Natasha Chaykowski

All images by and courtesy the artist.

In this age of biomedical ingenuity, which sees the wholesale embrace of cosmetic procedures staving off bodily wear-and-tear and soaring (Western) life expectancy thanks to remarkable feats in engineering and healthcare, reckoning with ruin is an altogether avoidable endeavour. Joshua Vettivelu takes up such ineffable material in his practice, querying the vulnerability of flesh and the malleability of his materials. What follows is a brief introduction to Vettivelu’s work and some of the themes that compel his practice.

Natasha Chaykowski: Could you describe your work and some of the underlying themes and issues that inform it? Are there continuities among the works that make up your practice? If not, can you speak a bit about this?

Joshua Vettivelu: The joke I constantly love to make is that I am an artist because I love to masturbate; so much of how I arrive at artworks comes from a really vigorous kind of navel gazing. Seemingly disparate things like sexual encounters, sprouting new body hair, or remembering the knee pain I would get while kneeling in church become subject to compulsive magnification. The most quiet and traumatic conversations I have with myself can be opened up to things that extend past my body and into the realms of history and power and so on.

At this stage in my career, I don’t consciously think about having a cohesive body of work. I’m much more interested in pursuing my curiosities and anxieties. I’m sure some of the work pulls from similar threads; however, this only becomes more apparent/important in retrospect. I don’t know if this makes me a lazy artist or if I’m shooting myself in the foot because it certainly makes talking about my work kind of difficult: a conversation is always preferred over a sound bite. If I were to posit a very general point of departure for my work it would be the uneasiness that accompanies having a physical body, and the lack of available language for expressing this discomfort. I’m much more comfortable with grunting and wild hand gestures than sentences and syntax.

Work in progress: various wax castings (studio view), 2014, Foundry Wax.

NC: So much of your work formally addresses the body and, in particular, fragments of the body. What inspires you to artistically treat the body in this way?

JV: I arrive at the body for many reasons. Sometimes the connection is immediate and direct and other times it is only through the process of making the object that I realize the relationship. Whatever the process of arriving, there are three main ideas that are always cycling through my head while making (though they are not always so separate in the moment).

Materiality of the House

I consider the internal body to be an unknowable and imagined space that houses and attempts to reconcile narratives about the self. These narratives, which incorporate history, desire, longing, loss and intimacy, all coalesce to form a subject position that experiences the world through a physical body. These big immaterial narratives are experienced viscerally but seem to happen in excess of the body. I am interested in bringing these narratives back into physical terms by using materials familiar to sculpture (sand, wax, clay, etc.). By distilling this feeling of excess into object and image, I am able to look at the material conditions that produced them.

Fragments and Proximity

I tend to work with fragments to resist this idea of the body as a singular, complete unit. For example, in Body Coins (2012) I created ceramic impressions of my body. Through the act of touching a material object is created from the space between fingers and skin. The installation presents the body as fragmented: the entirety of the subject cannot be physically rendered in full. This process becomes a metaphor for the formation of subjectivity, wherein external signifiers intersect to produce a readable social body. This formation of a social body creates an interior identity that is both part and parcel to the external identity that informs it. The internal psychic body, the external physical body, the external cultural body, and the internal biological body all become linked in a sort of Borromean Knot; they cannot be separated or rendered in totality. My relationship to the fragmented body becomes one of proximity, oscillating wildly between a closeness that creates a monolithic partialness to a distance that provides only a blurry totality in the horizon.

Body Coins, 2012, Ceramic. Dimensions variable. Photo: Laura Whelan.

Rubbing One Out (Casting), 2014, Bronze.

Ego

I’m very interested in the idea of ego and what it means to replicate my body (in a state of partialness) in physical form. I recently made a casting of my head in bronze. The initial idea was to create a bell or singing bowl out of my head. I wanted to use the physical properties of bronze to acoustically reverberate outward. I was thinking about childhood memories of visiting cathedrals and shrines and being obsessed with the way objects like reliquaries and statues could emit an aura of reverence; they embody spirituality in physical terms.

After receiving my bronze from the foundry I sat for a long time with this heavy head in my lap, feeling the weight of it, feeling incredibly self-indulgent. In perhaps my most expensive masturbatory act to date, I accidentally commemorated my image in this monumental material. What began as a very earnest attempt at exploring a sort of religious reverence became implicated, through the history of bronze, by ego. In order to reconcile this I decided to commit myself to the indulgence and hand polish the inside of the head to a mirror finish. The bell became a kind of narcissus bowl: a compulsion to rub my image into the surface of the material (rubbing one out, rubbing oneself outwards). Searching for a clear image of myself in the surface of the bowl has become an incredibly laborious but meditative act. The piece might still end up being a bell, but for now I have committed myself to this process where the role of reverence becomes conflated with religious adoration and fetish worship.

NC: Some of your works are centered around the ocean, while others rely on certain properties of magnetism. Can you speak about these twin interests and how they may or may not be related?

JV: I have used magnets in two videos so far, both using magnetic attraction as an illustration/metaphor for the function of desire (as the physics of magnetic attraction mimics the psychoanalytic formula of a pull constituted by a lack). In Seek (2012), a mysterious liquid is pulled forward out of an egg and in Small Pulls (2013) ripples of attractions are created across an imaginary landscape and real body.

In both videos, the magnet is purposely hidden or obstructed by the video’s frame because I like the idea of an unknown attractor; this kind of phantom force that pulls otherwise inanimate materials towards or away from something. I link the sensation of an unknown attractor to the idea of interpellation: a quiet echo of a voice you can only assume is your own that later reveals itself to be a brush with ideological instruction before it signifies itself as such.

Interacting with the ocean feels good; I try not to over think it. Something about its rhythm, unobtainable horizon and unimaginable fullness makes me feel heavy in a very good way.

NC: How important is an element of spectator discomfort in your work?

JV: Visual illusion or trickery is an element that comes up a lot in my work. I like achieving a moment where you are unable to understand what you are seeing at first. This initial (or sometimes prolonged) resisting of signification is something I’m very interested in. It is a moment when signification becomes slippery and unstable. I think it can be very uneasy but simultaneously compelling.

I think the natural reaction to being unable to immediately verbalize what you are seeing forces viewers to search around within their own personal network of associations, making the piece the perfect site for projection of a wider matrix of meaning.

NC: The incorporation of elements that address senses other than the visual is a particularly striking and compelling aspect of your work. Might this be a critical strategy in terms of spectatorship?

JV: Ultimately, it comes back to an uneasiness with and resistance towards language. A different kind of engagement occurs when sense experience is incorporated. It also goes back to the above question in regards to a need for a heavy conceptual/historical understanding of artwork. Viewers become implicated in a way that does not have to be validated by strong theoretical frameworks, but rather relies on their own personal points of departure. For example, I have a participatory performance piece entitled Pulse (2012), where two participants are asked to sit across from each other while I attach contact microphones to their chests. I then amplify the sound of both participants’ heartbeats simultaneously, so that the room is filled with their internal rhythms and heartbeats, aurally mixing until they are unable to tell their heartbeats apart. It becomes an experience and exchange of non-verbal intimacy that challenges the body as a self-contained singular unit in a way that doesn’t require any sort of didactic intrusion.

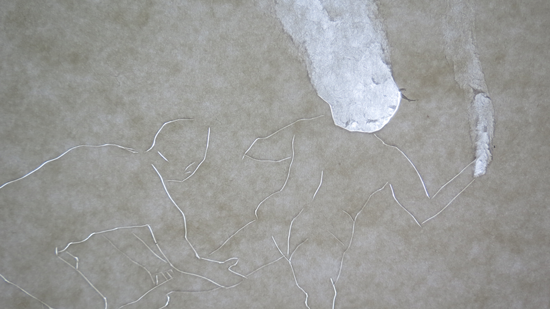

Cut Drawing, 2012, Incised paper.

NC: Another theme that emerges in your work is a sort of violence; your cut drawings are made from incisions and some of your sculptural works (your grandmother’s hands, for example) distill a certain violence of time within them. Can you speak about this?

JV: The Cut Drawings (2012) are interesting to think about in terms of violence. I started thinking about these bodies as transparent scars. It becomes an almost productive kind of violence, where the subject becomes formed by a series of cuts, which have this association with trauma, but it is through this process that these are given lightness and visibility.

The piece with my grandmother’s hands is still very much in its infancy and I am still in the process of considering the implications of using her body (especially as a severed/amputated fragment). But, essentially, the piece will be castings of her hand in beeswax, colored with spices (specifically cinnamon) heated slowly over the course of the exhibition. Over time, as the form of her hand melts away, the nostalgic scents of honey and cinnamon will turn sickly sweet and overly pungent. The disappearance of the object and the scent of burnt spices will infer a kind violence, one that speaks to the bloody history of the spice trade and colonization of Sri Lanka. This would be accessible outside of the art historical cannon, and engaging for viewers without this background. I want to hint at the violence of nostalgia and colonial histories without being obscene or heavy handed. It comes down to this idea of experiencing an element of history rather than just seeing/reading it. Sensory experience is heavily linked to personal history. Playing with a familiar non-verbal history can offer a more productive site of affective engagement than referencing a textual history.

Untitled Castings (Grandmother’s Hands) (studio view), 2014, Foundry Wax and Beeswax.

NC: Because this issue is organized around the theme of ruin, might you be able to speak to any connections that emerge between this theme and your work?

JV: I am interested in art pieces that do not persist—as seen with my bronze head casting. I become very uncomfortable with work that is easily archived, with potential to physically endure time. The idea of impermanence really appeals to me. The process of generating artwork is more important to me than the object itself. It becomes a quasi-political stance to create an object, image or experience that cannot be easily quantified in monetary terms. I guess what I’m really saying is my bank account most heavily identifies with the idea of ruin.

Joshua Vettivelu’s work spans diverse media including sculpture, installation and performance. Their practice seeks to explore how larger frameworks of power impact and manifest within intimate and personal relationships by utilizing the interiority of the body as an unknowable and imagined space. They are currently an instructor at OCADU and have exhibited across Canada and internationally. Exhibitions of note include the British Film Institute’s LGBT Film Festival, Performatorium in Regina, SK, MIX NYC 2013, SUPERNOVA Performance Festival in Washington DC, Dreamworlds in St. John’s, NL and a performance/ installation for ART TORONTO 2012 presented by the South Asian Visual Arts Center (SAVAC). Upcoming exhibitions include M:ST Performance Festival in Calgary.

Natasha Chaykowski is a Montreal-based writer and curator. She has organized numerous exhibitions, discursive programs and arts-based events. Chaykowski held a curatorial assistant position at Art Gallery of Ontario, co-curated the annual Emerging Artist Exhibition at InterAccess in Toronto with Nancy Webb and is the co-recipient of the 2014 Middlebrook Prize for Young Canadian Curators. She was Editorial Assistant for the Journal of Curatorial Studies and the Editorial Resident at Canadian Art Magazine in 2014. Her writing has been published in Carbon Paper, the Art Gallery of York University, esse: arts + opinions, Canadian Art, Gallery 44, and the Journal of Curatorial Studies.