Karen Tauches

All works by and courtesy of the artist.

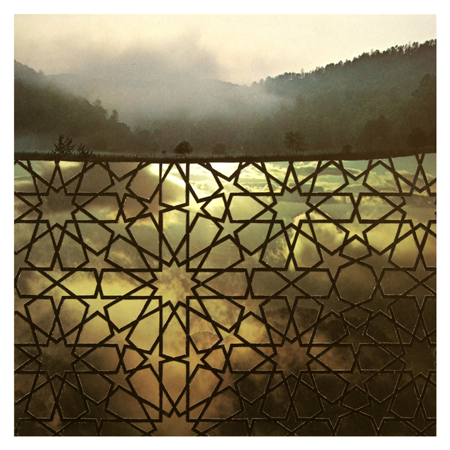

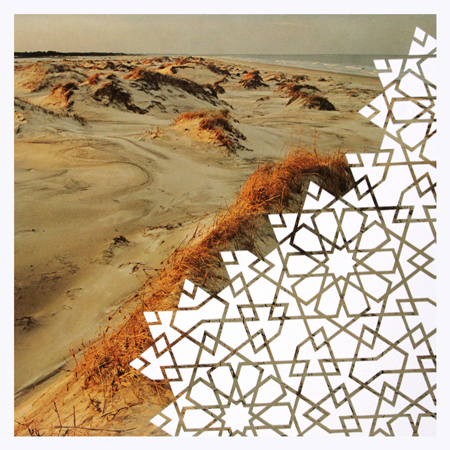

Theory of Slow Growth, 2013, 16 x 24 inches.

Karen Tauches: The title of your latest body of work, “Theories of Everything,” kind of says it all…I am curious as to which came first: the idea or the artwork?

Dayna Thacker: The idea and the artwork developed together, but I found the title for the series a little later. The idea for the series came out of a personal desire to believe in an enduring universe. I was and am disturbed by the ongoing reports of damage we humans are doing to our planet, and I needed soothing. I’ve worked with Islamic sacred geometry intermittently for years, though it’s never been quite so prominent as in this series, and I found myself thinking about these beautiful, meaningful patterns.

Elements of the patterns originally came from Greek, Roman and Arab sources, but the Muslim artists used very advanced and complex geometry to unite and expand them into an all-encompassing system of symbolism. Symbolism isn’t even the right word…these patterns aren’t symbols of other things, exactly. According to the Muslim artists of old, the harmonies and proportions achieved in these patterns ARE the relationships and ratios that make up the universe. They can be applied to planets, stars, the human body, a tree, worms in the soil – everything. They are tracing the pathways of energy from the creative source of Allah, through the process of physical manifestation and back again to the original source. Everything in the universe follows one of these paths. In addition to the physical world, the soul and human consciousness are also manifestations of the creative energy, so the patterns can also be used as meditation aids. They encourage the mind to concentrate on the pathways of creative energy and follow them back to the source. This is a simplistic summary, of course, but it’s got the essentials.

Simultaneously, I had been reading occasional articles about string theory. I recognized a similarity in the description of the strings of string theory and the pathways of Islamic sacred geometry. I purchased Brian Greene’s book, The Elegant Universe, and began to learn about string theory more in depth. Greene makes reference to theoretical physicists’ desire to find the unified Theory of Everything, a sort of Holy Grail theory for physics that will smoothly explain the workings of the entire universe. String theory is one proposed Theory of Everything, but there are many other competing theories. I took the liberty of making the plural “Theories of Everything,” and for my purposes included Islamic sacred geometry as one of those theories.

Theory of Fertile Ground, 2013, 8 x 8 inches.

String theory came about in an effort to unify two other theories: special relativity, which deals with objects and spaces on a cosmic scale; and quantum theory, which pertains to the microscopic world. The result is the poetic idea that all matter is the result of the resonances of vibrating microscopic loops (dubbed strings). Each resonance travels through several hidden spatial dimensions to produce the physical signature of an elemental particle, and those particles work together to create everything in the universe.

The sacred geometric art of Islam is in many ways an ancient version of string theory and the search for a unified theory. To quote Keith Critchlow in his book Islamic Patterns: An Analytical and Cosmological Approach, “The overriding principle…is the unity of existence and therefore the universe. This unity has always an inner and an outer aspect – a hidden as well as an outer way of studying cosmology. The outer embraces sensible observation, the inner is appreciating the expression of cosmological laws within one’s own structure. The goal of spiritual disciplines is to unite the inner and outer, the greater and smaller, into an inseparable integrity.”

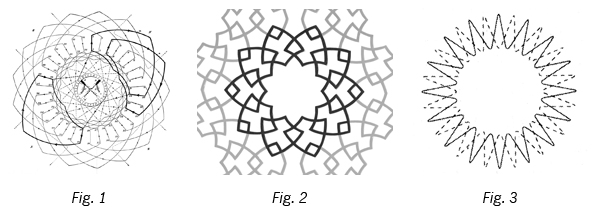

Much like the diagram of a motor’s electrical generator traces the path of electricity as it courses along its copper coil (Fig. 1), the Islamic patterns (Fig. 2) are diagrams of energy trajectories in their route from the Origin to spiritual and physical manifestations, and back again. Similarly, the strings in string theory generate the creative energy of all matter through their vibrational journeys (Fig. 3).

KT: Although that is an inspiring and also complex explanation, I believe your title can also stand as a general statement or declaration. Viewers need not be uninitiated in the science of matter. So, congratulations! This artwork communicates a grand idea without being annoyingly didactic, wordy or dry (as artwork that illustrates philosophy or science often can be). The imagery, process of making and ultimate physicality creates a certain transcendentalism without having to know anything more. Was this purposeful on your part?

DT: I do strive for that quality in my work, although I’m not always successful. My hope is that my work will allow viewers to intuitively grasp the essence of it without having to research, in this particular instance, sacred geometry and string theory. I’m not sure I would call it purposeful…that implies I might have a formula for transcendentalism, which I don’t. In this case, however, I’m standing on the shoulders of giants: as I mentioned, the patterns were/are used as meditation aids and the perfection of their geometry encourages a state of mind receptive to intuition. The type of imagery I choose and the fact that I hand cut the patterns are other ingredients to an accidental recipe that produced a much-desired mental umami – at least for some viewers.

KT: Ever read any science fiction by Stanislaw Lem? He has a character who humorously works on “a general theory of everything.” (Solaris, The Star Diaries, The Futurological Congress)?

DT: I love reading about science, particularly theoretical physics, and I also like science fiction, but I’ve never read Stanislaw Lem.

KT: Use of collage and paper has been an integral element of your studio practice. I can imagine you have a lot of scissors, magazines and books laying around your space! How did you end up working with paper and appropriated imagery?

DT: I work only with books and x-acto knives, but yes, my studio is covered with them. My studio practice began with found objects and papers. For many years I made assemblages – and sometimes still do. Collage was a natural outgrowth of that. I enjoy the natural parameters set by using found objects and appropriated imagery, and I like the transformation of them into something very different.

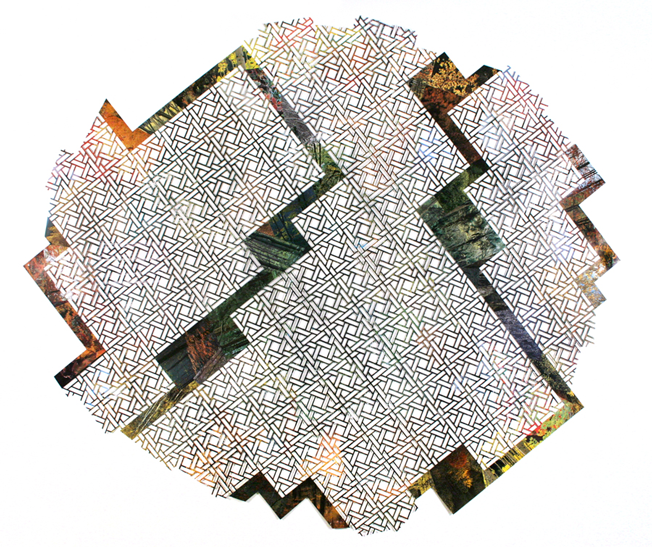

Rising yet Falling, 2013, 27 x 126 inches.

KT: It seemed to me that this body of work broke visually and stylistically from previous ones. “Theories of Everything,” uses bold bright color clippings of nature photography from 1960s and 1970s where as other work seems more like the beige and brown printed matter from the 1920s and 1940s. In some cases, you have freed yourself from the frames, mounting larger works directly to the wall. The holes in the paper just float freely off the wall, illustrating the idea with a kind of conceptual elegance. How did this shift occur?

DT: My previous series is conceptually very much in keeping with my current work. In general, my interest lies in the methods we use to understand ourselves and the world. I particularly enjoy the overlap of the intuitive and logical, and the contemplative and scientific. My last series, Structure of Accumulation,* was based on the idea of using a three-dimensional Buddhist mandala as a modern psychological portrait. The portrait-structures exist in a spiritual space of manipulated perspective similar to that of medieval religious paintings in order to reinforce a quality of symbolic space. Both bodies of work explore visual meditation aids, underlying mystical structures, and varying degrees of scientific thought.

The visual difference between the two series is an evolution of style to better support the new ideas. Also, although it’s been a few years, I’ve made other work that floats on the wall unframed, so using that method in this work isn’t truly a break from my past, but rather a revisiting of previous themes.

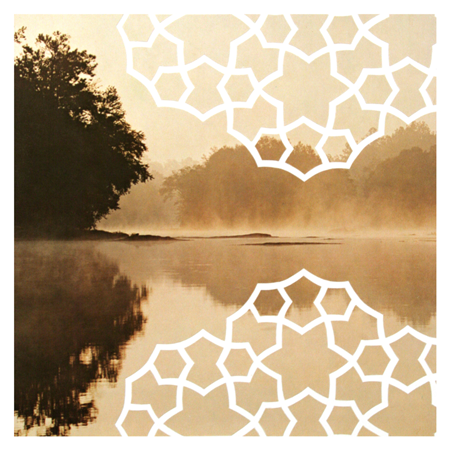

Theory of a Distant Echo, 2013, 8 x 8 inches.

KT: The 1970s especially express an idealism around the love of the Earth and natural things. Is this what drew you to this material?

DT: I personally have a love of natural things, and that’s partly what drew me to these ideas. I don’t equate it with a particular decade.

KT: I especially covet the wall pieces, some of which are quite large and delicate. The largest one, Swift and Tilting, is 78″ x 90,” and has hundreds of exacting cuts, making it look like a piece of futuristic lace. That must have taken you forever! How long does a piece like this take? I understand that in order to transport Swift and Tilting to the gallery, you actually cut it in two. . .please explain.

DT: That piece took approximately a month. In anticipation of moving the piece I chose to leave it in two pieces, then I glued the final seam in the gallery. I hadn’t seen it on the wall until it was hung for the show. I work on the floor to make the big pieces, so I stand on a table periodically to gain some perspective of the piece as a whole.

Swift and Tilting, 2013, 78 x 90 inches.

KT: Like the back of an embroidery, I bet the backs of these pieces are also very interesting. Would you ever consider displaying these as two-sided objects?

DT: Probably not; I don’t really find the backs intriguing. I am considering creating work specifically to hang in space, because I’m interested in how the patterns create and divide space, and I like the parallel idea of the patterns somehow imitating the route strings take through other dimensions.

KT: You now work at Hambidge (a Creative Residency Program, which is situated on 600 acres in the mountains of North Georgia). The founder, Mary Hambidge was quite an advocate of country traditions and spiritualism. Has your time there influenced your work? (I bet you go to a lot of great flea markets!)

DT: I feel sure Hambidge has reinforced some of the themes in my work, if not influenced them outright. For most of my life I’ve lived in places where I had easy access to moderately wild places. Hiking, kayaking, exploring; these were important activities, but I never realized how much they meant to me until I moved to Atlanta six years ago. Working for the Hambidge Center gives me the chance to walk in the woods a couple times a month, and I’ve realized how deeply I need to be connected to wild places. When I’m in the woods my brain feels the same way it does when I look at the patterns of sacred geometry.

Theory of Morning Light, 2012, 8 x 8 inches.

*The Structure of Accumulation series was influenced by several sources, from religious art of the past, to recent scientific discoveries about the mind. The first is the ancient form of Buddhist mandalas, which use simplified floor plans as metaphors for the structure of the human soul. The Structure series proposes that the modern soul would reside in a somewhat less well-proportioned structure than those represented by the mandalas. Supposing our psychological/spiritual selves are formed by what we think – in the way our bodies are composed of what we eat – modern-day souls are made not only of responsibilities shouldered, love shared, curiosities and daydreams, but also of the immense amount of information we absorb, the stress we cope with, the frustration we repress, and our pervasive multi-tasking habits. Existing in a spiritual space of manipulated perspective similar to that of medieval religious paintings, the buildings in the Structure series show that the architectural versions of our modern selves feature some strong basic forms, but there are also dark, disturbing rooms in the basement, stairs that lead nowhere, rickety support structures that could fall at any moment, and odd rooms added to the original building in order to accommodate new ventures. The ‘building materials’ are gathered from the never-ending stream of input we encounter daily, both good and bad.

Working in collage, assemblage and installation, Dayna Thacker uses found materials to investigate thought systems we create in order to make sense of the world and ourselves, with a particular interest in the overlap of contemplative disciplines and scientific theory. A graduate of the University of Tennessee – Knoxville, Thacker has lived and worked in Atlanta since 2006. She was awarded a studio space at the Atlanta Contemporary Art Center for 2008-2013; was a finalist for the Forward Arts Foundation 2010 Emerging Artist Award; and her work was featured in the 2009 Southern issue of New American Paintings. Thacker’s 2010 solo show at the Barbara Archer Gallery was reviewed in the September/October 2010 issue of ART PAPERS magazine; she was named in the December 2012 issue of The Atlantan Magazine as “One to Watch;” and her 2013 solo show was praised in ArtsATL and burnaway. Her work is currently represented by Barbara Archer Gallery in Atlanta and Wally Workman Gallery in Austin, Texas.

As an artist, curator and designer, Karen Tauches produces independently-initiated art projects for historic and found spaces in Atlanta and New Orleans. Her artwork is represented by Barbara Archer Gallery. As a member of the Atlanta art community she participated on many boards including that of Eyedrum, ART PAPERS magazine (editorial board), and Burnaway.org, where she is also a staff art writer and inhouse designer. In 2010, she was an original founding member of { Poem 88 } Gallery and a guest curator in resident at Kiang Gallery from 2011-2012. In 2013 she started a monthly salon program called Sunday Art Salon with Kristin Juarez, which continues on a bimonthly basis to foster local discussion about art and ideas. She works as a designer for the CDC David J. Sencer Museum and is the Gallery Manager for the Forward Arts Foundation’s Swan Coach House Gallery. www.ktauches.com