Vishwa Shroff with Avantika Bawa

“A line is a dot that went for a walk.” – Paul Klee

In May 2022, Avantika Bawa and Vishwa Shroff went walking in Basel, Switzerland, home of several well-known Brutalist buildings, as well as some more obscure ones, and footnoted everything in between the sites. While Bawa and Shroff both make work informed by their shared love of architecture, and both resist the imposition of narrative, their approaches differ in terms of materials and mediums. Excerpts and thoughts from that conversation constructed this dialogue:

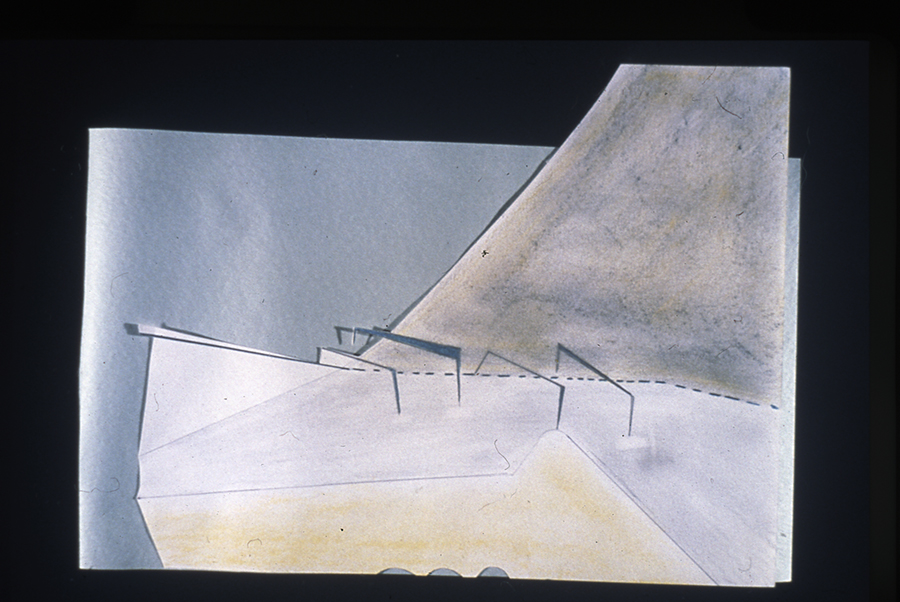

Brunnmatt School (left), Walter Maria Förderer, Rolf G. Otto, Hans Zwimpfer, Basel 1960-1965

Basel College of Art and Design, (right), Switzerland, Baur, Baur, Bräuning, Dürig, 1961

Image courtesy Avantika Bawa

Avantika Bawa: Vishwa, can you start by telling us how you navigate the organic space of nostalgia, and how and why you choose precise visuals such as straight lines and geometric shapes to manifest what you refer to as “contemplation(s) on memory and our relationship with the material world?”

Vishwa Shroff: Robert Hughes, in his essay “The Mechanical Paradise,” discusses this variability of perspective, explaining that “your eye is never still. It flickers, involuntarily restless, from side to side. Nor is your head still in relation to the object; every moment brings a fractional shift in its position, which results in a miniscule difference in aspect.” It is this notion of movement with a given built or architectural space that I am interested in most. I consider my practice observational rather than imaginative, and the drawings attempt to arrest the movement of my body within the spaces that I, sometimes momentarily and always at the mercy of watchmen, occupy.

Once again borrowing Hughes’ words, these observations are “more like a mosaic . . . of multiple relationships, none of them . . . wholly fixed. Any sight is a sum of different glimpses.” The drawings are then a record, each a minor notation of a particular gaze at a particular time that in itself is a momentary pause within a series of fluxes. The spaces that I am recording are intentionally conceived and embedded with mnemonic narratives. Narratives are evocative of lived occurrences, of stories implied within alterations and altercations of a larger historical narrative that transpires as an inexperienced nostalgia derived from archival material and popular culture.

VS: Avantika, I remember with great fondness a presentation you had given at the Faculty of Fine Arts, Baroda sometime around 1999, when you had claimed to have an office job forcing you to think of stationery as medium. I particularly remember a series of works using staple pins that emulated cityscapes. Can you talk a bit about your considerations and interests at that time beyond the material aspect?

AB: Even before my undergraduate years at the Faculty of Fine Arts, of Baroda, India, my focus was on drawing and painting construction sites, derelict or historic buildings, and obsolete machinery using traditional materials such as pastel, gouache and acrylic. When I moved to Chicago in 1998, these materials were easily available, but also pricey and somehow not as exciting. I was instead fascinated by the crisp manufactured aesthetic of materials from office supply and hardware stores. The ability to toy with their functionality by using them only for pure form felt cheeky and satisfying, and the direct access to discarded supplies while working in an office also saved on costs.

Chicago’s grid was a stark contrast to the chaos of the major cities in India where I grew up. I realized that the modularity, with its similarities and repetitions, was worth exploring. It was deceptively simple, but not strictly minimal.

As for the use of staples, it recently dawned on me that the work I do with scaffolds is an extension of that earlier work, but constructed on a larger scale. Both are industrial, hard edged and functional metal forms that I repurpose in my drawings and installations to respond to site, or echo a cityscape. Staples connect pages and scaffolds enable the construction of buildings that grow from plans, and while both serve their intended functions admirably, I’m more interested in looking past their intended uses, manipulating them as elements in their own right.

Avantika Bawa, Staples, graphite and color pencil on paper, 8.5″ x 11″, 1998

Avantika Bawa, #FFFFFF, Painted scaffolds, dimensions variable, 2020, Ditch Projects, Springfield, OR, USA

AB: Coming back to your response, can you talk about how you move from these narratives to a space of abstraction, of an essence? When I see your work, I love the physicality of the mark and the way you work with empty space, but I am more and more intrigued by what I remember of it as well; the after image, the lingering memory. Perhaps I like this experience because it’s more about the form, and the spirit of the original source than the source itself.

VS: Most of the drawings aim to record movement, perhaps that of the eye or the body or both. Tim Ingold quotes Mary Carruthers as saying “ductus insists upon movement, the conduct of a thinking mind on its way through a composition.”[1] This act of emptying or extracting, abstracts towards a visual language that resonates movement. Simultaneously, such paraphrasing of in-situ situations allows a level of detail that mimics them. Recomposing, translating, and playing with linear and axonometric perspective, plans, elevations, and parallel projections, in combination with other drawing methods, almost inevitably leads away from narrative towards recapitulated drawing that may still silently embrace chronicles.

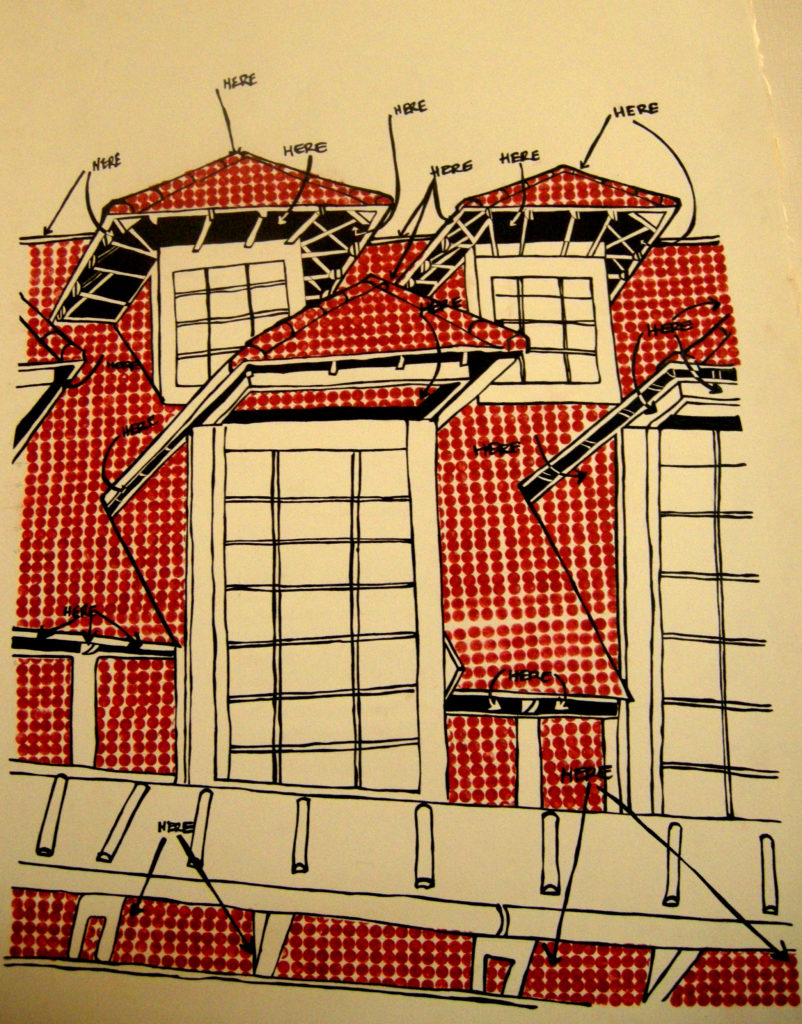

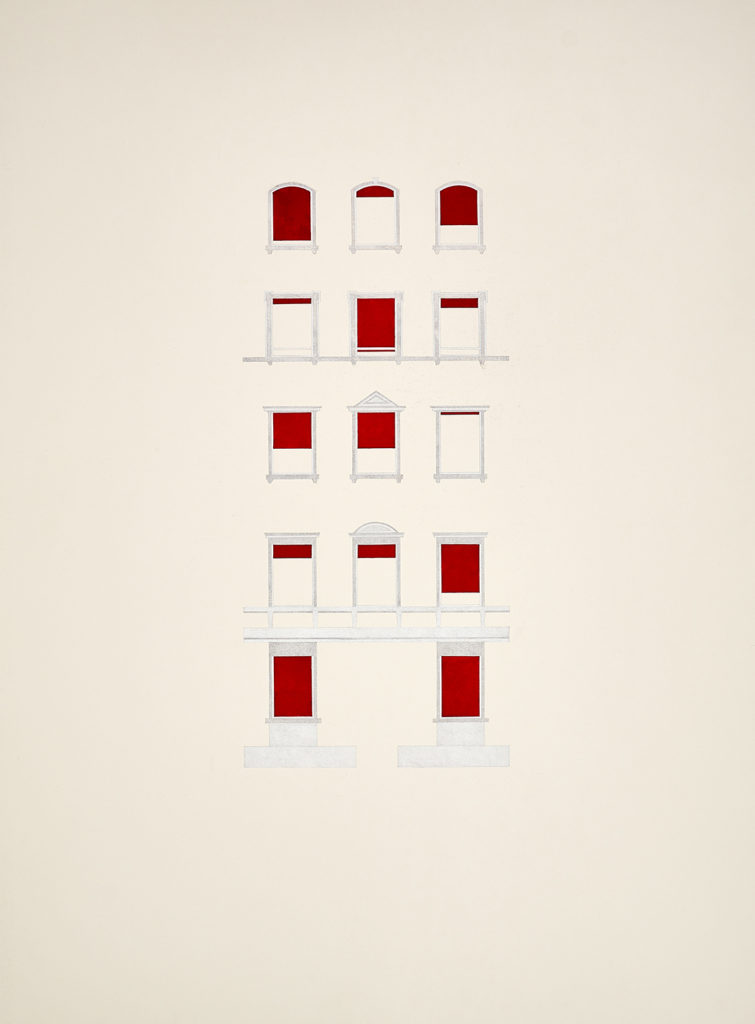

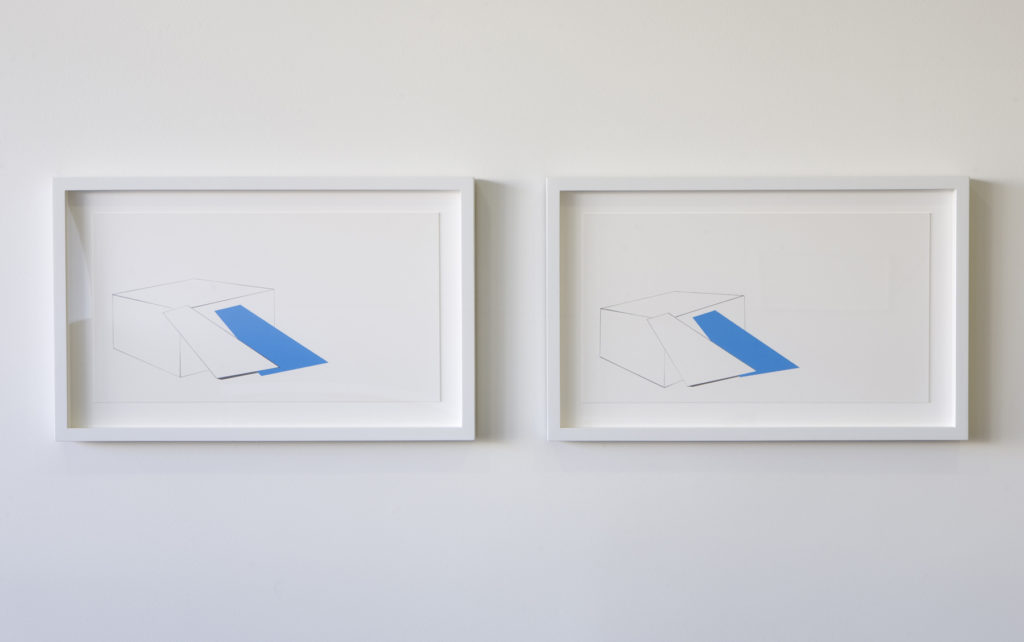

Vishwa Shroff, Here here, (left), ink and rubberstamp on paper, 560 x 380 mm 2010

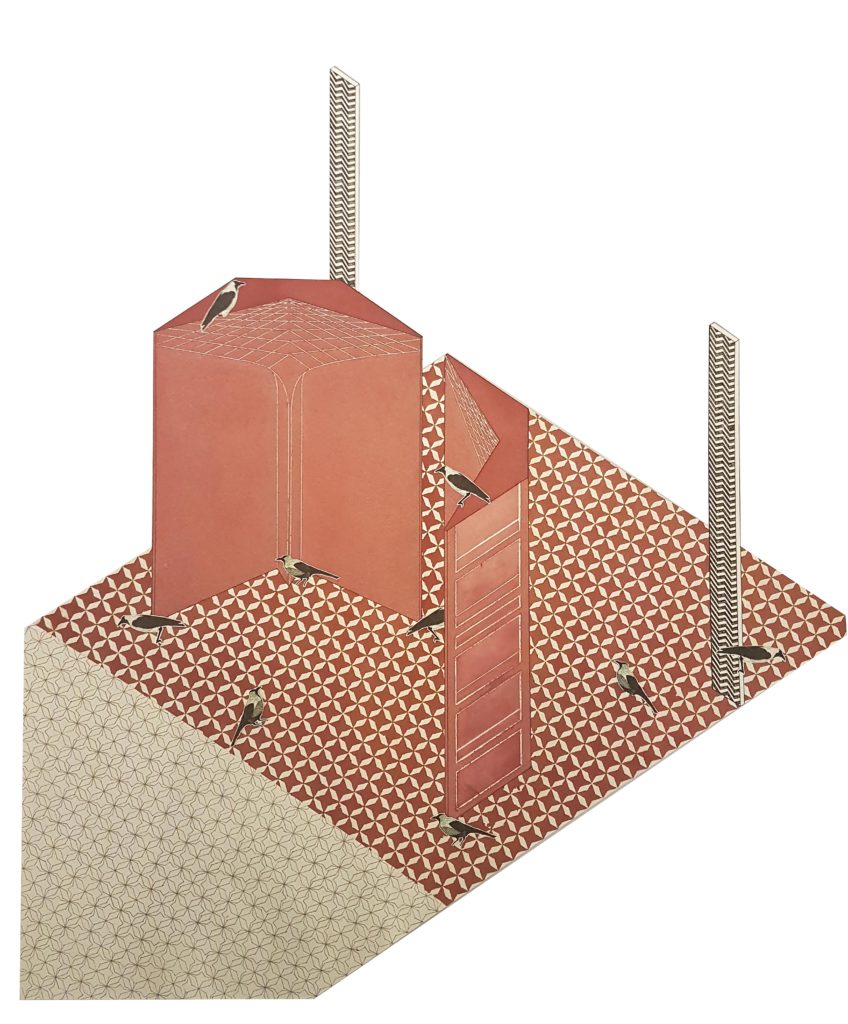

Black Holes in carry sacks , (right) Ink, water color and archival print on paper, 31″ x 22″, 2017

VS: We, you and I, are trained within a narrative tradition, both within the cultural context and as an overriding conceptual basis at the Baroda school. Yet, your work too has distanced itself from that earlier figurative work as well as inclinations towards such narratives. Could you talk a bit about this shift – how you conceptualize the composition and its underlying interest?

AB: Although I was trained in the narrative tradition and enjoyed figure drawing (as a study) as an undergraduate, it was the inanimate, yet raw energy of construction sites, abandoned buildings and dated machinery that drew my interest because of their weathered physicality, unknown pasts, or potential futures. Initially, in response to the weight of that tradition, I projected my own narratives onto these inanimate forms, but over time the projection brought on a sentimentality that took away from the formal rigor of the work. And so I slowly started to walk away from any form of storytelling.

Earlier I talked about how the grid of Chicago informed my work when I moved there from India. I navigated the city physically through walking and biking, and conceptually as I made [obsessive] combinations of straight horizontal and vertical lines in the studio. Allowing myself to get lost was important, as it led to new discoveries and sharpened my ability to observe. My sense of direction is awful, so this happened often, intended or not! As a result, breaking away from structure while still retaining a sense of the hard edge also happened in the studio.

This sensibility of navigating the mechanical with the organic can be seen in my site-specific work. Every installation starts with drawings made on location. I then reference these drawings, in addition to photographs and architectural blueprints of the site, to further develop my ideas. While these provide signposts for the installation, I allow intuition and experimentation to take over once I shift to the space itself, so that the resulting artwork emerges from both meticulous preparation and serendipity.

Avantika Bawa, Mathesis: dub, dub, dub, cardboard boxes, crates, paint, bricks, metal sheets, and video projection, 80′ x 45′ x 20′, 2009

AB: Both our practices require a certain degree of perfection, or at least an image of perfection in how we draw and compose hard-edged forms. How do you approach this perfection, and how does experimentation and failure inform your practice? Do organic and handmade lines (without the support of a straight edge or tool) ever belong in your work?

VS: Oh my! I do not think of the works as perfect or containing perfectly straight edges and lines. In fact, the crispness comes entirely from the process. I have been very interested in graphic printmaking methods, especially serigraphs, where the image is layered, so to speak. Technically, the image is transferred onto the silkscreen and the ink squeezed through it; this creates a hard-edge, no matter how fuzzy the image is, and it places the color with a flatness that I enjoy.

You could of course then ask, why not work in serigraphy? I also enjoy the depth in the drawings that comes from my struggle with emulating such hard-edged flatness in watercolor and ink. I tend to avoid ‘handmade’ lines. I am extremely skeptical of the romanticism attached to the artists’ hand and attempt to find a balance between marks made by hand and those made by mechanical means, keeping the drawings somewhere in-between too. While very fascinated with Ellsworth Kelly, I wanted to find that inter agency that may be permitted by the hand emulating the mechanical.

AB: Your response reminds me of something I said to a friend recently while talking about lines:

A straight line is the sexiest thing ever. A handmade straight line in graphite is sexier still. This blur and interplay between the mechanical and human is one I focus on.

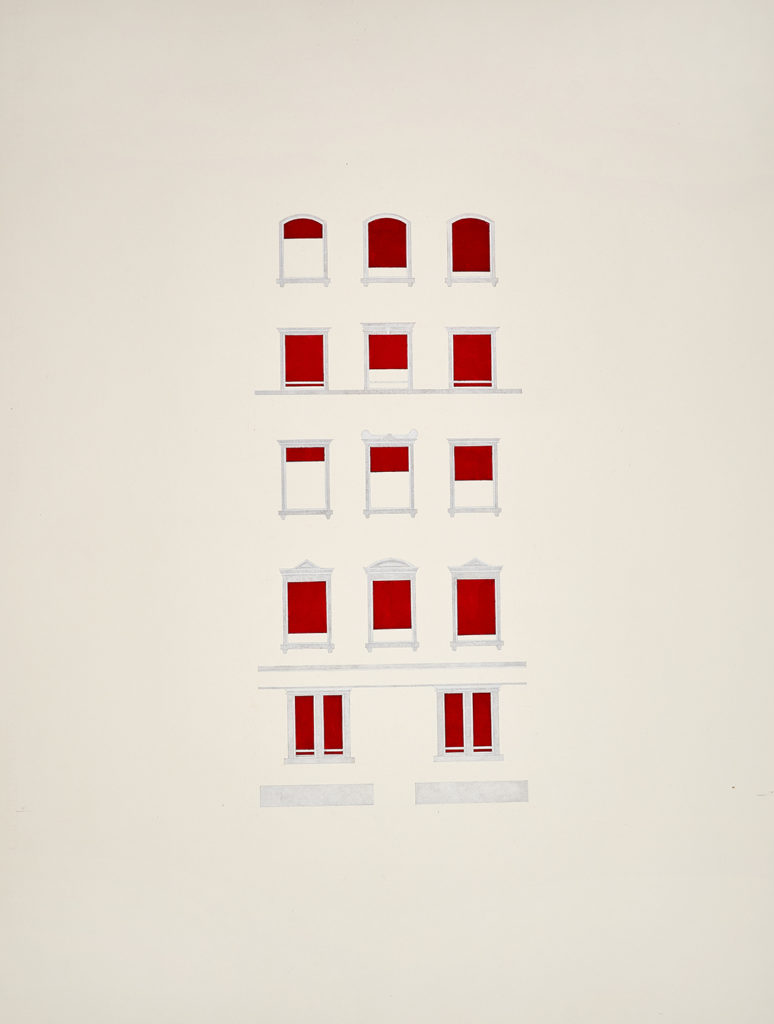

Vishwa Shroff, Apature #1, #2 and #3, silverpoint and ink on paper, 30″ x 22″ each, 2022. Image courtesy artist and TARQ.

VS: These days, it seems that most art finds in its descriptions a political context or more accurately, a politicized and current affairs platform upon which art somehow needs to rest. I find this difficult to get my head around as I would still and perhaps naively hold on to ‘for its own sake’ or the politics of the making processes. Your work too doesn’t address externally charged milieux, but rather questions the act of art-making itself. How do you deal with this ‘requirement’ within your practice?

AB: I could not agree with you more. While I acknowledge art that addresses politics has an important role in the larger picture, that’s not all we need in this ‘larger picture’. Art for ‘art’s sake’ is almost a big no no and I find that odd. If a visual cannot exist without the power of a narrative, then what’s the point?

As an Indo-American female artist, I feel an expectation (from the so called ‘trends’ of the art world) to make work that addresses issues of race, identity, and gender, but this is not the work I feel driven to make. Instead, I focus on a deceptively simple response to site, space, and structure, how differences in site, space, and place affect the ways we experience the same form. I resist the imposition of narrative, as well as the traditional hierarchies of medium and materials.

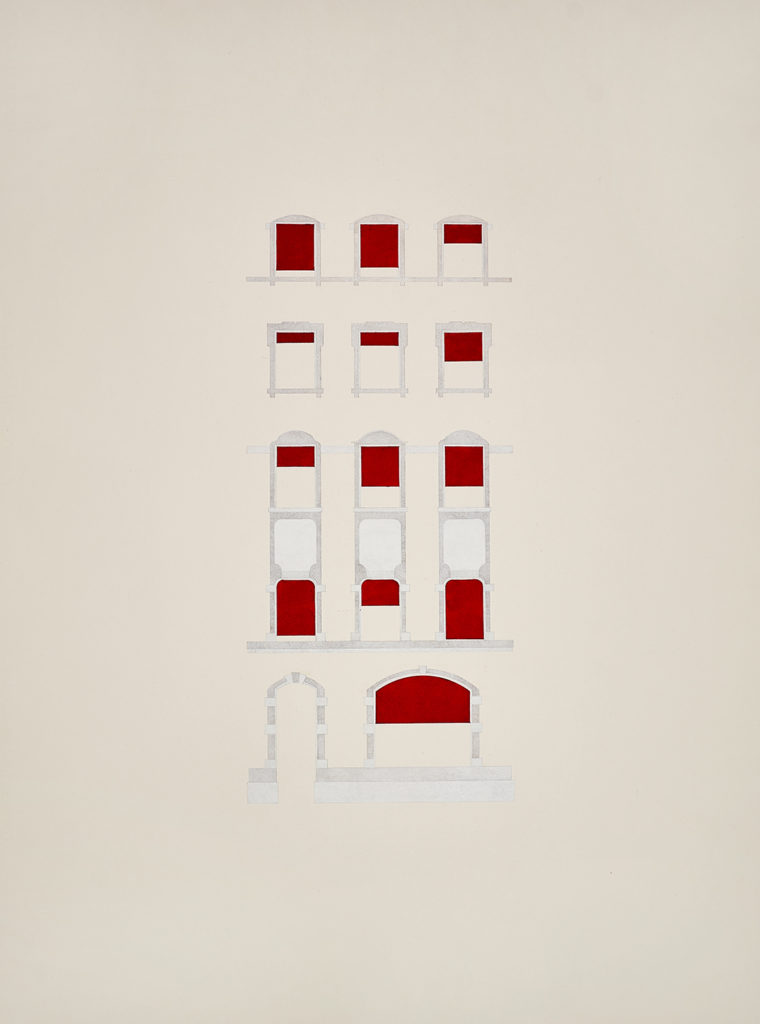

Avantika Bawa, Two Blue Drawings, Perfect Distortions at SALTWORKS, graphite and acrylic on paper, 18″ x 21″, 2008

AB: How do you catalog and document your sketches and process? Is this evolving archive of importance? What does your raw data look like? In the past I was a big believer in the sketchbook, but now I prefer loose sheets of paper, some that I save and most that I eventually destroy. And so my limited archive consists of sketches on larger sheets of newsprint and A4 paper and, when it comes to work related to installations, drawings done on blueprints and photographs of the site. There is something liberating in not holding on to evidence of every step of the process. Plus it’s less clutter! But then I look at the work of DE May and am blown away by his sketches and archives!

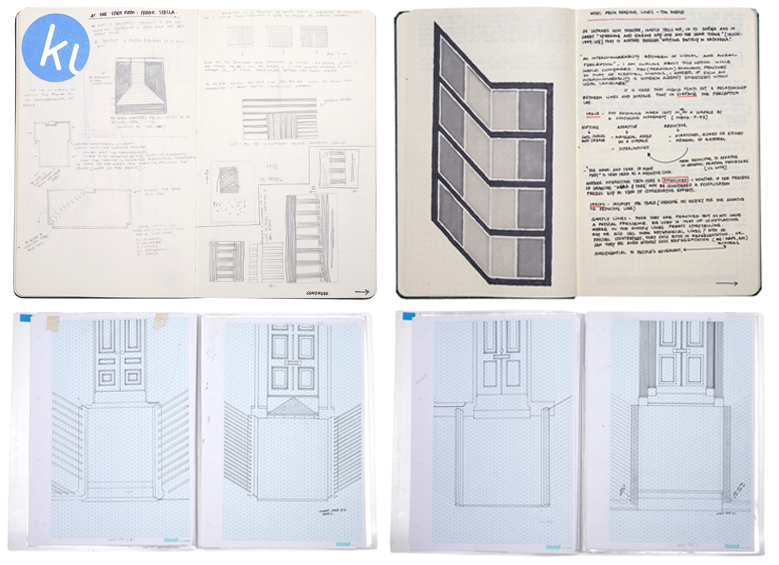

VS: I thoroughly enjoy keeping a sketchbook and think of it as a magical carpet on which I can brood or rant, and record thoughts that come about while reading books or visiting exhibitions or sketching. Their underwhelming format supports my otherwise anxious mind and I refer to them again and again while starting new drawings or projects.

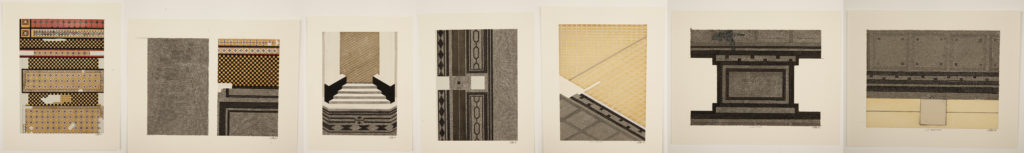

Vishwa Shroff, Transition, watercolor, acrylic medium and ink on paper, 4.5″ x 10.5″, 2016. Image courtesy artist and TARQ.

So, for the last 15 years or so, I have maintained and kept all my sketchbooks. But it is only since 2019, that I started to think about them as archives, and have extended it to drawings and notes made on loose sheets, rejected material tests, graph and axonometric sheets that I use in preparation of the final works, etc.

I think two significant moments compelled me to think of all this material as a record worth leaving behind as reference materials. The first came in 2019 when TARQ gallery invited Deepthi Sashidharan of Eka Archiving services to its annual artist’s weekend to conduct a workshop. The second was in 2020, when I started to rummage through artists Jyoti and Jyotsna Bhatt’s archives. While Deepthi taught us methods of archiving, it is the archives of the Bhatts that have made me think of the various ways in which such material may be used by someone other than me.

Recently too, I had the opportunity to spend time with Donald Judd’s and Frank Stella’s drawings at the Kupferstichkabinett archives of KunstMuseum Basel, where I learnt so much about the thought processes of these artists. I now tend to keep all my drawings, sketches and notes in files and folders and have even started to make a record of books, films, music and other such media that influence my practice. I have loved retrospective exhibitions, and now that you ask, I may be subconsciously preparing for one!

Vishwa Shroff, Sketchbook Pages, 2022. Image courtesy artist and TARQ

AB: “Are there buildings you like to visit over and over again?

VS: Le Corbusier’s Villa Sarabhai in Ahmedabad and The Barbican Estate in London are two sites that come to mind immediately. With both, it is the domestic arrangements that I am interested in. But what fascinates me most is not individual buildings as much as a stroll around the city from where I am able to extract elements from buildings.

What about you?

The Barbican Estate, Chamberlin, Powell and Bon Architects, London, England. (built 1984). Image Wiki Commons

AB: The Jantar Mantar and Quatba Minar are two structures I almost always visit when I go home to New Delhi. On each trip, I experience the buildings in a new way and with a different sense of why and how they exist. With their striking combinations of geometric forms at large scale, these structures have captivated the attention of architects, artists, and art historians worldwide, yet remain largely unknown to the general public.

Jantar Mantar (jantarmantar.org) is an observatory located in the heart of the capital (New Delhi) and was built in 1724. Its bold and functional structure draws me in and I‘m fascinated with the time period in which it was built. The Quatab (Minar), is a synthesis of South Asian and Islamic Architecture, mostly built between 1199 and 1220. Its strong vertical presence has gracefully and powerfully dominated the skyline of New Delhi for centuries.

On each visit, I enjoy watching people interact with the buildings. Most are occupied with taking selfies, but I often see aspiring artists and architects sketching it, or young performers dancing or doing complex yoga moves around it. Both the Jantar Mantar and the Quatab activate and engage their surroundings and make room for expression and contemplation.

Jantar Mantar, New Delhi, India. built by Maharaja Jai Singh II of Jaipur, (1724 onwards). Image courtesy Avantika Bawa

[1] Tim Ingold, Lines: A Brief History, Routledge, 2007.

Vishwa Shroff’s artistic practice is firmly rooted in drawing, with a proclivity towards architectural forms that serve as compelling take-off points for a deeper contemplation on memory and our relationship with the material world. Her works explore the narratives of lived experiences that lay embedded within surfaces. Shroff trained at The Faculty of Fine Arts, MSU, Baroda and at the Birmingham Institute of Art and Design (UK). She has had eight solo exhibitions including ‘The Music of Buildings’ (forthcoming) at Tarq, Mumbai as well as several group shows. She has participated in a number of artist residencies, including Swiss Cottage Library, UK (2017); Paradise Air, Japan (2015); Clarke Griffiths Levine, UK (2012) and the Stiftung Laurenz, Switzerland. She was the recipient of the UNESCO-Aschberg Bursaries for Artists in 2011 and the Josuken Housing Research Grant in 2020. Shroff is the co-director of SqW:Lab and is represented by TARQ.

Avantika Bawa is an artist, curator, and educator based in Portland, OR, and often resides in her hometown, New Delhi, India. In April 2004 she was part of a team that launched Drain – Journal for Contemporary Art and Culture. www.drainmag.com. In 2014 Bawa was appointed to the board of the Oregon Arts Commission. She is currently Associate Professor of Fine Arts at Washington State University, Vancouver, WA.