradigms of self-same repeat, repression, or solipsism. The lowly and contemptible urinal has been taken up by many artists for many different reasons, yet this multiplicity succeeds in breaking up phallogocentric regimes of (fictional) recurrence based on the cult of the artist, the phenomenological “I”, or the haunting of Freudian psychopathologizing which block any sense of joy, volition or creativity. Duchamp’s Fountain should not be understood simply as an eternal return, but an eternal return of a continuing transvalution.

[1] For an analysis of the relationship between repetition and Gerard Richter’s work, see Simon O’Sullivan, Art Encounters Deleuze, Thought Beyond Representation, Basingstoke, Palgrave, 2008, p. 134; for Leonardo, see Adrian Parr, Exploring the Work of Leonardo da Vinci in the Context of Contemporary Art and PhilosophyLewiston, N.Y. : Edwin Mellen Press); and Dorothea Olkowski, Gilles Deleuze and the Ruin of Representation Berkeley, CA; London: University of California Press, 1999, where the author analyses the work of Mary Kelly.

[2] Deleuze, Difference and Repetition, p. 55.

[3] Keith Ansell-Pearson, Germinal Life : The Difference and Repetition of Deleuze, London, Routledge, 1999, p 92.

[4] Mircea Eliade, The Myth of the Eternal Return: Cosmos and History (trans. Willard R. Trask), Princeton University Press, Princeton, 1971.

[5] Although challenged by a number of feminist writers, this system of regress can be seen clearly in the way Freud treats the Oedipal complex, Sigmund Freud “Female Sexuality” (1931) in The Standard Edition of Sigmund Freud, London, Hogarth, 1961.

[6] See for example, David Joselit, Infinite Regress: Marcel Duchamp 1910-1941, Camb. MA, MIT Press, 1997.

[7] Claims once again renewed by art history in the form of Majorie Perloff, ‘Dada Without Duchamp/Duchamp Without Dada: Avant-Garde Tradition and the Individual Talent’ Stanford Humanities Review, 7:1, 1999 at http://www.stanford.edu/group/SHR/7-1/html/perloff.html Accessed, January, 17, 2010. Thierry de Duve maintains that the many artists who have used Duchamp’s Fountain as a reference are suffering from a religious or paternal nostalgia or trauma. Thierry de Duve, ‘Mary Warhol/Joseph Duchamp’ in James Elkins and David Morgan, eds. Re-enchantment, New York: Routledge, 2009, 87-106. This is the typical kind of negative, reductionist explanation of art or history which Deleuze’s difference and repetition aims to dissolve. Such an approach is itself circular, reinscribing Freudian schemas and religious patriarchalism into interpretation.

[8]This particular Freudian analysis is taken from Lee Edelman, ‘Piss elegant: Freud, Hitchcock, and the micturating penis’ Gay and Lesbian Quarterly, Vol. 2, pp. 149-177. Edelman sees anal repressions almost everywhere in Hitchcock’s Psycho, so that his essay ‘anal’ ying this film, reads almost as compulsive repression spotting behavior. The essay demonstrates in its writing the mechanical and circular method of Freudianizing of Freud and the fatalistic pessimism of the psychoanalytical method of negations, repressions, and neuroses, pp. 151-2.

[9] See this tendency in art interpretation in Adrian Piper, ‘Ian Burn’s Conceptualism’, Art in America, December, 1997, 74. Similarly, because for Danto art is embodied meaning, meaning is prior to its embodiment yet dependent on it. Yet the correct emphasis for meaning creation should also be shared with the viewer, meaning is also produced in cooperation with the viewer not merely extracted as a preformed idea from its embodiment. Instead, it is negotiated not repeated by embodiment.

[10] Michael Camille, Image on the Edge. The Margins of Medieval Art, London, Reaktion, 1992, 41.

[11] Published mypetjawa.mu.nu/archives/2005_05.php Accessed January 12, 2010.

[12] See for example, Mark Johnson, The Meaning of the Body: Aesthetics of Human Understanding (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 2007); Alva Nöe, ‘Précis of action in perception’ in Psyche 12:1, 2006 and many other neurological or enactive approaches to art which cannot account, as yet, for possibly the most important aspect of art: conceptual production.

[13] Paul Alexander, Death and Disaster. The Rise of the Warhol Empire and the Race for Andy’s Millions, Paris, Vilard, 1994, 46. Quoted in an informative and amusing text, published online, ‘Andy Warhol’s Piss Paintings’ http://www.warholstars.org/aw76p.html Accessed, January 12, 2010.

[14] “I’m pretty sure that the Piss Paintings idea came from friends telling him about what went on at the Toilet, reinforced perhaps by the punks peeing at his Paris opening. He was also aware of the scene in the 1968 Pasolini movie, Teorema, where an aspiring artist pisses on is paintings. ‘It’s a parody of Jackson Pollock,’ he told me, referring to rumors that Pollock would urinate on a canvas before delivering it to a dealer or client he didn’t like. Andy liked his work to have art-historical references, though if you brought it up, he would pretend he didn’t know what you were talking about” Bob Colacello, Holy Terror: Andy Warhol Close Up NY, Harper Collins, 1990, p. 342. Quoted in http://www.warholstars.org/aw76p.html Accessed, January 12, 2010. For an excellent essay on Duchamp, Charles Demuth, Warhol and others, see Johnathan Weinberg, ‘Urination and its discontents’ Journal of Homosexuality, Volume 27, Issue 1&2, September 1994, pp. 225-244. Weinberg also sees Warhol’s oxidation paintings as an act of transgression against abstract expressionism and treats the subject of urination, particularly gay examples, as something that has been ignored in art history. Yet he also writes that Pollock’s drip paintings and Warhol’s oxidation paintings were “a kind of return to pre-civilization—they are truly primal” (p. 232, my italics).

[15] Colacello, 1990: 343.

[16] Quoted in Dalia Judovitz, Unpacking Duchamp: Art in Transit Berkeley, University of California Press, 1995, p. 135.

[17] Interview with Hans Haake: http://www.undo.net/cgi-bin/openframe.pl?x=/Facts/Eng/fhaacke.htm Accessed, 12.01. 2010.

[18] Jean Baudrillard, The Ecstacy of Communication, Cambridge MA, MIT Press,1988, p. 27

Gregory Minissale is Lecturer in Contemporary Art and Theory at the University of Auckland and is author of Framing Consciousness in Art: Transcultural Perspectives (Amsterdam and New York, Rodopi, 2009).