Jaclyn Qua-Hiansen

In a January 2013 interview with the National Gallery of Canada Magazine, Kai Chan says he works with everyday materials like fiber because, unlike traditional fine art materials such as bronze and oil paint, ‘they speak a lot about my life experience, which is more important than creating so called “art” I don’t understand.’[1] Chan is one of the fifteen artists in the Art Gallery of Mississauga exhibition F’d Up! which uses pattern, scale and repetition to radicalize the vocabulary around fiber-based work into a material study.

As a material, fiber is both familiar and intimate — it is something we encounter everyday, and our level of familiarity with it can easily lead to a sense of indifference. We are rarely conscious of having fiber against our skin; our consciousness is raised only by its absence. In F’d Up! contemporary artists use our relationship with fiber to create an entry point of accessibility, only to subvert that very familiarity and present the material anew. Making such an everyday material into something that is unfamiliar is particularly challenging. Artists in this exhibit achieve this primarily through shifts in perspective — the microscopic is magnified and the expansive scaled down; lines, knots and shapes animate material with a sense of the human form; and pattern, repetition and color lull the viewer with a sense of familiarity, only to reveal alternative narratives upon closer inspection.

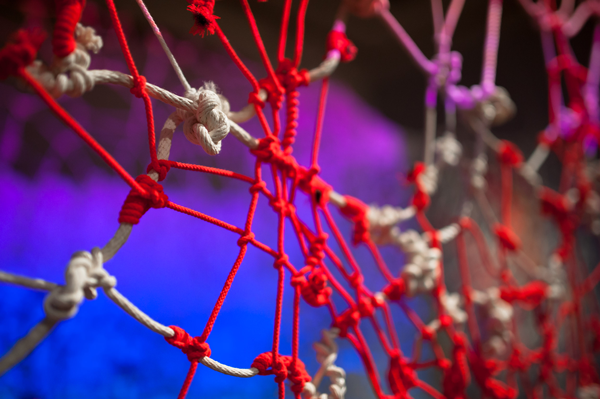

Ed Pien, Corridor (detail), 2010-2012, rope, video projection, drawing, variable dimensions. Photo by Janick Laurent.

In Kai Chan’s Mirage, oscillating patterns of red silk thread suspended by nails in a wall overlap and trail off in mid-air. The overall effect is hypnotic — mirroring and repetition draw the viewer into a state of contemplation. Yet closer inspection reveals the narrative within each strand. The lines overlap yet never tangle, revealing the painstaking care taken to drape each thread over the nail in just the right way. Each strand itself represents hours of labor — from the silkworm spinning its cocoon to the manufacturer weaving the strands into cords thick enough for commercial use. Chan’s choice of material acquires a particular resonance when considering the artist’s place of birth. Historically, the silk trade formed a major part of the Chinese economy, yet the primarily female workforce in the garment factories take a secondary role in history to the men who brokered deals along the silk road. The material’s associations with luxury and happiness also stand in stark contrast to workers’ long hours at the factory, adding a social class element to the gender associations. In a way, the artist’s own care in working with the delicate material is an homage to the care taken by the various individuals throughout history, whose labor has gone unacknowledged, but whose products are infused with an almost otherworldly beauty. Gazing at Mirage from after, one marvels at the grace and fluidity of its lines; focusing on the particular within the piece, however, reveals the grittier reality of how it came to be.

Michelle Forsyth engages with her subject in a similar way. In her series Kevin’s Shirts, she uses the pattern of her husband’s shirts to elevate domesticity into an art form. Pieces of plaid fabric are strewn on the ground, reflecting the clutter of the bedroom. What is commonplace at home is jarring in an art gallery, and one notices the incongruence between the orderliness of the plaid pattern and the careless placement on the ground. Here are pieces of cloth that appear to have been the result of hours of labor — they are clean and, more to the point, they appear handmade. Their thoughtless arrangement therefore appears almost an insult to the care put into them.

Above the pile is a set of four gouache paintings arranged in a square. The work is highly structured; the rigidity of the painted plaid patterns are mirrored in the precise placement of the paintings, plaid squares within white matte squares within wooden square frames all arranged in a square. The eye is drawn by the pattern of repetition, and unlike the repetition in Chan’s piece, there is nothing hypnotic about this. One remains aware of its rigidity, particularly in contrast with the fabric beneath. The paintings are representative of the pieces of cloth, their patterns magnified, flattened and framed as pieces of art. The flattening calls to mind the care that is lacking in the pile on the ground, and references the domestic act of ironing. The arrangement also recalls the care usually taken in folding clothes and putting them away. Forsyth therefore turns the spotlight on the domestic act of caring for clothing, an act done daily yet rarely acknowledged. By using a traditional fine art medium to represent the pattern of an ordinary material, Forsyth seems to demand attention for the fact that caring for the household is itself a work of art, and by using such a personal material as her husband’s shirts, she infuses the installation with warmth, defining this art form as a labor of love.

While Chan and Forsyth focus on the particular, Judith Tinkl pulls back for an expansive view. In Celestial Bodies, she uses upholstery fabric and found buttons to depict the universe. Rather than take the domestic into the public sphere, Tinkl brings the public sphere into the domestic, and thereby argues for an expanded understanding of what really goes on within the home. Her work calls to mind traditional quilting circles; one can imagine a community of women around a living room working on craft projects as they chat. Patriarchal structures have dismissed such chatter as gossip, and traditional perceptions of quilting circles tend to portray women who do crafts together as speaking of nothing but family, food and the home. Tinkl’s work however overturns this convention; the privileging over public discourse rather than ‘hobbyist’ crafting circles is called into question. Each button, a household material, is placed with mathematical precision; despite the do-it-yourself aesthetic, the overall effect is intentional and speaks beyond ‘craft’ and assumptions on the material. Tinkl therefore challenges the gender-biased perception of community craft work — not only can discussions within crafting circles incorporate matters as expansive as the universe, but also more personal matters such as of the home should be accorded similar respect.

Installation shot. From left to right: Kai Chan, What It Is I Came for, I Turn and Turn, Part VI. Claire Ashley, punching bag. Lyn Carter, Bouquet. Lyn Carter, Skirt. Michelle Forsyth, Kevin’s Shirt. Kai Chan, Mirage. Photo by Janick Laurent.

This discourse on gender identity is furthered by artists using structure to explore the human form. Lyn Carter’s Bouquet is a striking study of perspective and pattern. From afar, the piece appears almost flat, a white structure against a bright red wall. A closer look however reveals a large-scale three dimensional sculpture that utterly dominates its corner of the room. Similar to Chan’s Mirage, the work is characterized by graceful repetition. Concentric rings expand and contract around the center, creating a sense of easy fluidity. It stands in stark contrast to Carter’s Dummy, a pink life-size representation of a human form with anatomically accurate Barbie doll proportions. Dummy is as rigid as Bouquet is fluid, and as inert as Bouquet exudes vitality. Unlike the towering Bouquet, Dummy leans against a corner; it is immediately apparent as a three dimensional object, yet it appears flatter, unable to move. In contrast, unconstrained by socially-imposed proportions, Bouquet strains at its edges; striations emanating from the center enhance the sense of scale, and tension in the edges gripping the structure beneath hint at an ever present movement toward release. Bouquet is subtly sensual, female sexuality barely constrained.

At the opposite end of the gallery is Ed Pien’s Corridor. Where Carter’s works have a feminine sensibility, Pien’s installation is aggressively masculine. Just as Bouquet uses feminine contours to challenge notions of femininity, Corridor engages with the discussion of masculinity, combining tenderness and power, bondage and release, and inviting the viewer to engage. The work spans the gallery space, a dominating structure of rough rope. Sadomasochism knots form the web, elaborate structures that are merest points in the pattern. The knots reference an aggressive form of sexuality, providing release by imposing bondage. Visitors are enmesh themselves as it were in the work and allow their perception to be dominated by rough hewn fiber. Yet even within this, the concept of masculinity is explored in interesting ways. The structure holds a sense of subtle beauty and tenderness. There’s a grace within the thick criss crossing lines, and a lovely sheen of color washing over the structure. A video projection reveals shadowy figures crossing past at various intervals, conveying a sense of intimacy, connection, possibly even love.

Claire Ashley eschews form altogether. ‘another tasteless hunk’ is a blob of indeterminate shape. It could be anything from an amoeba to a psychedelic pound of flesh, an unknown particle blown larger than life. Its languor contrasts sharply with Corridor’s tension, and one wonders if this is a furthering of the conversation begun by Carter’s Dummy and Bouquet. If so, the ‘hunk’ in the title, also a gender-based term that objectifies masculinity, may be somewhat ironic. Beyond the socially imposed structure of Dummy and the strained constraint of Bouquet, ‘another tasteless hunk’ is allowed to spread. It is significant that this piece practically pulses with vitality, at rest on the ground but far from inert, free from structure but still far from chaotic. However, being without recognizable form, this piece perhaps eschews gendered connotation as well. Here is corporeality writ large, and defiantly undefinable.

Installation shot. Left to right: Ed Pien, Corridor. Frog in Hand, Wall. Claire Ashley, ‘another tasteless hunk’. Photo by Janick Laurent.

Throughout the exhibition, lines, contours and details examine personal and social narratives, and contemporary artists offer alternative views. It may be the particular within many of these works that conveys stories, yet it is the combination of all of them that take the conversation to a new level. Emblematic of this exhibition’s effect are two of the works: Anne Wilson’s Errant Behaviors and Amanda Browder’s Future Phenomena. In Wilson’s video installation, animated bits of thread traipse and tumble across a screen, creating a snarl that grows ever larger and more agitated. Each thread’s tale in subsumed into a dynamic, intriguing whole. In Browder’s work, a piece of cloth composed of hundreds of patches of donated cloth flows from the ceiling onto the gallery floor. The piece was originally installed on a three-story building and being hung in a single story space causes the cloth to pool on the ground in overlapping waves. Each patch, donated by a Brooklyn resident, carries the donor’s narrative within it, yet within the gallery space, these patches cascade upon each other, piece upon piece, story upon story. The viewer’s curiosity is naturally piqued by the potential for narrative, partially concealed, and it is by engaging with this curiosity, by inviting the viewer to look beyond the familiarity of the material, that F’d Up! achieves its aim of sparking discourse.

F’d Up!

September 26 – November 9, 2013, Art Gallery of Mississauga, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada

Curated by Stuart Keeler

[1] Hill, Lizzy. ‘A Conversation with Kai Chan.’ National Gallery of Canada Magazine. National Gallery of Canada, 4 January 2013. Web. 3 November 2013.

Jaclyn Qua-Hiansen is a writer whose work has been published in BlogTO, Canada Arts Connect Magazine and Spirit of the City Mississauga Life Magazine. She graduated with high distinction from the University of Toronto (2009) with an HBA in English. She also graduated with honours from the Ateneo de Manila University, Philippines (2004), with a BA in Management Economics. She writes a book review blog and has taught social media and creative writing workshops for various community organizations. She currently oversees Communications at the Art Gallery of Mississauga.