Joshua West Smith

Plan of the labyrinth of Chartres Cathedral, Chartres, France. Research image.

Athleticism and Art. They are not wholly dissimilar undertakings and they do not stand apart in the canon. Athleticism is obtained through a practicing, a methodical indoctrination into the particular discipline, a honing of one’s skills and a pursuit of improvement. The artist practices, studies, hones and improves.

The body pushed, measured, and possibly broken. Jackson Pollock’s gestures, Carolee Schneemann’s bodily entanglement, Tehching Hsieh’s epic durations, Matthew Barney’s restraint, Marina Abramović’s method. The move to acknowledge time—and the body in it—is not new. And, it is easy to retain or possess one’s integrity when the artist is both the maker of the spectacle and its performer. But, to shift the gaze away from one’s self and scrutinize other bodies while allowing them to retain their dignity is a high wire act that requires a particular sensitivity.

Anna Wittenberg is an artist who utilizes a number of artistic methodologies to actively explore our world. Her studio is full of drawings, photographs, sculpture, and an inordinate quantity of notes and preparatory sketches. On the floor of her studio stretching from wall to wall is what, at first glance, seems to be some type of plan view of an ancient Basilica—or is it one half of the iconic lines of a basketball court defined in blue tape? Her practice is varied but the results invariably have a specifically wry wit about them which leaves space for the viewer to occupy the novel role of spectator.

Joshua West Smith: Do you think we can both try to use an unfortunately large number of sport related metaphors and puns in this conversation?

Anna Wittenberg: Well Josh—you miss a hundred percent of the shots you don’t take…

JS: Home court advantage often leads to a win in professional sports. You’re an artist who seems to exemplify an interdisciplinary practice while investigating things from a similar perspective. Do you have a home court and can you describe it?

AW: I suppose I’m increasingly interested in context. I search for structures, be they antiquated Cathedral processionals or overused Hollywood tropes, and through a bit of reframing, propose an alternative. I’m not a studio artist so I am a little hesitant to answer your question outright because, like Freud, it’s a homelessness that I’m drawn to. But, in an effort to play ball, I would take an away game any day over the home court.

JS: Training often manifests in athletics as a preternatural ability that seems to bypass consciousness. Disengaging one’s brain is essential for the basketball player who hits a running three pointer off of one foot with a hand in their face, the track athlete who runs her/his fastest 400m, or the dancer flying high above the stage executing the perfect grand jeté. How do you think turning your brain off and relying on intuition and your training is a part of your artistic practice?

AW: Right – if I remember psych 101 correctly I think they call that ‘flow’. I’ve always enjoyed that term. It described a secretary as being in ‘flow’ when deftly sorting files for hours, a bit of a condemning anecdote, but I digress. Since I don’t have a particular medium in the classical sense, I don’t have many pure ‘flow’ moments, which is something I have always envied in others’ practices. Outside of sketching and occasionally video editing, some of my most exciting, less self-aware moments are when I have about 30 tabs open in my browser, a billion post-its going and I’m constantly replacing the ink cartridge for my printer. The alchemy of combining structures is intoxicating, and is a process that occasionally yields some pretty unexpected results.

David Light, 2015, Inkjet Print. 22 x 30 inches.

JS: When I think about athleticism I think about the body. People populate the majority of your work I have noticed. From strange, exploratory works like “David Light,” which is a disorienting photo of the top of a man’s head, to your video piece “KJMP Presents Der Sandmann” in which a female barbershop quartet performs through the veil of slowed audio and video, which hyper accentuates every bodily gesture and auditory expulsion. This type of work, which prompts a scrutinizing of the subject, can lead to cold objectification—or worse—a comical and judgmental portrayal. Your work deftly avoids these pitfalls and invites me to immerse myself in the spectacle while regularly checking back in with the performer at an empathetic level, which acts to humanize them. This seems to allow the performers to retain a fuller self through your sensitive portrayal of them. Can you explain some of your concerns in regards to working with players or actors? And what are some of the similarities and differences you see in how ‘David Light’ and ‘KJMP Presents Der Sandmann’ came to be and exist in the world?

KJMP Presents Der Sandmann, 2014, Video still, 8’26”.

AW: It is unpredictable working with people and it does involve a certain amount of risk if you don’t script things out. I avoid using actors to portray a specific person, which means I lose the security of distance through illustration. It also means however, that you can profit from the fruits of a certain type of collaboration. I am not saying that I don’t set the stage and dictate the actions, I just encourage the ‘players’ to do what they will within that space, and carry themselves the best way they see fit. I have now made a couple of works where the players are people that are doing what they already know how to do, such as a drummer drumming, or in the case of KJMP, four women from a senior female barbershop quartet singing one of their standards, or in ‘David Light’, a Santa Claus character actor getting his portrait taken.

‘KJMP Presents Der Sandmann’ grew out of an interest in the Sandman. I was curious how this figure, a bringer of sleep, has persisted through so many iterations of popular culture and still maintains its shadowy interest and mystery. The title of the piece reflects the name of the quartet and the title of ETA Hoffman’s 1816 version of the character in his short story Der Sandmann which depicts the first alternative depiction of the Hans Christian Anderson character as an evil boogie man who steels naughty children’s eyes—a work Freud then analyzed. The quartet sang The Chordette standard ‘Mr. Sandman’ at 60% speed, which I then further slowed in an effort to draw out this elusive yet persistent mystery.

‘David Light’ also stemmed from an interest in a popular cultural icon that began with a Craigslist ad for a Santa Claus. The formal intervention in this case was much simpler and only required a simple bowing of the head. The title of this piece also reflects the actual name of the person portrayed.

JS: One of your most recent works called ‘Peregrinus’ manifested as a performance and involved the choreographing of two female basketball players who processed into a gallery with the lines of a basketball court depicted in tape on the floor. The two players executed a series of synchronized movements: dribbling, circling and eventually exiting. the gallery. The power of this piece seemed to lie in its presence and physicality, the slightly awkward but highly competent movements of the players, and the mesmerizing auditory synchronization of the bouncing basketballs. Comparing this piece to your previous works of video or photography, what interests you?

AW: To reference a couple of the previous questions, ‘Peregrinus’ was an experiment in both context and flow, or in structure and meditation. I was curious what would happen if I mapped an antiquated form, an early Cathedral processional, onto a contemporary context, the gallery space, and employed ‘professional’ Division I basketball players to carry out the action. This particular decision, working with real basketball players, felt in keeping with my current interest in working with people who ‘do what they do’, reconfigured within another structure I propose. The main departure for me was that the performance was live and the players were rather close to the audience; a shift in form and proximity. There seems to be something a bit ineffable about being close to a body performing an action with total strength and confidence. In this case, the action was dribbling, which has a striking percussive quality. My interest was that such an action repeated can lead to a similarly meditative mental zone as that of the players in flow.

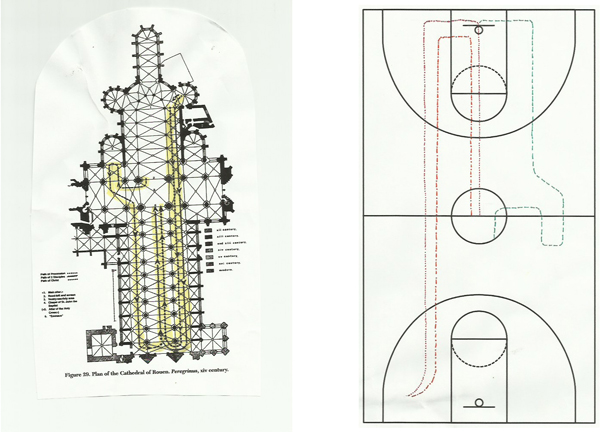

(Left) Plan of the original Peregrinus processional in the Cathedral of Rouen, Rouen, France. Research image. (Right) Peregrinus processional path mapped onto diagram of a basketball court. Research image.

Now, the context: I have recently been interested in early Medieval processionals, when church services first started incorporating processionals and small ‘scenes’ depicting various biblical stories in order to stimulate attendance to the church. There are beautiful floor plans of cruciform cathedrals with little hash marks depicting the various trajectories of the processors, reminiscent of contemporary game plans. The pathway the players walked in this performance was that of an early pilgrimage play called the Peregrinus that featured two pilgrims who inadvertently meet Christ. The two basketball players stood in for the ‘Wayfarers’, and instead of meeting Christ, they walk a paired down version of a Cathedral labyrinth whilst dribbling. Wandering and meditating are interests that I am currently exploring, but the conflation of the spectator in the church, the spectator at the basketball game, and the spectator in the gallery strike me as fertile ground for exploration.

Peregrinus, 2015, Performance, 10′ (approx). Image from performance.

JS: I always love getting reading recommendations from people. Can you share five book titles that either relate to what you’re currently thinking about or are on your must-read list?

AW: Right now I’m reading a great biography about Athanasius Kircher called A Man of Misconceptions by John Glassie. If you don’t know about Kircher, it’s worth a Wikipedia search. He was a hyper curious 17th century Jesuit priest from what is now central Germany. Kircher proposed some incredibly beautiful and poetic—albeit usually incorrect or incomplete—hypotheses into just about every area of study.

For a project I’m working on, I’m reading a pretty incredible account of the giant volcanic eruption of Krakatoa in 1883. It’s called Krakatoa: The Day the World Exploded. The eruption of Krakatoa is the loudest sound in recorded history. The blasts created shock waves that went around the planet 7 times and it changed the earth’s temperature for several years. Apparently it also created beautiful green sunsets—pretty wild.

For my general edification I have Kaprow’s Essays on the Blurring of Art and Life and Hakim Bey’s Temporary Autonomous Zone on the docket (I’m behind the times with those!)

Other than that, I recently read a great book on relic theft in the early Middle Ages called Furta Sacra by Patrick Geary. Turns out, what’s sacred and what’s lucrative are not mutually exclusive! What a shocker right?!

JS: I know this kind of question oversimplifies what an artist is really doing, but I’ll ask it anyway… Can you briefly express what you would like people to take away from your work?

AW: I’m a big advocate of curiosity, and mystery is one way to encourage curiosity. I play with structures and conventions. So through some mysterious combination of deconstruction and theatricality, I want to activate an engagement with structures or systems that we may take for granted, that are buried deep within the social construct or that have been altogether forgotten.

Anna Wittenberg (b. 1985, Houston TX) is an interdisciplinary artist based in Los Angeles. She received her BA in Media Studies at Pitzer college in 2008 and is currently working toward her MFA at University of California Riverside. Coming from a background in film and critical theory, Anna primarily works in video, performance and photography to interrogate facets of both contemporary and historical cultural practices. www.annawittenberg.com

Joshua West Smith is an artist and curator who lives and works in the Inland Empire of Southern California. Smith’s work has been exhibited nationally and internationally at venues including the MarinMOCA in Novato, California, K Space Contemporary in Corpus Christi, Texas, The Contemporary Craft Museum in Portland, Oregon, and Gallery Maskara in Mumbai, India. He has been a visiting artist at University of Wisconsin-Stout and at Whitman College. Before returning to school Smith worked as a welder, fabricator, and machinist specializing in hydraulic and pneumatic cylinders. Currently, Smith is one half of the curatorial team TILT Export:, an independent art initiative with no fixed location, which works in partnership with a variety of venues for its exhibitions. Additional work can be viewed at jjfab.com.