Jared Butler

For a decade, Jonathan Field has recreated media images in a body of work entitled Maxwell’s Demon. Making massive, spectral copies by inserting steel pins into black velvet or neoprene rubber grounds, Field has developed a critique of media saturation, interventionist military policy, and economic inequality in the United States at the turn of the twenty-first century. His elegiac replicas, constellations of reflected light, trace the degradation of images. Thus examining entropy, or the systemic tendency toward disorder, the series generates new content: it opens a subtextual discourse by breaking down selected images of the early twenty-first century’s visual culture.

Composed of thirty-four works to date, Field’s Maxwell’s Demon appropriates internet-acquired images from such sources as newspapers, fashion advertisements, and oil paintings hung in the oval office.[1] The British-American artist, based in Savannah, GA, affixes an enlarged, printed copy of the selected image onto a black neoprene rubber or velvet support, and reproduces it by inserting stainless steel straight pins at varying densities, achieving an impressive degree of tonal gradation. Punctures ultimately destroy, and replace, the printed copy. The result is a ghostly after-image, suggesting the elegiac, at an immersive scale.

The project began in 2003, when Field initially pressed his steel pins into sheets of rubber on board. His choice of the petroleum product as support was a comment on the Iraq War and the reality to which the conflict points: America’s economy of consumption fueled by the depletion of global natural resources and sustained through America’s hegemony over oil-rich sovereign nation-states. The tandem series New York Times 2003 and Independent 2003 take images from the major American and British newspapers as the conflict began and escalated, reproducing a front-page photograph from each newspaper for each month of the year 2003. Each group’s twelve images construct a history of American and British hegemonies, the two most potent western powers, at the turn of the twenty-first century. Field, then, reinvents the role of the history painter that has gradually been effaced by advanced recording technologies and constant television news coverage. Where the history painter and the writer of history self-consciously translate information into knowledge, popular news commentators, wan and with countenances long-ago coerced into neutrality, report uncritical and unreflective recorded data to television viewers.

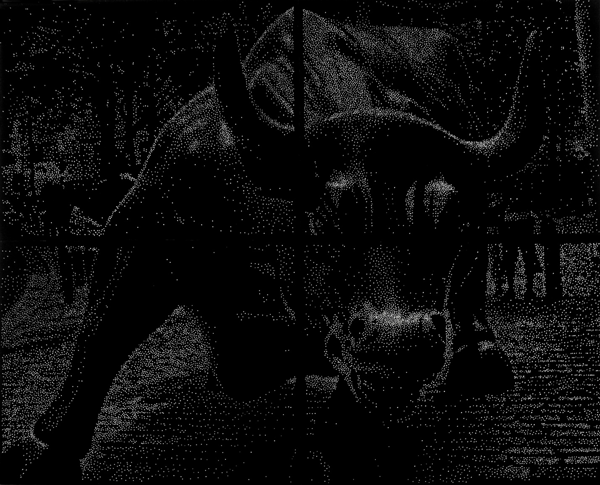

Complex threads of social currency and association haunt the appropriated images. For example, Bull (2009) recreates an internet-appropriated frontal view of Charging Bull, Arturo Di Modica’s 1989 oversized bronze sculpture of a bull frozen in motion, readying itself for a charge (Fig. 1).[2] The work references a bull market, a market trend in which investment prices rise faster than historical averages, prompting increased investor confidence. Di Modica originally placed the bull outside the New York Stock Exchange on 15 December 1989, intending it to signify American resilience and financial power in the wake of the 1987 stock market crash. When financial crisis crippled the American economy in 2008, the bull’s energy and unpredictability, formerly associated with aggressive prosperity, became the symbol of an unrestricted, self-destructive market. To that end, in July 2011, the Vancouver-based anti-consumerist magazine Adbusters released an image of a ballerina gracefully perched atop the bull, which commentators later interpreted as signaling the dawn of the Occupy Wall Street movement.[3]

Jonathan Field, Bull, 2009. Steel pins on black velvet, 94 x 74 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.

Field’s image masterfully renders the bronze sculpture’s dynamism. Its velvet ground absorbs light more efficiently than rubber, generating an impressive contrast between the steel pinheads and the black substrate. Soft and lavish, the high-quality velvet carries feminine associations, which the pins reinforce, evocative as they are of sewing or embroidery. Juxtaposition between those feminine materials and masculine subject matter recurs in several Maxwell’s Demon works but, as a male animal and a sign of power, the bull connotes a hyper-machismo that intensifies the comparison. At 94 by 74 inches, standard dimensions of Field’s pin compositions, Bull divides into four panels of equal size, which are bolted together when exhibited. Registering the decay of the bull as a sign of American optimism and its redeployment as an emblem of Wall Street’s intolerable volatility, Bull exemplifies its maker’s strategy of appropriating media images to create critical works of art.

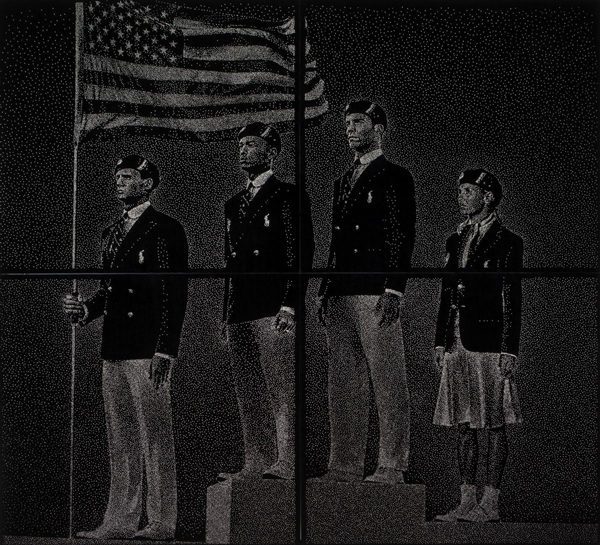

Field’s work since 2012 has shifted from overt political commentary to an interrogation of popular media images. In November 2012, he completed Flagbearers, a reproduced image of four Olympic athletes standing proudly upon a white medal podium brandishing the American flag (Fig. 2). The leftmost figure, swimmer Ryan Lochte, wields the flagpole, decathlete Bryan Clay and rower Giuseppe Lanzone stand upon the podium’s highest tier, and soccer defender Heather Mitts takers her place on the silver medal tier at right. Ralph Lauren Corporation released the original photograph on 10 July 2012, unveiling its design for the American opening ceremony uniform at the 2012 London Olympics (Fig. 17). Inspired by Navy uniforms, the design incorporates Ralph Lauren’s preppie, classic Americana aesthetic.

Jonathan Field, Flagbearers, 2012. Steel pins on black velvet, 90 x 82 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.

In the days after releasing the product image, Ralph Lauren came under fire for manufacturing the uniforms in China. By 16 June 2012, Senator Robert Menendez (D-NJ) and eleven cosponsors introduced the Team USA Made in America Act of 2012; the next day, Representative Daniel Lipinski (D-IL) and two cosponsors introduced the American Clothing for American Olympians Act to the House of Representatives.[4] Aside from public outrage over their production overseas, the uniforms’ design caught additional flak for their obvious militaristic references.[5] Together, the controversies over the uniform’s manufacture and design revealed much about the status of patriotism, globalized means of production, and aestheticized militarism in the American public psyche. Specifically, the uniform debates demonstrated that American policy makers are quick to cash in on the political capital garnered from reinforcing the reading of US and China economic relations as competitive rather than collaborative. Additionally, they indicated the degree to which the Olympic Games, or at least their televisual representations, function to brand, market, and profit from national and corporate identities, rather than as opportunities for international competitive excellence.

The public persona of Ryan Lochte, the most recognizable of the uniform models, lends further interest to the image Field selected for reproduction.[6] During the London games, Lochte could be seen sporting fluorescent clothing and accessories, custom-made sneakers with his name on the soles, and diamond-studded US flag grills. The eleven-time Olympic medalist explained his unique style in a video produced by Speedo, one of his sponsors: “[all] the stuff that I do, like, the crazy shoes I wear—like the grills I wear on the podium, the crazy shoes, all that crazy stuff—like, rock star.”[7] Endorsement deals with Speedo, Mutual of Omaha, Gillette, Gatorade, Proctor and Gamble, Ralph Lauren, Nissan, and AT&T earned Lochte a reported $2.3 million in 2011 – 12, and in June 2012 he became the fourth male to grace the cover of Vogue. After trademarking the phrase “jeah” in August 2012, Lochte began filming the six-episode reality television series, “What Would Ryan Lochte Do?,” which premiered on the cable network E! in April 2013.

No longer the mere world record-setting athlete he once was, Lochte has become archetypical of style choices designed to fabricate a marketable public identity. Clad in commodity images, he intensifies the tension present in the Ralph Lauren advertising photograph between branding and the labor of sport at the highest level of competition. On the one hand, the four athletes are models of dedication, tenacity, and endurance. On the other, they model a hackneyed, militarized conception of the United States stamped with massive and garish Polo Ralph Lauren insignias. Field’s reproduction employs this tension to consider the effects of hyper-commodification on the reality of sport: does athletic excellence function as a means of achieving fame and multi-million dollar endorsement deals? Do the spectacles of the Opening and Closing Ceremonies detract from the real labor of over 10,000 mostly anonymous athletes? What about those ten Olympians or so whom popular media deem beautiful, inspirational, or tragic enough to warrant constant coverage? Do glitter shoes and diamond mouthwear outshine lifelong, laborious training?

Unlike the flat, instantly produced mass images that flood our visual world, Field’s handmade copies take months to produce, and his medium translates that effort, evoking a protracted sense of time. A newfound patience permits us to carefully read the image between the lines, or between the pins, accessing subtext otherwise lost. Weaving these subtextual discourses into a consistent body of work, Field registers a network of political, economic, and social realities in a critical history of the twenty-first century’s first decade. He has developed a medium, defining its logic of organizing and working through information. Increasing layers of subtext and steel pins mark out an interstitial space where the fragmented components of Field’s subject matter enter into discourse with the viewer. Executed during an era of information saturation and an attendant loss of understanding, Maxwell’s Demon provokes reflection, resisting the flatness of the contemporary imagination.

[1] The title Maxwell’s Demon is based on Scottish physicist James Clerk Maxwell’s 1867 thought experiment on how to violate the Second Law of Thermodynamics, which states that all set systems tend toward entropic equilibrium (entropy cannot decrease in an isolated system). Maxwell sought to show that the law merely has a statistical certainty. See Leff, Harvey S. and Rex, Andrew F., eds, Maxwell’s Demon: Entropy, Information, Computing (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1990). Thomas Pynchon took up this idea of a counter-entropy device in The Crying of Lot 49 (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Company, 1965). Pynchon was a focus of Field’s doctoral studies in American Literature at the University of Lancaster, England.

[2] Photographing the bull from this point of view is all but an obligatory tourist ritual; a clichéd image, an internet search result in hundreds of virtually identical images of the bull. One of these images was Field’s source for Bull.

[3] Beeston, Laura. “The Ballerina and the Bull.” The Link. 11 October 2011, url = http://thelinknewspaper.ca/article/ 1951 (accessed 8 April 2013). Adbusters promoted this article on their website after December 2011 (http://www.adbusters.org/content/ballerina-and-bull). The Occupy Wall Street movement was the topic of the issue Adbusters 97 (September/October 2011).

[4] See Team USA Made in America Act of 2012, S.3387, 112th Congress (2011 – 2012), http://thomas.loc.gov/cgi-bin/bdquery/z?d112:s.3387: (accessed 3 April 2013); American Clothing for American Olympians Act, H.R. 6132, 112th Congress (2011 – 2012), http://thomas.loc.gov/cgi-bin/bdquery/z?d112:HR06132: (accessed 3 April 2013). Both bills remain in committee at time of writing.

[5] Achter, Paul. “Is Team USA’s militaristic uniform a problem?” CNN. 28 July 2012, url = http://www.cnn.com/2012/07/27/opinion/achter-olympic-uniforms (accessed 3 April 2013).

[6] Although, it should be noted, Field was not aware who Lochte was when he began making the work.

[7] Riechers, Angela. “What’s the Deal with Ryan Lochte’s Hip-Hop Tropical Frat-Boy Wardrobe?” The Atlantic. 1 August 2012, url = http://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2012/08/whats-the-deal-with-ryan-lochtes-hip-hop-tropical-frat-boy-wardrobe/260618/ (accessed 3 April 2013).

Jared Butler is a writer and critic based in Atlanta, GA. He holds a master’s in art history from the Savannah College of Art and Design, where he was the 2012 Larry W. Forrest Scholar in Art History.