Lydia Rosenberg

All images by and courtesy the artist.

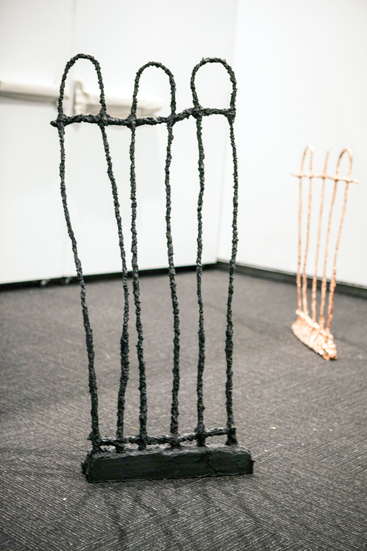

Imprecision after A.G. (detail), 2013, Paper pulp, plaster, graphite, steel. 20 x 4 x 47 inches.

All at once, the essay, the biography, the peripheral slippages, the coincidence, the remembering and the assumption take form. I know I am asserting a hefty amount of pressure to the withered gate. I also know that reading one section of an autobiography and reading the highly abridged version on Wikipedia is no recipe for scholarly acuity. During this time I have become a transmitter or an unfilled frequency on a radio, picking up and dropping off the signals as they slide in and out of audible reach.

When I picked up Primo Levi’s, The Periodic Table I thought I would be reading about chemistry—a subject I know little about but enjoyed more so than other sciences in school.

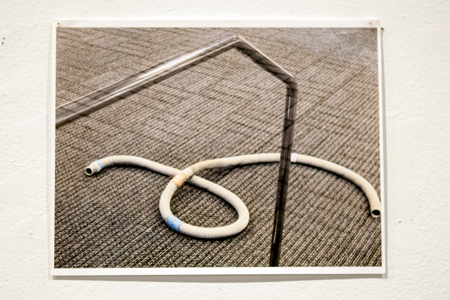

untitled intake, 2013, Inkjet print on paper. 8.5 x 11 inches.

Inset Access Only, 2013, Cast concrete stone, cotton rag paper, mini projector, aluminum, video (23min). Dimensions variable.

And it was a kind of chemistry—a chemical frequency that quivered and shook me to a deeply experienced questioning of the limits of material, of the deception of time and of newness (youth and its ecstatic wonderment) and the ultimate exposure of the impossibility of forever. From the passage entitled Hydrogen, Levi describes his noble sixteen-year-old self and his untainted idealism exclaiming, ‘I will find a short cut, I will make a lock-pick, I will push open the doors.’[1]

Incident, 2013, Paper, wood, glue. 60 x 24 x 118 inches.

I knew when I read it that these particular doors would change for me and I would focus too intently on them and that I would yet again be lifting valuable poetry out of its context, belittling its gravity with my foolish fixations. But it didn’t stop at the doors and I started seeking out these points of contact, the things I touched daily and that, by some chemical process had taken on particular qualities through my own kind of architectural anthropomorphism. A split hair of a second and the benefit of blurred vision or of peripheral distortion and the handrail became the serpent, the rusted steel gate as the stand alone figure, isolated and crudely formed, morphed in that split moment into a Giacommetti-esque form. I became aware of their failures as objects, that their own apparent concreteness was a result of a particularly skewed sense of time. These objects held a materiality that was sufficient for my own personal time but the durability of these metal and wood and plastic parts would not survive the timeline of the mountains or the oceans.

Hydrogen, 2013, Cotton rag paper. 50 x 8 x 3 inches.

An unstable material life—like an unstable memory—cannot be retained in a photograph or description of the thing: distortion and thus deterioration lies at every turn of attempted preservation. It is evident that preservation herein is an ambition of retaining the confluence of the various points that inevitably results in the production of an entirely new set of fragile and unfixed points which by now have already passed the point of newness.

Imprecision after A.G. (installation view), 2013, Paper pulp, plaster, graphite, steel armature. 20 x 4 x 47 inches.

Hydrogen (installation view), 2013.

[1] Primo, Levi. Periodic Table. Trans. Raymon Rosenthal. (New York: Schocken, 1984).

Lydia Rosenberg is a visual artist born in Pittsburgh, PA. Rosenberg has been included in several group and solo exhibitions throughout the US. She is the co-founder of H. Klum Fine Art, formerly an exhibition space in a one room apartment in Portland OR. Rosenberg currently lives and works in Philadelphia, PA where she is a candidate for the MFA in Interdisciplinary Art at the University of Pennsylvania. In 2014 she published works with Amur Initiatives and Eights, and was awarded a fellowship as artist in residence at the Vermont Studio Center.