Steve Locke

I want to avoid the obvious discussion of painting being dead. It’s not. Rather, painting has been killed several times and has been brought back to life by a certain kind of belief, or faith in it. This faith sustains painting as a practice, but recently there has been a kind of representation of the body, the “undead” body in painting that I think has a lot to do with the history of painting, but an attempt to re-inscribe the art in general and body specifically as a site of political agency.

It bears an investigation of the story of Lazarus to get a sense of what I am talking about here. The tale is found in the Gospel of John. Many people focus on Jesus’s act of raising Lazarus from the dead (he had been entombed for four days) as a pre-figuring of his own resurrection. It is that, no question. But there are other elements of the story that I think are often overlooked.

Jesus knew that his beloved Lazarus was dying and arrived at Bethany too late to save him. He does this purposefully. He is addressed by Mary and Martha, who tell him clearly, and with a slight amount of reprimand, that had he come earlier their brother would not have died. Jesus actually cries for Lazarus showing a measure of grief that is not present elsewhere in the Gospels. He then orders the stone to be rolled away and calls his friend from his tomb. The Tanner painting depicts the moment when Lazarus is quickening as the command of his friend.

Henry Ossawa Tanner, Resurrection of Lazarus, 1896, Public Domain.

Photo Courtesy of Wikimedia, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Henry_Ossawa_Tanner,_Resurrection_of_Lazarus.jpg

This story to me is really about faith, a faith that can correct any sort of error. Jesus knew Lazarus was dying and Martha and Mary had faith that Jesus could save him while he was still alive. Jesus actually cries when he meets with the sisters, affirming their grief and his at the loss of Lazarus and affirming their reprimand that this would not have happened if he got there sooner. Martha and Mary accept that they will be together with their brother at the end of their lives, but Jesus reminds him that he IS the Resurrection.

Jesus calling Lazarus forth demonstrates the faith that God can act even when it is too late. So whatever errors we commit, whatever difficulties we face, we cannot assume that we are beyond divine assistance. Lazarus was dead and his sisters had faith that Jesus could heal him, but that was the limit of their faith. The Lazarus tale demonstrates that God’s grace goes far beyond our expectations, and that it can restore even beyond our scope. The lyrics of the spiritual are important here: “He may not come when you want him, but he’s right on time.”

So if the story is about faith as much as it is a “warm up” for the Resurrection of Jesus, how are we to look at paintings of the subject? Tanner, a black man, trained in Philadelphia with Eakins, had to leave the country in order to get the recognition his talent deserved. His Resurrection was painted in 1896, five years after he made France his home. In this light it can be seen as an affirmation of his faith in his talent now that he was in a country that could consider him human. It is also belief that a form or a theme in painting that was well known could be used for new expressive and technical means.

Rembrandt addressed this theme in his paintings of the life of Christ. The best known is the 1630 painting that now lives in the Los Angeles County Museum. The power and confidence of the image of the Christ and the awakening of Lazarus make for a very theatrical image, a true display of stagecraft and painterly hubris. It is a picture by a man who is proving himself.

Rembrandt van Rijn, The Raising of Lazarus, 1630, Public Domain.

Photo Courtesy of Wikimedia, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Rembrandt_-_The_Raising_of_Lazarus_-_WGA19118.jpg

Rembrandt’s first wife, Saskia van Uylenburgh, died in 1642. We have many images of her by his hand, but none as compelling and desperate as her unexpected and luminous presence in The Night Watch of 1642. (V)an Ulyenburgh is painted in golds and ochers and is in a completely different situation of light as if the air around her is filled with charged particles. She is not the subject of the painting, it is actually a portrait of members of the civic guard. What is van Ulyenburgh doing in this situation? She could have been painted as another one of the spectators but Rembrandt uses the divine light of his 1630 Lazarus to surround her.

Rembrandt van Rijn, The Night Watch, 1643, Public Domain.

Photo Courtesy of Wikimedia, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Night_Watch_-_Rembrandt_Harmenszoon_van_Rijn.png

The point here is that she is dead and including her in the painting is a way to keep her alive and vital forever. So there is some measure of faith that he can keep his wife alive through his work, and that she could occupy not just an emotional space, but a civic or public space. It is one of the most heartbreaking images of grief in painting, hidden in plain view, in a public monument.

In addition to understanding faith in painting as a way of raising from the dead (or in Rembrandt’s case, granting immortality) it is also a way of communication between painters and the use of the Lazarus image is common. (V)an Gogh’s 1890 painting looks to Rembrandt’s 1632 etching of the subject. Here the light of the divine presence is replaced by the humid light of St. Remy (and Lazarus is a self-portrait). There is no Jesus in the painting; the figure on the right appears to have an angel’s wing, but it could be a rocky feature of the landscape. So the expression of healing and restoration comes from nature. The divine is embedded in the natural world and God makes his presence known through natural phenomenon. One does not need religion to access the divine in van Gogh’s world, it is all around us. This is marked difference in paintings of this religious theme and marks an important point. If this painting was not made for church, or court, or crown, for whom was it painted? Can it be that this is van Gogh’s affirmation of a new kind of faith separated from the dogma of religion? This in itself is a political as well as a religious declaration, affirming that there is no barrier to the divine and that grace is available to all, without Christ, through the world grace created.

Vincent Van Gogh, The Raising of Lazarus (After Rembrandt, 1890, Public Domain.

Photo Courtesy of Wikimedia, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:WLANL_-_jankie_-_De_opwekking_van_Lazarus_(naar_Rembrandt),_Vincent_van_Gogh_(1890).jpg

In the United States, Halloween is the second most expensive holiday after Christmas. According to the National Retail Federation, Americans spent close $6.9 billion dollars on Halloween in 2011.[1] With spending that large, it is not only children who are dressing up in scary costumes. And the zombie is one of the most popular tropes at this time of year. Whether in movies (from Romero’s Night of the Living Dead to Boyle’s 28 Days Later), television (The Walking Dead), and books (Seth Grahame-Smith’s popular “collaborations” with Jane Austen) the presence of images and ideas about zombies has grown in popular culture. This isn’t the placid return of Lazarus, this is the return of something else, something not quite alive that does not know it is dead or worse yet, something that was hidden or repressed coming back for revenge.

I think there are a couple of reasons for this obsession with the undead. First, I would look to the attacks on the World Trade Center, Pentagon and the hijacking of United flight 93 on 11 September 2011. These horrifying events do not need to be recounted here in detail. I will say that the live news feed had images that will be burned into the minds of people for the rest of their lives. Many of those images were shown on that day and never again. What I will say is that there were many hospitals on alert that day waiting for the wounded evacuated from the towers. There are two things here, the suppression of images of the events and the lack of physical bodies that have us wondering what happened to all of those people. Where are they? We heard about the collection of remains, but it was not something that was seen and after such a conflagration, what could be left? It was as if over 3,000 people suddenly disappeared. As Toni Morrison said there was nothing to be said of these people that could approximate their fate, “no words stronger than the steel that pressed you into itself; no scripture older or more elegant than the ancient atoms you have become.”[2] There was very little presence of the body in the aftermath of 11 September. There was nothing that could be raised.

The second reason is the prohibition of images of the dead returning from our military actions in Iraq and Afghanistan. Former President George W. Bush famously renewed the ban that had been in place since the 1991 Gulf War and forbid images of of flag draped coffins from being taken and circulated, applying this restriction to the families of the fallen as well as the media. Robert Gates, Defense Secretary to the Obama administration began to undo the policy and the President went to Dover Air Force Base to greet a transport of soldiers killed in action. It was the first time in 18 years that we saw an image of a President saluting a flag covered coffin.[3]

To me, these two things are indicative of the body being hidden, repressed or obscured in contemporary culture. And since these two major parts of our history related to conflict and war are repressed, it stands to reason that this is the repression of a politicized body. Since the news is unable (or unwilling) to engage in this discourse on how politics affects the representation of the body, it falls to art to take up this challenge. It has, with varying results.

The American artist Eric Fischl dealt with the experience in Tumbling Woman, a sculpture that was on view at Rockefeller Plaza in New York City in September of 2002. The “controversy” had to do with some people feeling that the work was not appropriate. One viewer said, “It’s not art. … It is very disrupting when you see it.”[4] There were others quoted as supportive of the work and expressed the necessity to some sort of artistic response to the tragedy. The sculpture was removed from the plaza. “We apologize if anyone was upset or offended by the display of this sculpture. It was certainly not our intent. The piece will be removed this evening,” said Suzanne Halpin, spokeswoman for Rockefeller Center.[5]

For his part, Fischl is very clear about his intentions and motivations in making the work. He has often spoken of his relationship to Rodin the connection to the latter’s work visually and thematically evident when one considers Rodin’s Gates of Hell or Burghers of Calais. So like van Gogh, revisiting a theme is a way of communication with another artist. Also important is what Fischl says about the contemporary art’s relationship to the happenings of our time:

Right now we’re shrinking away from truth. No one can criticize the president because we’re in a very vulnerable time, even though he’s doing some things that are terrifying. You can’t express your personal horror and trauma at something that we all experienced. I think that what happened is that since the 60’s there’s been an ambition that art merge itself with pop culture. At first it was an ironic stance, and then it became actually a real thing; people wanted to have art as a playground and as entertainment. And that’s fine in good times, but when something terrible or powerful or meaningful happens, you want an art that speaks to that, that embraces the language that would carry us forward, bring us together, all of that stuff. I think that September 11 showed us that as an art world we weren’t quite qualified to deal with this. Not trained enough to handle it.[6]

Fischl’s point is important: at some point, artists abdicated their ability and responsibility to speak to power, preferring instead to cozy up to power and provide distraction and entertainment. The result of this is while there have been artworks going for enormous prices, the criticality of the artist is questioned and most importantly, art is no longer seen as a site of inquiry or political agency. So what happens when a well established artist like Fischl takes on a major experience in American political life, represents it using the body, and sites it in an area of commerce and public engagement? It can be removed because it may upset or offend. Unlike the Night Watch, this dead cannot be immortalized in public.

Art is no longer expected to provoke, inquire, or analyze. The artist is no longer a political agent, a citizen, a member of a public. S/He is reduced to entertainer, a provider of distractions. Given this situation, Marinetti’s Futurist Manifesto would have been in the “Entertainment” section of Le Figaro instead of the front page.

Like Fischl, Italian artist Maurizio Cattelan’s use of the body in All addresses the repression of the dead. Fabricated from marble and carved to mimic the shrouded body, the work provides a site to mourn and a body over which to grieve, things that were denied in the above cited political events. Its orderly placement recalls the military transports or battlefield hospitals and the whiteness of the marble “fabric” removes ideas of a national identity. These are ALL of the dead, wherever and whenever. Also, Cattelan’s treatment of the material is suggestive of the body without representing it directly, thus evoking a corpse without making one. It is hard to believe that you cannot simply pull up the sheet and see the body. The work is a denial of the closure one obtains by confronting the dead body of a loved one. It calls into question the closures denied by obscuring the body in recent American political life.

Dana Schutz makes paintings known for their powerful color and complex compositional strategies. They are also contemporary exposures, presentations, and investigations of the body as a site for group discovery. Presentation shows a multitude at the burial of a body that seems aware of the viewer, dismembered and not quite dead. The open grave seems to be premature and the legion seems to be waiting their turn to poke, prod and penetrate the body laid out for them. Beyond being indicative of Schutz’s abilities in painting, it is indicative of a populace that need to look at what has happened. How did this body come to be here? Who is responsible? The situation is no one’s fault, but all of the people in the painting are implicated and involved. A truer image of the country’s relationship to war and its effects cannot be found in contemporary art.

In addition, Schutz has the ability to show us the things we know happened but we didn’t get to see. The Autopsy of Michael Jackson was painted before the beloved singer’s death. Jackson’s immortality is assured from his recordings, but what Schutz has done here is render him as so much clay. Far from granting him eternal life in the painting Schutz does what the media circus around the star could not do; she restored his essential humanity. Even the mask of his face, altered by surgery, reveals a peace that he could not attain in life and his clothes, stacked neatly on the table at right, no longer conceal the fragile being that was so dazzling to watch.

Zombies figure prominently in the work of Ben E. Ward. Using his own experience as a white man in the American South and the presence of monumental architecture honoring the Confederate dead, Ward has created a suite of paintings that posit the repressed possibility that “the South shall rise again.” It does rise, but undead and unbidden:

The works presented are a reaction to a memorial erected for the Confederate dead in Savannah Georgia’s Forsyth Park. The monument’s inscription reads, “COME FROM THE FOUR WINDS O BREATH, AND BREATHE INTO THESE SLAIN, THAT THEY MAY LIVE.”I have created several memorial portraits of the aforementioned slain. They are painted as zombies, creatures neither living nor dead. The paintings and drawings are an exploration of issues regarding race culture. As a white male in the South I have been allowed to view racism candidly. This has played an essential role in my reaction to the monument. The zombie memorials exploit the absurd presentation of the original Confederate memorial.[7]

Ward takes the words of the memorial and makes them in horrifying flesh. He asks, “What would happen if the four winds did breathe life into the slain? He then takes this question as a jumping off point for a painterly investigation of the monument and a critical engagement with his own past.

Ben E Ward, Come From The Four Winds (large), 2007, Oil on canvas, Image courtesy the artist

He embues the heroic images of the soldier with the coloration and mannerisms of the undead, showing the effects of a putrefying ideology. He takes the Lazarus myth and recomposes it. Without grace (from God or nature) the reanimation has to rely on the racist structure of Confederate supremacy. Ward shows the effect of politics on the body. He also uses painting to critique a physical political site. He looks at the monument in Forsyth Park as an incitement to act. His paintings are an eloquent and explosive response to his own upbringing and his relationship with public space.

Since the first Gulf War, we have experienced political violence at a remove. We see buildings destroyed and bombings carried out from the control panels of planes and drones, where the marvel of technological achievement mediates our connection to the recipients of this bombs. More than one article has raised the problematics of a relationship between entertainment culture, video games, and war.[8] Barnaby Furnas makes paintings that carry the resonance of video games despite their painterly flourishes. He engages with death and mayhem against the impossible blues of a Pixar-generated sky. The canvas becomes analogous to the screen (which could be posited as the new “window”). Paintings like 2002‘s Hamburger Hill transform one of the bloodiest battles of the Vietnam conflict into the idioms of a role player game. Sprays and splashes of paint reconnect the legacy of Pollock to political context and the titling moves the painting into American history. The slick application and illusion of texture reinforce the televisual. In Furnas’s paintings the body gets blown apart and reassembled; he re-presents mediated political violence, its link to entertainment and because he stops motion, he concentrates on the consequence of violence, and how it politicizes the body.

Tom Burckhardt’s paintings are often humorous and critical of painting itself. In 2008, he made of series of paintings that seemed to be collapsing under the weight their own history and their inability to provide moments of transcendence through abstraction. The works contained painstakingly fabricated objects that were paintings, by which Burckhardt questioned the Modernist rectangle as the singular site for transformation. In works like Homer Paint Bucket (2008), a painting slumps on one of the ubiquitous Home Depot orange buckets, creating a vibrant chromatic conversation.

Tom Burckhardt, Homer Paint Bucket, 2008

The abstract painting seems too weak to develop a relationship an independent relationship to the wall. (In conversation in 2008, Burckhardt said to me, “It’s not that painting is dead, it’s just really tired.”) Burckhardt paints the bucket with a level of verisimilitude that makes it easy to mistake it for the real thing, thus realist painting is holding Modernism up. The paintings bow, sag, and flex as a consequence of some unseen weight. Their animated character, the gestural Modernism, and the realist supports suggest that something has ended, perhaps a collective faith in Modernism and Expressionism. It is no longer possible to be proud and we all need a foundational relationship to reality, however illusionistic it may be.

David Park, an artist committed to figuration in the 50s when such a position seemed retardataire, remarked that “Art ought to be a troublesome thing, and one of my reasons for painting representationally is that this makes for much more troublesome pictures.” [9] The body in painting and the body of painting itself have become always been a site of the impossible and the miraculous, but let us not forget that they are also a site of agency and criticality. In the contemporary moment, it is imperative that we have an art to which we can look for an unvarnished examination of our experience. This means that the entertainment function ascribed to art over that past 3 decades must be discarded and that the artist must resume her/his place as an agent of political discourse.

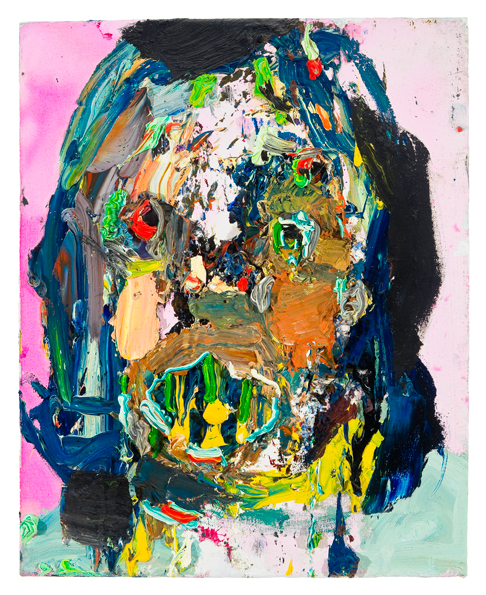

Lastly, the work of Summer Wheat takes on this trope literally head on. In a series of “zombie” paintings, Wheat transforms the material nature of paint into putrefying flesh and exposed bone. The horrifying imagery is exacerbated by the lush color of her thickly impastoed surfaces and her ability to quicken the expression of her portraits through a deft and dramatic rendering of their anatomical features, no matter how rotted they may be. Blood Thirsty Phoebe, contains all the hallmarks of abstract, gestural painting but the marks, smears, and piles of paint continue to resolve themselves into a head with vacant searching eyes with sense of pathos. Zombies are caught between the living and the dead and Wheat, with an amazing sense of portraiture and the macabre, locates her work in between depiction of personage and declaration of paint. Her works is an affirmation that painting will return and return again, each time bearing its accumulated history as a mark of survival.

Summer Wheat, Blood Thirsty Phoebe, Acrylic and oil on canvas, 16”x20”, 2010

The traumatic elimination of the body, through terrorism, war, and political maneuvering is a repression of something we all know is present, even though it is hidden from view. The presence of the zombie, its defiled, dead, and active body, is that repression returned to us. Contemporary painting is uniquely positioned to use this trope, literally and figuratively, to critique and fight against the elimination of the body part of body politic. There are many artists beyond these who have taken up this challenge.

This essay contains ideas that were presented as part of a panel discussion at the Southeastern College Art Conference (SECAC) in Savannah, Georgia. The panel, “Painting in the Collapsed Field,” was moderated by Craig Drennen and included David Humphreys, Wendy White, and Katherine A. Smith

[1] Kathy Grannis, Consumers Eager To Have A Frightfully Good Time This Halloween, According To NRF, http://www.nrf.com/modules.php?name=News&op=viewlive&sp_id=1197 (September 2011)

[2] Toni Morrison, The Dead of September 11 (2001), http://www.legacy-project.org/index.php?page=lit_detail&litID=83

[3] Mail Foreign Service, http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-1223819/Obama-faces-real-cost-Afghanistan-war-salutes-flag-covered-coffin-fallen-soldier-midnight-homecoming.html (October 2009)

[4] Associated Press, Sept. 11 Sculpture Covered Up, http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2002/09/19/national/main522528.shtml (February 2009)

[5] Ibid

[6] interview with Eric Fischl and David Rackoff: Tumbling Woman & Post 9/11 Modernism, http://www.newyorkartworld.com/interviews/fischl-rakoff.html (September 2011)

[8] Jeremy Hsu, For the U.S. Military, Video Games Get Serious, http://www.livescience.com/10022-military-video-games.html (August 2010)

[9] Caroline A. Jones, Bay Area Figurative Art, 1950-1965, (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1989)

Steve Locke was born in Cleveland, Ohio, raised in Detroit, Michigan and lives and works in Boston, Massachusetts. He makes paintings, drawings, books, mail art and installations. He has had exhibitions at The Boston Center For the Arts, The Artists Foundation, and Samsøn in Boston, The Danforth Museum in Framingham, Massachusetts, Aramona Studios in New York and Gallery Peopeo in Beijing. China. He has had exhibitions and solo projects at VOLTA 5 in Basel, Switzerland. He has been awarded grants from the LEF Foundation and the Art Matters Foundation. He is represented by Samsøn Gallery in Boston, Massachusetts, where he will have his second solo exhibition this May, titled “you don’t deserve me.”