Jonathan VanDyke

All images by and courtesy the artist.

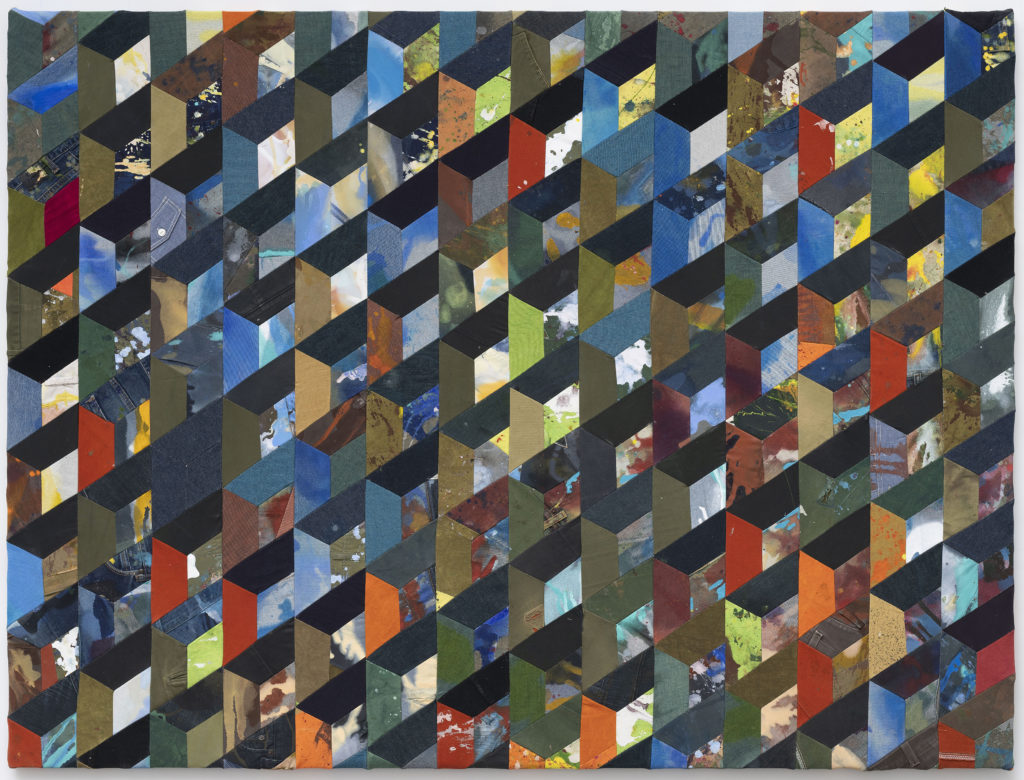

The Greens, 2019. Ink and water-based paints and dye on cotton fabrics, backed with dyed linen, with photos printed on archival canvas on verso. 68.8″ x 94.5″.

I’m thinking through your term queerfacture. Queerness is a way I’m embodied, a suffusion of my person reflected in the ways I make and do. It includes a lot of feelings that I can barely even touch and tendencies for which I can’t find words. To live as queer is also to internalize all the acts of resistance and harm you’ve experienced, while gauging those you might yet face. Imagining and making and gathering differently – queerfacture – is a way of working through, letting go, transforming.

I notice in myself a perpetual assessment of my self-presentation, an extreme unwillingness to be fixed. It’s why I love commas. It’s probably why I’m always on the move. And it shows up in the way I make my paintings in pieces, ripping things apart, putting them back together, setting them up so that you observe them from every side.

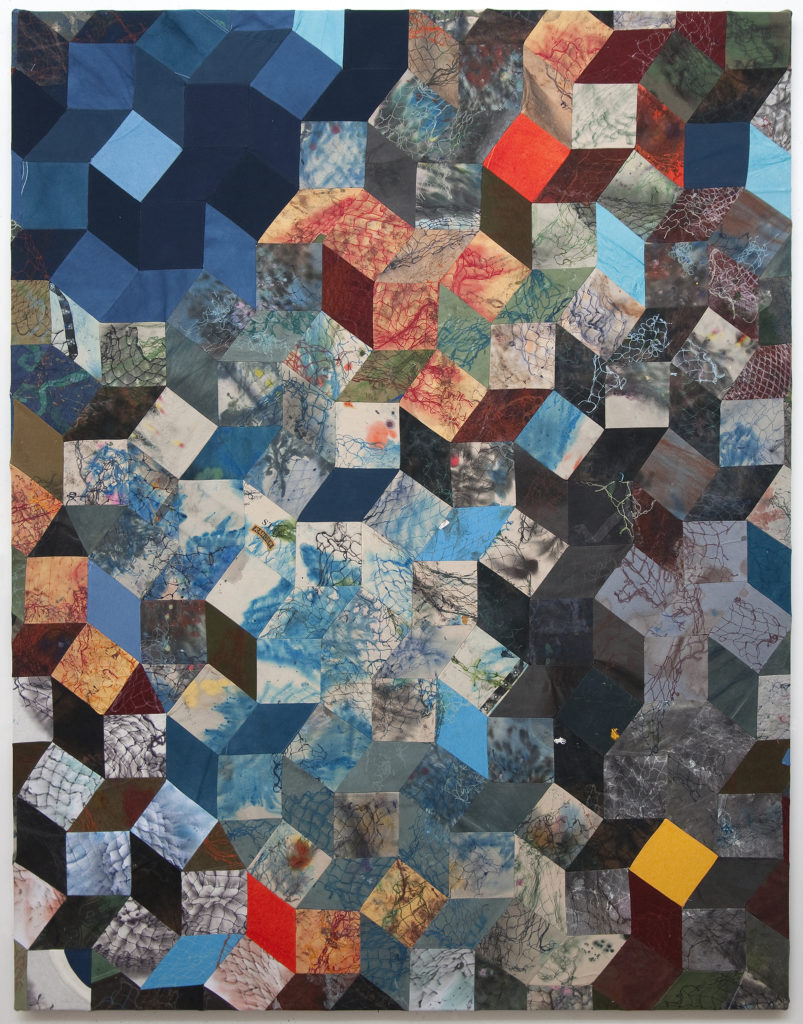

In a Different Voice, 2019. Water-based paint and inks on cotton t-shirt material, cut and sewn; backed with dyed linen and photos (archival prints on canvas). 82 3/8″ x 63 7/8″ x 1 5/8″.

*

We assume that living openly queerly has become easier, especially for young people. This oversimplification diminishes the difficulties faced globally by many, if not most, who want to love and express their gender outside of convention. For me, coming out was a matter of palpable risk and sizable loss, and for years I performed as straight. While passing you learn to study and assess what you’re up against. Living queerly is a long slow process of losing the grasp of forces that are controlling you, of walking off the lines you’re not able to follow. You encounter the tracks of others who have wandered off those lines. Queerness, of course, might be just one of many reasons a person has been pushed aside. Our veering “slantwise” (in the words of scholar Sara Ahmed) might engender solidarity with others who diverge, slant, wiggle, fall, and lose course.[1]

Isn’t being an artist also a matter of finding the courage to call yourself an artist at all? It’s a type of coming out, of rehearsing into a role. (How many dances did I perform alone, in my bedroom, before I brought them to the party?) We can’t make our work without making ourselves. But who makes us?

Expecting, 2017/21. Pigment print. 15″ x 10″. Edition of 1 + 1 AP.

My childhood experiences prepared me to perform differently. I grew up in the Pennsylvania countryside amidst my father’s cohort of wonderfully weird artists and radically progressive public-school educators. They showed me how to gather sheep wool to make felt, plants to make paper, and garbage bags to make inflatable sculptures. I became media-fluid, translating my abstract watercolors into latch hook rugs, and drawing on my jeans with bleach and ball point pens. My “Uncle” Gary, most beloved of my father’s friends, presented an alter ego named Gloria who dressed up in my Mom’s clothes and posed for her camera.

An Atmosphere, 2019. Ink and water-based paints and dye on cotton fabrics, backed with embroidered and dyed linen, with photos printed on archival canvas on verso. 69.5″ x 50.5″.

I was a gay child raised in the encroaching shadow of the AIDS crisis, and I became preoccupied with fear as several of these queer uncles disappeared, and as I was bullied for my bleached jeans. (And despite my parents’ inclusion of queers in their circle, they didn’t easily accept a gay son.) When the conservative talk show hosts and fundamentalist zealots railed about a plague that was made for us, they were paying no compliment. As I gravitated to art classes, I heard a teacher saying that painting was dead, and so I headed towards it – an apt ghost for my proclivities.

Living openly queerly runs the risk of being dismissed and disliked. Certain strains of punk and rap and alternative and goth music – along with the beautifully angry chords of noise I heard my brother playing through the wall that separated our childhood bedrooms – once helped point the way. And the point was to not be liked.

*

It seems quaint that my high school friends and I called each other “conformist” as an insult. Now me and my fellow adult queers and art punks live in and through a culture of likes, with social media templates locking up ways of seeing and being seen. Shouldn’t queers be generating other methods for sharing?

I began my career working in museums, and I often heard visitors say, “That’s different,” and “I just know what I like,” to brush off difficult objects. Even as someone who champions difference and difficulty, I too count likes online and hope for followers, scoring gains, sinking into questions about my work’s value – which for an artist inevitably short circuits into valuation of the self. I’ve watched art students react with near despair when they post their work and it doesn’t get many likes, looking at me incredulously when I encourage them not to conflate the quantity of hearts with the authenticity of their imagination.

How to Operate in a Dark Room, 2019. Installation view, solo exhibition. 1/9unosunove, Rome.

We’re just beginning to reckon how social media companies have consciously manipulated us for maximum reaction. Our fear of dislike is not a side effect of these platforms; it’s what they depend upon to keep us hooked. Algorithms feed us certain images at the expense of others. Living openly queerly is a demand for visibility. But we can’t view or trace the digital calculations that push some images off the line.

The art world and the art market also depend on opacity, with curatorial decisions shrouded in theory and pricing shrouded in fame. What appears as a system of belief occludes a system of profit. It’s no coincidence that figurative painting began to rise (again) in the global art marketplace just as Instagram became the prime circulator of art world images. Not only are representations of bodies easier to notice if you’re scrolling quickly, but the algorithm sends you images of bodies more quickly than images of anything else. Flat, quickly legible works of art are more digestible, scroll-able, shoppable, post-able, than multi-sided or time-based or just plain complicated forms, which don’t fit so well in fast-moving rectangles.

Non Violent Protest, 2013. 20 x 13.5 images. Pigment print. Edition of 1 + 1 AP.

*

I won’t begrudge any artist for gaining profits, but commodification can be so swift and so totalizing – in cities that are so totally expensive – that I wonder and worry about the survival of the studio as a place of weirdness, of queered-up processes without ends and experimentation without monetary means. In MFA critiques people often ask, can’t you fuck this up? I used to teach in the graduate art business programs at Sotheby’s and at Christie’s, where that question was never asked. I designed a class focused on how to work with artists and prioritize their needs, but my efforts often fell flat. I felt like an interloper, a marketplace spy. Once I attended a lecture by an auction house head, and she spoke plainly about “art today” as the ideal “portable asset,” perfect for your “second home, your plane, your yacht” – as if there were no messy, feeling body behind its making.

The auction catalog, with its numbered lots and its dollar estimates listed near the top line, constrains the work of art, most especially painting, as a fetish object for those who need to externalize their wealth; the same happens in the clinical atmosphere of the white cube gallery. The farther the market separates itself from our messy studios, the more easily it can just recall artists as fabulous, crazy, stylish, difficult, cute, queer. The market uses these descriptions to enforce systems that occasionally support, but almost never sustain, the practice or the total person.

Making good art is mysterious and crazy-making, but it’s also a ton of work. In the US we create aside a government that has systemically eliminated support for artists. In 1989 on the Senate floor, arguing against federally funded, individual artist grants, Jesse Helms described Robert Mapplethorpe’s work as “trash.”[2] I internalized this idea, too, and at best, it gave me the courage to see my job as counter-cultural, rude, radical. Queer trash.

Verso view of In a Different Voice, 2019. Installation at Des Moines Art Center for Queer Abstraction. (Sol LeWitt wall mural in background). Images printed on back of painting: Iraq war falling soldier image by David Leeson for The Dallas News/AP, 2004; portrait photo of CPL Andrew C. Wilfahrt, 1979-2011, first openly gay American soldier to die in combat].

I work across media, investigating where disciplinary lines intersect, and I think a lot about the fixed binaries that markets and institutions hand us: painting versus sculpture, painting versus photography, flat versus dimensional, art versus craft, art object versus art maker. Just as we queer folks are unravelling the binaries attached to gender and sexuality, can’t we unravel these art world binaries, too? The porousness between the artist and their work needles the whole system. I think we should needle it more. And yet, the most trenchant binary – that between the very rich and everyone else – is less a fabrication than any other, the hardest one to dent.

Amend, 2018. Acrylic, ink, and oil paints on denim and twill fabrics, with overdyed denim and twill; cut and sewn. 71.5″ x 74.75″.

*

In 1951 Cecil Beaton photographed models in French fashions, standing in front of large-scale Jackson Pollock paintings, accompanied by the title “The New Soft Look,” all of which apparently freaked out Pollock, who wouldn’t dare be associated with feminine fashion or with soft. I think of this when I invite friends into the studio and ask them to dress up in front of my works-in-progress, and I take pictures which are sort of like paintings, one moment in a long process without boundary or end, all of us performing together.

I’ve been making almost-paintings from beautifully soft materials, gathered from friends and lovers, used t-shirts and jeans and twill pants, carrying bodily memory and sweat stains, the fabric between the thighs worn through. Over months these materials are worked – stained, prodded, coated, dyed, marked, cut to pieces, and then slowly pieced and sewn back together in an act of patience and of repair. I hope these works have an illusory beauty – they’re not paintings in any conventional sense – something like a drag queen performing as Marlene Dietrich, who herself performed as someone else. Scholar Heather Love talks about the queer insistence on “feeling backward,” fixating on the past, reinserting ourselves into lost histories, reclaiming spaces from which we and our marginalized peers were systemically left out.[3] I’m glad when the works sometimes flop and fail, or when they turn you up and turn you on, like a great night of drag.[4]

Pass-through, 2020. Acrylic and ink on denim and twill fabrics, with overdyed denim and twill; cut and sewn. 54 3/8″ x 72 1/4″.

*

The art museum I once worked at was located inside of a shopping mall. My office was a repurposed closet, just behind the exhibition galleries. I had scores of opportunities each day to interact with visitors and to revisit, in short glances and long looks, the works on display.

I curated an exhibit that included an abstract painting[5] by the late, great Louise Fishman. One day a man, dressed in business casual, stopped me, fuming about Fishman’s work. He pulled a pen from his pocket and placed it on the floor with flourish (it’s not just the queers who are dramatic). “If this is art,” he said to me, pointing to the painting, “than so is this,” he concluded as he gestured to the pen on the floor. “It is if you want it be,” I replied. If abstract painting could cause that much ruckus, I would have to make abstract paintings.

When I first looked at that Fishman painting, I wasn’t sure I liked it. In “Cautionary Advice from a Lesbian Painter,” (1977), Fishman wrote that, “I’ve learned that a quick look can be very damaging. You often see very little of a painting in a quick look…[6] For months, over and over, I took in her painting in that exhibition, and it slowly got better and better, one view after another, talking to me, speaking in layers, until it lodged its complex surfaces under my skin, revealing its marks and secrets on a timeframe that I needed to absorb, inside me, and adapt towards.

– JVD, October 2021

Through & Through, 2013/21. Pigment Print. 8″ x 12″. Edition of 1 +1 AP.

[1] “The discontinuity of queer desires can be explained in terms of objects that are not points on the straight line: the subject has to go ‘off line’ to reach such objects.” Sara Ahmed, Queer Phenomenology (Durham: Duke University Press, 2007) p. 71

[2] The full quote: ”No artist has a pre-emptive claim on the tax dollars of the American people to put forward such trash.” Senator Jesse Helms, speaking on the Senate floor, July 27, 1989.

[3] Heather Love, Feeling Backward: Loss and the Politics of Queer History. (Boston: Harvard University Press, 2007)

[4] Jack Halberstam, in The Queer Art of Failure (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011) writes: “This is a story of art without markets, of drama without a script, narrative without progress. The queer art of failure turns on the impossible, the unlikely, and the unremarkable. It quietly loses, and in losing it imagines other goals for life, for love, for art, and for being.”

[5] The painting was titled April, and dated 1998.

[6] Reprinted in Art & Queer Culture, ed. by Catherine Lord and Richard Meyer (New York: Phaidon Press, 2013). pp 317-318.

Jonathan VanDyke is a New York City artist working at the intersection of painting and performance. Solo exhibition and performances have appeared at The Columbus Museum in Georgia, 1/9unosunove in Rome, Loock Galerie Berlin, Tops Gallery in Memphis, Four Boxes Gallery in Denmark, Storm King Art Center, Este Arte in Uruguay, The Power Plant in Toronto, and The Albright-Knox Art Gallery. His work has been featured in many group exhibitions, including Queer Abstraction, a landmark survey at The Des Moines Art Center. He leads workshops focused upon embodied practice, presented most recently at Mount Holyoke College, Dickinson College, The University of Alaska, and The Museum of the North.