An Interview with Michael Scoggins

Brantley B. Johnson

| Dear

God, Hello. I hope you are well. I am writing to you to tell you I think you are great. Thank you for all of my family and friends and all of the good Things you made. Thank you for making the Earth and I promise I will be good so I can go in Heavan. My Sunday school teacher says that you are all good and powerful. I asked my Sunday School why there are bad people in the World and why do they hurt other people. My Sunday School teacher says that Satan make people be bad. I wish that you would make him stop making people do bad things. I wish that you would tell people not to Listen to him and to do only good things and help others. Thank you for listening. I will brush my teeth and pray before I go to Bed. Amen. Michael S. |

|

|

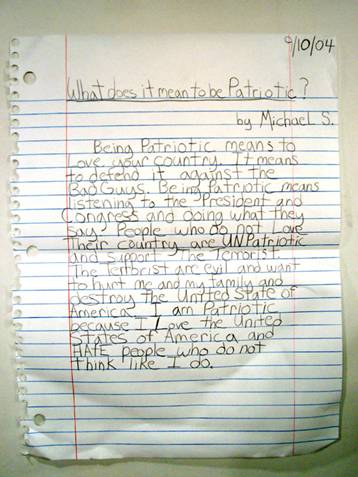

Michael

Scoggins, What Does it mean to be Patriotic?, 2004. Graphite, prismacolor

on paper, 67" X 51"

|

I recently had the opportunity to see one of Michael Scoggins' new textual renderings, where on a gigantic notebook page under the guise of his younger self, he thanks God for the good in the world. His Dear God (No. 2), a transcription of which appears above, was inspired by a conversation Scoggins remembers having with a childhood Sunday School teacher. Dear God (No. 2) is one of several new paper pieces created by the artist.

Scoggins, a Virginia native, currently lives and works in Savannah, Georgia, and his candid, brutally honest textual pieces are quickly bringing the young artist critical praise and international notoriety. Scoggins' work has been featured in such magazines as Art Papers, New American Paintings, and Beautiful Decay amongst many others. He received a fellowship to study at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in 2003, and is currently a M.F.A. candidate at the Savannah College of Art and Design. Scoggins is represented by the Saltworks Gallery in Atlanta, Georgia.

The artist's first solo show in New York in the Spring of 2004 at Priska C. Juschka Fine Art, 'Paper Works,' was more than a mild success. The Museum of Modern Art purchased four of Scoggins' paper pieces for their permanent collection, to be included in an upcoming drawing exhibition the museum has slated for 2006. In the months since the 'Paper Works' show, the artist has been in high demand: Scoggins' newest series of colorful comic book and superhero images debuted at Samson Projects in Boston in November 2004, and a solo show of the artist's textual works is set to open at Diana Lowenstein Fine Arts in Miami in May 2005.

Scoggins' newest paper pieces, created for a group showing at the Scope Miami Art Fair in December 2004, pay homage to the ubiquitous sheet of notebook paper on a scale that would bring delight to any child or adult viewer. With apparently naive penmanship and vocabulary, Scoggins re-lives both painful and triumphant childhood memories on his paper creations. The oversized spiral-bound notebook pages, which Scoggins creates by cutting large rolls of paper into the all-too-familiar notebook sheet shape, are complete with hand-drawn, instantly recognizable trademark blue and red lines. And although Scoggins renders each line by hand and carefully circle cuts each hole, the artist takes great care to ensure that each 'page' is identical. This element of the mass produced, culturally significant art object may call to mind the factory-produced work of the Warhol generation or, in terms of scale, Oldenburg's Clothespin. Each notebook piece is intensely labored over by Scoggins and possesses its own nuances of originality. At 67-by-51-inches, each work is almost exactly six times the size of the standard 11-by-8 ˝ -inch piece of paper.

|

|

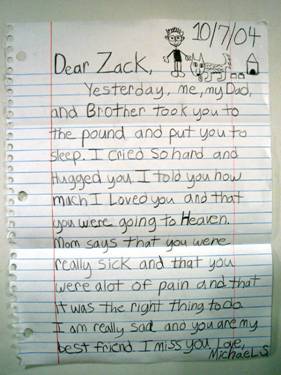

Michael

Scoggins, Dear Zack, 2004. Graphite, prismacolor on paper, 67" X

51"

|

This outwardly simple object that Scoggins creates, a sheet of paper, is the artistic vehicle on which Scoggins exposes himself and his most private thoughts and childhood traumas. Scoggins' notebook pages are a marker of adolescent self-discovery, mischief, and learning. When he has finished writing or drawing (he prefers Crayolas, Prismacolor pencils, and Sharpie markers) on a particular piece, Scoggins frays its edges and dirties its surface in order to 'authenticate' the work so that it takes on the appearance of a sheet of paper that has been folded, hidden in a child's pocket, or perhaps passed around by soiled hands. The results are narratives that deal with self-discovery and loss; loss that is negotiated through the cathartic process of writing the personal stories down. The artist signs all his works with the shortened penname 'Michael S.,' resurrecting a youthful grade school emblem of identity. Scoggins' voice is his own, yet this voice speaks in a language that is universal: it is the language of love, loss, guilt, and remembrance.

In his book The Pleasure of the Text, Roland Barthes wrote, 'I am interested in text because it wounds and seduces me.' [1] Barthes's words resonate when I encounter Scoggins' work; through the voyeuristic and pleasurable nature of reading, as a viewer one is seduced by the sincerity of the text and at the same time wounded by the underlying sadness in many of his letters. Scoggins' drawings deal with childhood loss but the works also display an agony over the loss of childhood. The question arises: do we ever really lose ourselves? Are we different people when we 'grow up?' Our desires and fears may remain the same; we only learn to articulate them differently.

Scoggins' narratives deal with personal tragedy and loss, but their creation is a recapturing of experience, and a reclaiming of self. Is anything actually 'lost' in the syntactical materialization of his experiences? Stories are no less sacred when transformed by being written down. The emotion remains the same, raw, only now revealed, exposed, and translated by a more mature hand. To verbalize visually is not to deny memory of its fleetingness or deny that distortion may exist, in fact, the oversized paper pieces deliberately play with that tension between distortion and authenticity. Scoggins does not expect his viewers to see the work and believe that they are precise replicas of experience; rather the elements of truth are found in the confessional nature of the work more than the technical expression. Since Scoggins values narrative genuineness above all in his textual pieces and these truths are his own, it becomes less of a question of what gets lost in translation but instead what can be gained. Perhaps when the truth is realized there is no loss.

When talking about art and language, Scoggins' said (author paraphrasing here), 'Sometimes I think artists hide behind the imagery they create. Why not just come out and say it?' It is in this statement that the power of Scoggins' work lies. He puts aside any potential embarrassment his narratives may bring him and comes out and just says it. With this knowledge of Scoggins' openness, I knew we would have a candid and revealing conversation when the artist agreed to talk about his new work with me. The following is the result of an interview conducted when I sat with Scoggins in his studio in downtown Savannah to discuss his text-based works in November 2004 and in subsequent conversations with the artist in early 2005.

|

|

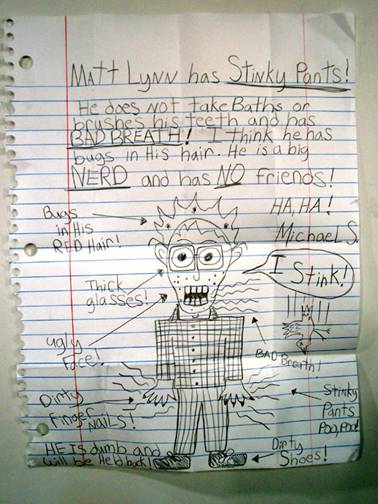

Michael

Scoggins, Matt Lynn has Stinky Pants, 2004.

Graphite, prismacolor on paper, 67" X 51 " |

Brantley Johnson: Your 'Michael S.' signature has become a staple of your textual works. We have spoken before about Robert Ryman's white canvases, where his now-famous 'RRyman' is the only definable imagery. In many ways I look at the 'Michael S.' in the same light, as having monumental importance in your work. How did this component, which has now become a consistent compositional element in the text pieces, come about?

Michael Scoggins: It's kind of funny, I think; the initial use of 'Michael S.' came about with the notebook drawings, it was about having the name Michael, which is a pretty common name, and having to tack on the 'S' in order to differentiate yourself from the other Michaels in the [grade school] class. That was the beginning of that-the idea of giving yourself an identity. Another reason that it started was that it was almost a dare. I was still painting at the time, still painting oil on canvas, and a lot of the students were signing their canvases on the front with these big, bold signatures, and a lot of the professors I went through school with really hated that, they hated the idea of a large signature, it reminded them of those 'Sunday painters,' and a lot of students were chastised for that. So in my mind it was a way of using the signature . . .

BJ: As kind of a rebellion?

MS: Kind of a rebellion, yes. I kind of took it as a dare, like 'I'll show you that I can do this,' and use my signature in a very bold way. It fit conceptually. And it is kind of a little joke with myself.

BJ: What were your paintings like before the shift to text paintings?

MS: Before the shift they were basically large scale, oil on canvas. When I first came to grad school I was pretty closed minded as far as what visual art was, I had that mindset of being a 'painter,' a painter using paint, using brushes on canvas. It was like walking around with blinders on, but that's what art was to me. Not until later on, about halfway through the program, did I start thinking in other ways. The paintings just weren't saying exactly what I wanted to say. What I was painting was basically Guston-esque cartoon characters, political icons, and things like that-very general. I didn't feel like they were very personal. I was trying to say something but I think that the medium was the incorrect one, and that's why I started to switch over to using pencils and markers, things that were very familiar and very primal. I feel that they have been successful because it's more of something that any person can identify with. Everyone draws when they are younger, everyone writes letters. So I think that's how the shift began-I had these ideas that I couldn't explain with paint-I felt more comfortable explaining them with other materials.

BJ: Also, when you are a child, everything is bigger than yourself, everything is oversized. And your notebook pages are oversized. Do you think that this is a way to put your viewers into the same kind of mindset that you have when you conceptualize the works? Are you maybe, in a way, making your viewers into children by placing them into an oversized world?

MS: Yes, I think so, that's pretty right on. I started with that scale, which is about six times the size of a normal piece of paper. Blowing them up was a definitely a way to put myself and the viewer back into 'that place.' I think that just having these large familiar images is-again, it goes back to that universal quality, just blowing them up, the viewers just instantaneously respond to that because it is something very familiar. Doing them at this scale, they command the space; command the room, when you walk in. Another reason that they are done in this scale is-once again going back to the idea of being a 'painter,' they are along the same scale as the paintings I was working on in the beginning. Here I can use broad strokes or be very loose and free and I feel that it is more natural working in this scale. I feel like that is something very important.

BJ: In terms of content, the text works are raw and personal in an often surprising way-when I read some of the letters I feel as if I am seeing something that I shouldn't be seeing, like stealing a glimpse at someone's diary. Are there any subjects that are just too sacred to expose? Have there been ideas for the textual works that in the end, you were simply too nervous to turn into pieces?

MS: The series has been a slow progression of opening up. I still feel there is a lot of uncharted territory to talk about. When I was painting, I felt very safe with the imagery I was using, and I think to be an artist and to be comfortable in what you are doing is not a good thing. It has to be about challenging yourself. Some of the first few letters I produced-it was very nerve-wracking to show them publicly, because I was exposing my life, they were events that actually happened. But it kind of became a thrill to be able to do that, because if the content of the works are making me uncomfortable to show them, then it is probably making the viewer uncomfortable to read them, and that's where the 'connection' happens.

BJ: When did this nervousness begin, was it just perhaps on opening day of an exhibition, or did you always have these nerve-wracking feelings, as you created the works?

MS: I think it was before hand, but there was a definite nervousness when they were first shown publicly. But even when I am thinking about them, sketching ideas down in a sketchbook, I am always like 'Should I do that?' or 'Can I say that?' and it is like a personal battle trying to overcome these fears. I once did a series of journal entries, exposing very personal things, and I did want the viewer to feel like they were a voyeur, looking into my personal thoughts. But everyone has these events happen to them (not mine personally) but something similar. I expose myself so that the viewer can think back to something similar that happened to them.

|

|

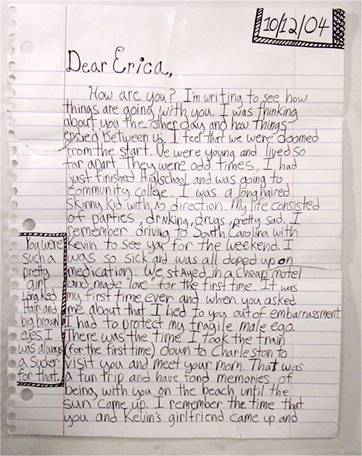

Michael

Scoggins, Dear Erica, 2004.

Marker on paper, 67" X 51" |

BJ: You once told me that while exhibiting a piece concerning a very emotional breakup with a girlfriend, people at the show pulled up chairs in front of the work. Were you surprised that your work had been so therapeutic for your viewers? I know that creating the works is personally very cathartic, but are you surprised by viewer responses, and does that help your anxieties about exhibiting these works?

MS: I think so. I was initially really shocked. Using text-based work is kind of a risky thing. I initially didn't think people would react the way they have, yet to have people sit and read every word was kind of fascinating, watching that from afar, watching these people read very personal moments in your life, it's very strange. There is that theory of the 'three second rule' in the world of art: that the average person will only look at a work for three seconds before moving on to the next one. So to have people sit in front of your work for however long it takes them to read from start to finish-it is very fascinating, and I really wasn't expecting that. I thought people would maybe read the first sentence or two, get the gist of it, and then move on. So it makes me feel really good that the work has that impact-that people want to read it from start to finish.

BJ: I think that one of the most striking aspects of your work is your dedication to authenticity-all of your pieces, whether letters to God, deceased pets, or past girlfriends all make reference to actual events in your life. While some of the misspellings are 'faked,' the emotions are not. Have these choices to keep the text authentic had any negative consequences for you or your work?

MS: I don't know if there has been anything overly negative that has made me rethink what I am doing. I do write about very personal things and write about other people that have been in my life; a lot of people are from the past, people that I no longer have contact with. But there have been cases where I have written very personal things about people that are still in my life, and that has gotten kind of a negative response [laughs], because I am laying it out, and exposing them as well. And I do feel uncomfortable with that sometimes because I don't know if that is the right thing to do, but then I rethink it and it is not really about them, but about my life and my experiences. They just happen to be a part of my life at that time. As far as keeping it authentic, I think a lot of the misspellings-some are tweaked, but a lot of them are real misspellings that I find in my old letters. The handwriting is mine, and I think that is important. I have very poor handwriting, so it kind of works out [laughs] that I have been able to take this inability to have perfect penmanship and turn it around and use it as a key element in the work.

|

|

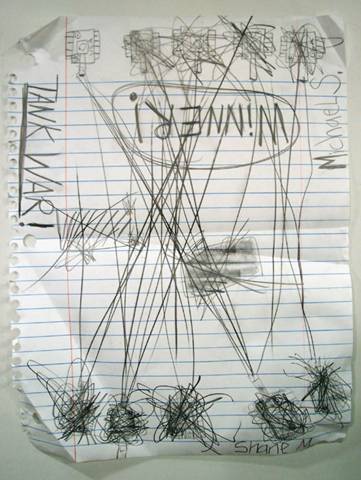

Michael

Scoggins / Shane Moore, Tank War!, 2004.

Graphite, prismacolor on paper, 67" X 51" |

BJ: Most of the pieces that are going to Miami are in this 'letter' format, but one work that sticks out is Tank War, a collaborative piece you did with fellow artist Shane Moore. I actually had the pleasure of being here while you and Shane were making Tank War, and it kind of turned into a bit of a performance piece. As Tank War began, I was struck by how you and Shane seemed to get into this schoolboy 'character,' but as the performance continued there was also something very natural happening, and a point at which I realized that the two of you weren't really 'acting' at all. Tell me about the process of making Tank War.

MS: Tank War is based on the idea of a game I played in elementary school. Two people sitting on opposite sides of a desk draw 'tanks,' and you whip your pencil across the page to make lines and 'blow up' the other person's tank. Whoever destroys a tank first wins. I have been trying to do more collaborative works, that has become important to me; it is that aspect of letting go, letting go of control. In the past I had a hard time dealing with that. It's funny, I think that being an artist, it is important to be able to not just role-play, but actually become. But I also think I am thirteen at heart and always will be. I think Tank War is an example of Shane and myself not acting, but actually being. And also enjoying that process and having fun, which the game is all about. And there were underlying issues of a power struggle between us I think [laughs] and issues like that, but I think the purity of it is the key to its success. I think in all of my work, I am that person, I am that age, or at least myself at that age, and there isn't acting involved. It's more of getting into that mindset. That is important, because if it were anything other than that, it wouldn't be sincere.

BJ: What do you think are the largest misconceptions people have about your work?

MS: I think a lot of people neglect to see the underlying meaning of the work. They might see it at face value, as 'cute' or 'funny.' It bothered me at first but I'm okay with that now. I realized that everybody takes what he or she wants from a piece of art. I'm just happy to get a response at whatever level the viewer sees it. I also include a lot of things that only I know about so I can't expect people to see that. I remember one incident where I was having a conversation with a former professor in the hallway at school and a lady came up to us and as we introduced ourselves she recognized my name from my work she had seen. She commented on how much she loved it and how funny it was and left it at that. After she left my professor asked me how I felt about the comments and I told him I gotten use to that sort of response and it doesn't worry me if some people don't get the deeper aspects. What I do enjoy is that a large amount of people respond to it in a positive way at many different levels. It's getting a reaction that is important.

BJ: What kinds of distortions exist in the notebook works, both in terms of technical expression and concept? Do these distortions take away from the 'truthfulness' of the narratives?

MS: There are some distortions in my work. I do sometimes manipulate a narrative from my youth to fit a particular concept for a piece. Most are based on memories and I believe that memories are very flexible. It is fascinating what we remember but it is also interesting to think about what we don't recall. People remember the strangest things; it's funny how certain moments 'stick out.' I think a lot about how memories are manipulated in the human mind over time, even to the point where I wonder if memories are even genuine or somehow they have been implanted by outside influences. But the fact is that all of the work is based on occurrences in my life. It is the 'truth' that I know, but I am recalling them through my adult mind, so the context has changed. I feel that distorting does not affect the 'truthfulness' because things are already distorted. I think the key factor in the work, as a whole is to approach it in a sincere way and maintain honesty. I'm not pretending to be something I'm not.

BJ: What role does irony and humor have in your work?

MS: I love irony and humor in art. They are both a huge part of my own work. I find myself laughing at things as I create a piece. Unfortunately only I understand most of the irony and humor, since I am the subject matter of my work and only I have that direct knowledge of why certain aspects are funny. It's like a silly 'inside joke' mostly about reliving those moments and how absurd my thought process is. There are other levels where I think people find the irony or humor because they have similar memories and can relate to mine. I use irony a lot to make a point with some serious issues that I deal with in the work.

|

|

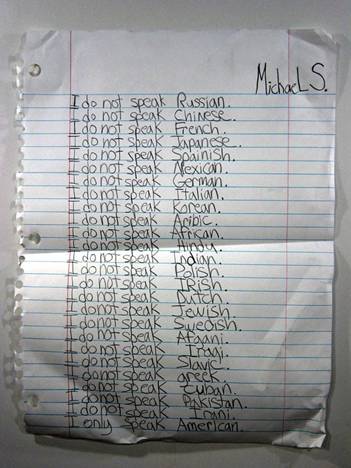

Michael

Scoggins, I Do Not Speak, 2004.

Graphite, prismacolor on paper, 67" X 51" |

BJ: The text works typically operate under the grammatical guise of this child, the young Michael S., which is you, yet one of the new text pieces displays a tension between the emotional thought processes of the adult Michael, and the young Michael. I am thinking here of Dear Erica, a work in which you write a letter to an ex-girlfriend. Do you ever feel that there is ever a narrative conflict between Michael S., the child, and Michael Scoggins, the adult?

MS: When I first started the series, I was very adamant about doing it-keeping the continuity-there was a steady progression. I started at a very young age, and 'Michael S.' slowly grew up. But I since have abandoned that. At first it was important to have this structure on how the work was produced but I have now gotten comfortable in jumping around, because it is all aspects of my life. I don't feel the need anymore to start at one point and end at another. I'll work on a mature letter one day and a child-like one another day.

BJ: So it has been a conscious choice to have 'Michael S.' age and grow up throughout the art making process?

MS: At first, yes, that was the overall concept, to have everything under this one 'umbrella.' But now I feel like it is not necessary to have that progression.

BJ: In terms of influences, we have talked before about our shared appreciation of conceptual artists like John Baldesarri and Joseph Kosuth, who use text in a playful, unconventional way, and you mentioned Phillip Guston. Do you consider artists like these among your biggest influences?

MS: [laughs] That's a hard question to answer.

BJ: Okay, or maybe people that you are exposed to now?

MS: Well, I have a lot of 'idols' in the art world . . . I tend to be drawn more to a quirky kind of art that when you first look at it, you are like 'wow that's kind of funny,' but it is done in a really intelligent kind of way, it's smart, but eventually you start to get the feeling of an underlying seriousness to it. Baldesarri is really funny, but he is also really smart. Another example is Tom Friedman, who I think is a genius. His work is great; I can't gush about it enough. Kara Walker is another artist who has had a big impact on me. Her work is amazing and beautiful, but also very simple. I think simplicity is very important. When things get overly complex, I think a lot of the deeper message can be lost. That is the philosophy I tend to take: keep it simple, keep it real. Gary Simmons was also a big influence on me. He was doing these icons on chalkboards and erasing them, and that led me into my chalkboard series. He was using icons as well to delve into racial issues. And also a lot of my peers, people who are around me are a large influence, in terms of sharing ideas about the pieces, and reactions and discussions. And a lot of kids influence me. I have actually started files of things I have collected, and traded drawings with kids [laughs] and things like that, and that's a lot of fun. So I reference contemporary children's drawings as well as my own that were done twenty-five years ago.

|

|

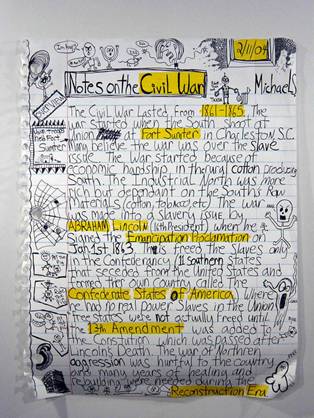

Michael

Scoggins, Notes on the Civil War, 2004.

Marker, highlighter on paper, 67" X 51" |

BJ: Drawing on the theme of 'Lost in Translation,' and the idea that verbalization of experience may create a loss, I want to address this notion in your work. Loss is a thematic force in the text-based drawings, but in a bigger sense, is also a very abstract idea. What if anything, do you think gets 'lost' over the years?

MS: Well, a lot of my works do deal with loss. I think as we grow up there is a loss of innocence of course, a maturing. I think that is a sad thing. I grew up in a very rural area, so I can really only talk about my experiences as a child, but there is an odd adult mix that comes into it. And I think that is where a lot of the loss is. There is this nostalgia that comes with recollecting these events, and being like, 'Well, that was a sad day,' but I feel as people get older the idea of-the older part of me can take these old moments and re-tell them through the work and then begin to have adult ideas about them, if that makes sense. Dealing with these ideas of loss as a child, but also as loss as an adult, whether it is a loss of that innocence, it's definitely a reflection back to an era that is gone. But a lot of those moments weren't happy moments. I think I tend to focus on the moments of loss because those are so engrained in my mind, things that are still very clear to me today. But those are the experiences that made me the person that I am.

|

|

Michael

Scoggins, Dear God (No. 2), 2004.

Graphite, prismacolor on paper, 67" X 51 " |

BJ: How do you respond to kinds of criticism regarding your work that argues that the engineering of naiveté compromises the memories?

MS: I haven't had a lot of criticism in that area. The drawing is mine and the way I draw is another tool to convey my concept. It is my mark and my memories so I don't see where there is a compromise.

BJ: An exhibition of your textual works is set to open in Miami in early 2005. Will you remain working with the notebook pages or do you plan to move into a new direction for your next show?

MS: I intend to show all new work in Miami. They will be the notebook pages. I have started the comic book series, which I first showed in Boston. I am hoping to show those again near the end of 2005 at Saltworks in Atlanta. I see the comic pieces and the notebook pages as different categories in one body of work. I am starting to think about larger projects, multiple pieces and such, but that's in the future, so stay tuned.

©2005 drain magazine, www.drainmag.com, all rights reserved