Jordan Arseneault and Jon Henry

Background to the Dialogue

Jordan Arseneault was a visiting artist to the Old Furnace Artist Residency, run by Jon Henry, in late December of 2015. The following conversation grew out of various dinner and car-ride chats that meandered around the affect of socially engaged art, HIV activism, personal love experiences, rural organizing and the ethics of politically based art practice. The pinnacle of the conversation occurred atop Eastern Mennonite University’s hilltop campus during an impressive sunset. This dialogue acts to publicly record the exchange to foster citable narrative on accountability.

Introduction

As socially engaged art practices continue to be in vogue within western art scenes, we feel it important to interject body politics into the discourse; as funders and institutions like the Queens Museum, Oakland Art Museum and A Blade of Grass are rapidly shifting towards supporting, archiving, financing and publicizing such practices we hope they remain committed to supporting marginalized audiences and artists.

We are committed to a slippery definition of socially engaged art practices, which we see at work relying on social activation, audience co-creation, and communal engagement. This conversation is inspired by José Esteban Muñoz’s notion of a queer critical methodology that functions ‘as a backward glance that enacts a future vision’ and Jack Halberstam’s idea of failure in the Queer Art of Failure: ‘this failure, hilarious in its execution, poignant in its meaning, and exhilarating in its aftermath, is so much better, so much more liberating than any success that could possibly be achieved in the context of a teen beauty contest,’[1] or in our case, non-profit academic publishing.

Social practice as u-pragma or a ‘non-thing’ is one of our starting points. Working from the standpoint of a Halberstamian ‘failure,’ we are ambivalent about the insufficiency or porousness of this working definition. We were asked to propose one, and this is what we came up with for the purposes of this piece. If utopia were a ‘no-place’ then we would propose that a lot of socially engaged art deals with being u-pragma or ‘not a thing’ (from the Greek u meaning non and pragma meaning ‘thing’). We think this is one of the reasons that in social practice, attribution becomes slippery, and often the need for it slips away. This does not mean that attribution and objecthood cannot be imagined, experienced, paid for or appropriated in social practice, but it is difficult for socially engaged art to be bought, sold or owned, at least in the same way that other so-called ‘intellectual property’ is. This is one of social practice’s many challenges and opportunities. If Nato Thompson calls socially engaged art a ‘mess worth making’,[2] we hold that this very ‘mess’ is in fact a deliberate blurring of categories and shirking of spectatorial expectations. While most art can provide an object, a passive experience, or an ephemeral image (think GIFs), social practice trades in dialogue, process, active experiences and non-object-based outcomes. One could, for instance, grow a garden with people and have a garden be the output: however, the garden is not the social practice piece. Rather, the exchanges, the narratives and process of planting and tending to it would be. This is why so much of social practice seems to be performative, durational or just plain hard to document. (In 2015, Jon grew tomatoes with queer Mennonites who had been shunned by their families. The tomatoes were delicious, but the red fruits were not themselves the art piece The Tomato Project. Rather, the process and experience of the growing was.)[3]

Jon Henry, The Tomato Project, 2016. Photo courtesy the artist.

Jordan Arseneault: First of all, let me start by saying how I would not like this conversation to go: Carlos Motta and Nathan Lee’s conversation for the We Who Feel Differently online journal: ‘there is tremendous ferocity in being gentle.’[4] The challenge of this article for me was that Motta’s feelings and musings about pre-exposure prophylaxis were given equal ink and weight as Lee’s (who is HIV-positive). Even though the intent of this interview/article was to show that there is a common ground of conversation about HIV and treatment-as-prevention that allows negative and positive gay men to talk candidly, the effect, disappointingly, seemed to make Motta’s account of his experience somehow more artful: that the fact of PrEP making him now immune to serophobia (the irrational fear of HIV-positive people that leads to stigma and is based in prejudice) makes Motta some kind of post-modern übermensch of tolerance (he has conquered his fears, wielded his dangerous desire on the wings of Gilead’s blue pill, and now shares about it).

My participation in this article has a two-fold purpose of getting people to be more thoughtful about their HIV/AIDS social practice, and to dismantle the system of stigma and oppression that we wittingly and unwittingly uphold as gay male artists in the human-immunodeficiency-viral era. I am here to say two things as provisos:

- You, reader, are probably complicit in HIV stigmatization in some way;

- Your social/art practice, if it is art, and if it is thoughtful enough to be called a practice, needs to listen to oppressed communities that you work with foremost, otherwise, choose another hot-button social issue to meddle with in said practice.

Jon Henry: Well now that we have established some ground rules, I wanted to establish some frameworks related to art. Within our post-Duchampian world where everything can be re-contextualized as art, do you think any activity can be made into a form of social practice? And if so, what if artists formed their own hospitals?

JA: Definitions of what is or isn’t art are used to cement power and legitimacy. If artists formed their own hospitals to treat only other artists—I think this would be allowed in some countries—but would probably be morally questionable (to whom would they refuse care?). I subscribe to the belief that most art requires a buttressing network (or Frame) and a self-situation in a history of making (or Discourse). If they form a hospital but don’t document it or talk about it in their artist CVs or get arts grants to do it or call it art or let Centers of Power call it art, then that would just be a bunch of artists who happen to run a hospital (fittingly, medicine is still called a ‘healing art,’ is it not?). If the running of the hospital is supposed to be some kind of art project, with a proper title such ‘Healing Art’ or ‘Art Hospital,’ then that would be really weird and fraught with problems of inclusivity, confidentially, conflict of interest and sustainability. Social practice can be a lot of things, but a lot of things can’t be legitimate social practice, in my view. If someone wants to get a NEH grant to go run a hospital for artists run by artists, good luck finding the millions a year it takes to run a hospital in the global north. If you do it in the developing world, where your money would go further, then huge questions need to be asked of what patients have to give, and what they receive in return. It’s an interesting thought experiment: underlying it is a hypothetical reductio ad absurdum of where we draw the line between art and not-art. For me, the categories are always about ego, documentation and institutional (network) legitimacy. If you’re running an X socially-beneficial project without the need for personal credit, documentation or having it be called ‘art/social practice’ by your peers/critics/funders, then you’re not doing social practice. You’re just running an X. Which could be cool. Maybe we should all go do that.

JA: I hear you want to make an HIV testing site as an art project. Can you tell me where this project came from, and what it’s about?

JH: When I moved back to Virginia from NYC, I couldn’t find a place for a free HIV test. I re-realized that there existed an urban/rural divide around HIV access, resources and education. As an artist, I am particularly intrigued about fracturing up what art institutions might do and offer. So, I wondered about developing an HIV testing outreach program at our local community non-profit art gallery; I approached the gallery and they wanted me to submit it as an exhibition. I began to think and research how a Rapid Oral HIV Test might appear as an art project since I was encouraged to add more layers because just providing a free rapid oral test wouldn’t be art. I was particularly interested in the stressful 15-minute waiting gap and thought of offering some form of free bodywork during that period along with a better ‘installation’ in the space of the sterile clinic environment. I was planning to bring in an outside testing group and support organization that I organized within the past. However, the project never came to fruition, in part because I felt uneasy and unresolved about the project, the danger of it becoming a slippery spectacle. At the time, the only critical feedback I got from my faculty was to look at the Center for Tactical Magic’s blood donation project.[5]

JA: Do you think universities inoculate art and render it useless for social change? Or are they useful funding funnels for doing relevant work in a world that doesn’t care about the stuff we care about?

JH: For sure, universities do inoculate and blunt art when it comes to social change. Yet, I find that in my community it’s a worthwhile effort because my university hoards funding streams and actively absorbs funding streams into its ‘community management and support’ offices. Based upon my own capacity, it seems more viable to engage them. As universities continue to buy up real estate in our cities, I find it useful to access them to get free space for large gatherings or events. I still think it’s important to develop networks/support outside of institutions so we can survive if these systems don’t care about the stuff we care about. I usually don’t take the approach of ‘yes or no;’ compromises are a reality of getting the work done. Instead, let’s consider how might communities pillage such institutions?

Finally, I think university is where many folks become politicized. During my undergrad years, I became invested in our university’s LGBT advocacy organization. It taught me a whole lot about politics, organizing, activism and history; yet, it wasn’t until I was in grad school that I got or realized the approval to wed art and activism together.

Jon Henry, Untitled Bag (documentation), 2014-present. Performance with a game/butcher bag and teddy bears.

JA: So, what’s the most interesting social practice piece you’ve seen that deals with HIV or sexual alterity or biopolitics?

JH: Adaku Utah recently got a big grant from A Blade of Grass for her healing project Harriet’s Apothecary: Summer Edition.[6] I’ve not seen the overall documentation but it was exciting to see a funder give money to a non-white artist for a project for non-white audiences. It’s particularly moving for its focus on healing outside of the traditional western practice.

I feel like most of the art related to HIV, or sexual alterity or biopolitics that I’ve seen falls more into the art as education and outreach model versus the socially engaged models. I’ve read a fair bit of the social practice canon, yet ACT-UP and its relatives are never mentioned as a form socially engaged art. To me, it totally is/was the proto-example of social practice! I assume its erasure is because it doesn’t have a clear artist persona at the helm? But more poignantly, it’s probably because of serophobia.

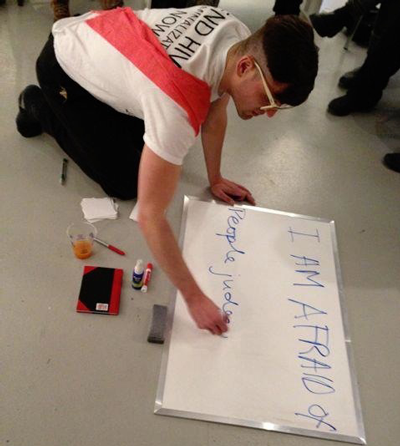

While in school, I realized I would have to become my own teacher since there weren’t many queers in my institution, along with people of color, women and radical leftists. As I began my investigation into the social practice field, I saw that artists might enter into contexts or communities to uplift voices, help folks out, or develop resources in the place. Yet, the artist might not be connected to that community or issue. I wonder if you have experience with this in terms of your experiences around HIV and art?

JA: Most of the time artists mine HIV-positive communities or other marginal groups for pathos and to lend their project the patina of having a liberal social conscience. One photographer contacted me recently to help him find ‘HIV-positive children’ to do a portrait series of. I was so baffled by how he thought this would help anyone but his career that I just never responded. Typically, such artists have a vague, shallow, understanding of how much they are doing these ‘goody two-shoes’ projects just because it will bolster their careers. But as for social practice per se, the reason that most of these projects don’t work is that very, very few artists are willing to share credit and profits (material or cultural capital) and very few participants see the benefit beyond the typical ‘this will help Mainstream People see my community is a better light.’ I refer to this kind of art practice as ‘Missionary Style’: the artist comes in with money, the promise of exposure, institutional recognition, or ‘moral publicity’ (the ability to get their sordid, sad messages across to an uncaring, inchoate mainstream ‘they’). In return, the ‘colonized’ participants provide sad stories, quirky ideas and free content for the Missionary Artist.

If the participants are lucky, they might learn to use Final Cut Pro or get free snacks. Most of the time they get to hang out with like-minded people from their community and make fun of the artist, which can be its own dividend. The best social practice is usually by-and-for. But then there are famous examples of artist facilitators and projects like Suzanne Lacy’s The Roof is on Fire (1994)[7] and Jessica MacCormack’s We Become Our Own Wolves (2007)[8] where the participants ‘gained’ something such as talking about police harassment and having authorities be forced to listen, and animating their own videos about women’s experience in prison, respectively. In these and many other examples, the artist/facilitator lent active, marginalized participants the exposure and tools that they would not otherwise have had due to systemic oppression (of black teens and incarcerated women, in these examples). Developing resources is key. Participants walking away merely being able to say they were part of someone’s MFA project is #artfail #badsocialpractice. Most social artists think they’re doing more good than they’re actually doing. I recall someone who made a film about women and HIV criminalization. As a consequence, one of her participants was accused and charged with HIV non-disclosure and she is way worse off now.

JH: It’s interesting how ethics become such a component of the analysis, criticism, and general aesthetics of socially engaged art. Traditionally, notions of beauty are evoked when discussing art. A project’s ‘beauty quotient’ even becomes a tool for seemingly horrible causes like landscaping over a Superfund Waste site or gentrifying a ‘run-down neighborhood’ with murals. Do you worry about such effects as a result of your practice?

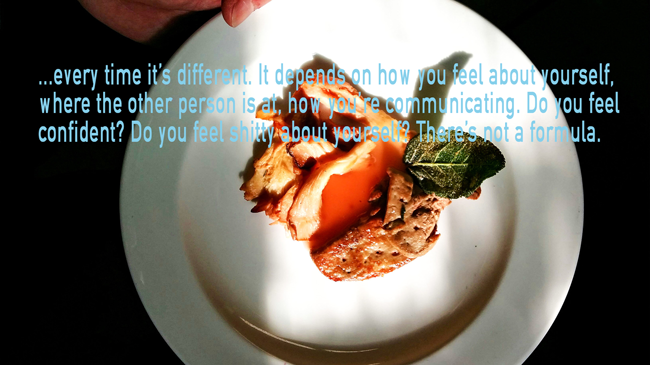

JA: I think Thompson’s ‘socially engaged art is a mess worth making,’ says it best.[9] If people in marginalized situations want help making gardens, making poster art, making beautiful useful things like playground equipment or whatever, that’s awesome. Funded artists should be asking these communities what they need, what they want, and helping out. I think when we have so much, and other people so little—we have a duty to balance things out. Getting a grant to turn a warehouse into an art gallery, as the arrow of the gentrification war machine is clearly too facile a ‘bad example’ of what we’re talking about here. Social practice is allowed to be ugly. Beauty is fun when called for, but gross when unbidden in places where real help is needed. For example, I do a workshop called Disclosure Cookbook with Toronto artist Mikiki, where we make beautiful, delicious food for HIV-positive people while talking about HIV disclosure. We take photos of the food and superimpose anonymized text from the conversation transcripts over the ‘food-porn’ style photos. We get the photos for our website and inevitably, half the participants are low-income or tend to live alone and don’t tend to enjoy expensive food in groups a lot of the time. If you want to build a flowerbed or a garden or make a mural in a community that wants those things, with people from that community, sounds fun to me!

Mikiki and Jordan Arseneault, Disclosure Cookbook, 2016, Digital image.

JA: While in residency at the Old Furnace Artist Residency (OFAR) with you, I couldn’t help but notice how much the residency was sexually charged. And, you seemed pretty open about sex. I wonder if you could talk more about that?

JH: You aren’t the first person to mention that before. I strongly believe folks shouldn’t feel shame when it comes to talking about sex. Furthermore, as a budding young artist, I was quick to notice the informal code of conduct of the art world where personal sex lives become erased. It’s especially true when applying to residencies or fellowships where some of the only rules forbid visit by guests or partners. I for one can’t get my creative juices flowing without all the juices flowing. From the beginning, I wanted the Old Furnace Artist Residency to be a bit different from other residencies. I am fine with folks bringing their partners or hooking up with someone from the local bar. I joke—well it’s not really a joke—that our only major corporate sponsor is Trojan as OFAR gets a bi-annual shipment of condoms from them for our public art events.

Furthermore, I’m always interested in pushing the limits, I think they use to call it avant-garde but my in MA it’s called being a ‘fire starter.’ Either way, I became interested in the limits of social practice and based upon the prudishness of my faculty and the general art world I recognized it to be sex. So I began to organize a variety of sex parties, orgies and group situations at my home that were billed under the auspice of social aesthetics. It didn’t seem ethical to create visual documentation of the work since the other folks had jobs, families, wives, etc. I ended up publishing a series of stories in KAPSULA magazine in their special issue Risk.[10]

JH: So have you envisioned any series of ethics or trajectory for your work?

JA: Three principles come to mind:

- Participants should know what they’re consenting to you for and should have the right to be credited as collaborators;

- There should be real benefits for the participants such that they can consent to the project and/or modify it in ways they like, rather than just ‘oh you don’t want to be documented, so you can’t be in our project,’ for example;

- It should rock the boat a little! Projects whose sole purpose is to ‘humanize’ a group that is denigrated by society (like the film a friend is about to make about sex workers) could fall short of goals that those communities have actually articulated, such as ‘repeal all laws criminalizing sex work.’ Making work that is all pathos and cuteness (see above on the photographer looking for poz children!) fail their audiences, fail their participants, and worst of all, disappoint me because they tend to stay ‘arty’ for fear of being branded didactic. We live in a society that wants to imprison people for no good reason in order to maintain a climate of surveillance, fear, racial and biopolitical injustice and poverty. How can you just want pretty portraits to counter that?

Jordan Arseneault with the SéroSyndicat, Sashes Action for Montréal AIDS Vigil, 2012. Part of Fear Drag series 2010-2016.

What about you? What does good social practice on the Internet about HIV (or sexual alterity or biopolitics) look like? Is there anything good going on online or is it just a chimeric mirror of more interesting stuff going on in real life?

JH: For starters, I see socially engaged practices as having to occupy the gray zone where the viewer wonders: is this art, social work or activism? I feel like it’s a good moniker for what typically might be called confusion. One project that has stuck in my mind was the collective Haha’s project to grow produce for HIV/AIDS patients in an abandoned storefront via hydroponics.[11] There are also various projects like Jessica Lynn Whitbread’s work with No Pants, No Problem dance parties and Tea Time.[12] Yet, I wonder if Adrian Chesser’s I Have Something to Tell You[13] or the Spread walk by Niegel Smith & Todd Shalom count?[14]

But, I get your vibe that most online socially engaged art projects are simulacra of the more interesting real life stuff. Sometimes, I see events put on by HIV/AIDS Support Organizations such as Fan Free Clinic’s RVA Remembers 2011 and see the ‘artness’ of it all.[15] That project uses the same materials of a Christo installation but it stays with me way longer due to the collaborative, non-capitalist and direct political agenda of the work. Another organization, Visual AIDS, is a prime example where institutions become a socially engaged art project unto themselves?[16]

It doesn’t deal with HIV but I’ve been really moved by Rebecca Gomperts’s Woman on Waves project.[17] The initial project didn’t really provide a large number (if any) abortions but it did garner a massive amount of press and ‘street cred.’ Since then, Women on Web has been running an online mail order program to give out abortion pills. Sometimes this work is included in socially engaged art and art discussions, and sometimes it isn’t. But for me, it’s a strong model of a project that is leading and offering change, while also challenging us mentally.

What are your general thoughts on social practice?

JA: Never stop. Ask your participants what they want/need. Be prepared to give up your art practice and just do good things for people who ask for your help. Do this because you are more privileged than them; do this because the world becomes a better place when you do this. Get into the museum/journal/university/residency if you must, but remember that you owe your participants something better than an email of thanks and some fucking herbal tea.

Jordan Arseneault, Fear Drag, 2012, Workshop documentation at VAV Gallery, Montréal.

JH: Yes, I feel like socially engaged art is a risk worth taking. We need to dream big too, Matilda Bernstein Sycamore sums it up well when she asks: ‘why did our dreams get so small?’[18]

JA: So, Jon, Ricky Varghese, the editor of this special issue of Drain, was originally interested in having you submit on the topic of risk, catalyzed by the Charging for Hot Sauce is a Sin piece in KAPSULA about the sex parties you organized that year.

JH: Well, I did get invited to submit for this journal issue on HIV/AIDS and memory after a series of my sex orgy stories were published, as you said. The stories didn’t deal with HIV nor do I currently have it and I also always practice safer sex; Trojan is actually one of the indirect sponsors of OFAR. Anyways, at the time, the only critical feedback I received from my academic advising team was about the risks I was facing re: STIs. I began to think more about why folks make this connection, and if it just arose out of my MSM (men who sex with men) practices?

I am uneasy to quickly dismiss social practice, since funders and institutions like the Queens Museum and A Blade of Grass are shifting towards supporting it. Social practice folks need to stop wasting energy arguing inclusion into the art world, Rick Lowe received a MacArthur ‘Genius Grant’[19] and Tania Bruguera was the keynote at the College Arts Association Conference’s 2016 gathering in Washington, DC.[20] I sense—at least in the USA—that there will be more funding directed towards this art form as we continue to gut social welfare programs. Funding begins to get shifted from public institutions towards public-private collaborations or grants, and neo-liberalism excuses these practices under the auspice of social-capitalism. For example, I’ve seen many artists developing after-school art classes but not advocating for these programs within the schools as they get cut. Claire Bishop outlined a similar trajectory of causes when describing the rise of the UK’s community arts programs in her book Artificial Hells following Thatcher’s war on the UK’s social welfare programs.[21]

JA: If Bishop described ‘artificial hells’ how can we sit with u-pragma, utopias and artificial happy-places? Can social practice, along with Belinda Carlisle, say that ‘heaven is a place on earth’?[22] How do we make social practice more aspirational and at the same time, more responsible?

JH: I want to see my fellow artists not only engaged in the gallery but in their city hall. I think if we want to actually enact our dreams and visions, we have to engage with some of realities’ components. I think that’s always where social practice gets fuzzy since it relies so heavily on the u-pragma. We can continue to exist, i.e., foster this praxis within that mode of being, but we should be conscious of our place within the ecosystem.

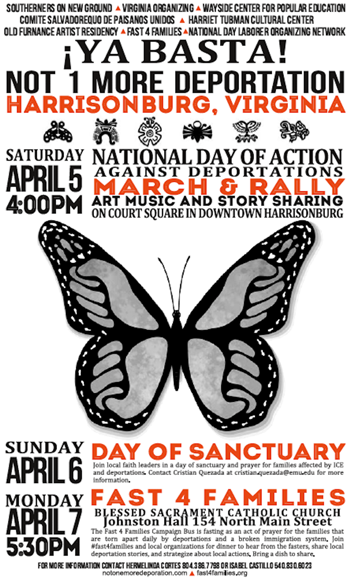

Jon Henry, YaBasta: Not 1 More Deportation, 2014, Protest flyer.

You started our conversation with a quote from Nato Thompson so it only seems fitting to end with another. He notes that the conservative movement or ‘right wing’ can easily usurp our liberatory ideals like grassroots organizing towards more invasive modes of military occupation or police oversight.[23] So I do want to remain vigilant about the field and acknowledge that our u-pragma can still be absorbed into the spectacle. However, I recently saw Angela Davis speak at Open Engagement and it was noted that the Black Panther Party’s cultural capital might have waned; yet their principles live on as they have been widely enacted (such as every school in America now offering free morning lunches). Thus, our aspirations will have an effect upon real life, yet we need to be cognizant of unintended consequences and develop systems of ethical development. Artists need to be risk-takers, but like Evel Knievel, let’s be sure to have some landing pads, assistance, safety equipment, advisors, etc. Based upon my recent attendance at Open Engagement where there was a plethora of diverse and engaged presentations of social practice artists, I not only have hope but also have seen evidence of our aspirations being realized. Belinda Carlisle does remind us that we (can? should? must?), nay will MAKE heaven a place on earth. Let’s get making!

[1] Halberstam, Jack. The Queer Art of Failure (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011).

[2] Thompson, Nato. ‘Socially Engaged Art is a Mess Worth Making’ in Spontaneous Interventions, 2012. http://www.spontaneousinterventions.org/reading/socially-engaged-artis-a-mess-worth-making.

[3] The Tomato Project (2016) by Jon Henry. Site specific, Harrisonburg, Virginia, USA. http://tomatoetomatoproject.tumblr.com.

[4] Lee, Nathan and Carlos Motta. ‘There is Tremendous Ferocity in Being Gentle’ in Kerr, Theodore (ed,). We Who Feel Differently Journal, 2014.

[5] The Center for Tactical Magic, 2002. http://www.tacticalmagic.org/CTM/project%20pages/SACred.htm.

[6] Utah, Adaku, A Blade of Grass. http://www.abladeofgrass.org/fellow/adaku-utah/.

[7] Lacy, Suzanne, Annice Jacoby and Chris Johnson. ‘The Roof is on Fire’ (1993-1994) from The Oakland Projects (1991-2001), site specific, Oakland, California, USA. http://www.suzannelacy.com/the-oakland-projects/.

[8] MacCormack, Jessica. We Become our own Wolves (2007), collaborative animation and mixed media. Kingston, Ontario. http://jessicamaccormack.com/2013/09/we-become-our-own-wolves/.

[10] Risk, Kapsula Magazin, 2015. http://kapsula.ca/releases/KAPSULA_RISK_1of2.pdf.

[11] FLOOD. HaHa Collective. 1992-1995. http://www.hahahaha.org/projFlood.html.

[12] Whitbread, Jessica. No Pants No Problem & Tea Time (2012-present), various locations. http://jessicawhitbread.com/projects/.

[13] Chesser, Adrian. I Have Something to Tell You. 2004 http://www.adrainchesser.com/i-have-something-to-tell-you/.

[14] Smith, Niegel and Todd Shalom. Spread. Elastic City, 2013 https://www.elastic-city.org/walks/spread.

[15] Health Brigade. RVA Remembers, 2011 http://www.fanfreeclinic.org/2011/12/29/rva-remembers-2011/.

[16] Visual AIDS. Founded 1988, New York City. https://www.visualaids.org.

[17] Gomperts, Rebecca. Women On Waves and Women On Web have merged together. The project began in 1999. http://www.womenonwaves.org/.

[18] Meronek, Toshio. Truth Out, 2015. http://www.truth-out.org/news/item/28430-human-rights-campaign-under-fire-in-lgbt-community.

[19] Lowe, Rick. MacArthur Foundation, 2014. https://www.macfound.org/fellows/920/.

[20] Bruguera, Tania. College Arts Association. 2016 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vdEEKwFrqFY.

[21] Bishop, Claire. Artificial Hells (New York: Verso, 2012).

[22] Carlisle, Belinda ‘Heaven Is a Place on Earth’ (1987), 4 min, MCA Records. Lyrics by Rick Nowels & Ellen Shipley. Produced by Rick Nowels.

[23] Thompson, Nato. ‘The Insurgents Part 2’. E-Flux, 2013. http://www.e-flux.com/journal/the-insurgents-part-ii-fighting-the-left-by-being-the-left/.

Jordan Arseneault is a performance artist living in Montreal, Canada. He focuses on issues of HIV, body dysmorphia and inherited trauma within his practice. When not arting, Arseneault organizes with the SéroSyndicat/Blood Union.

Jon Henry is an artist and organizer based in Harrisonburg, Virginia. He manages the Old Furnace Artist Residency, which focuses on supporting social justice-based art practices. OFAR is hosted within Henry’s home, so there are many intimate encounters and conversations between Henry and visiting artists. More info and documentation of the Old Furnace Artist Residency is available via: oldfurnace.tumblr.com.