Elisabeth Gambino

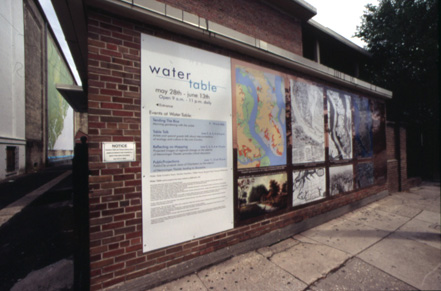

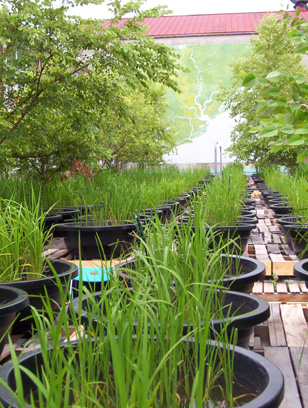

Last spring's Spoleto Festival featured a visual artwork which addressed multiple local and global concerns. Water Table was an installation conceived by curator Mary Jane Jacob and artists Kendra Hamilton, Walter Hood, Frances Whitehead and Ernesto Pujol. "Installation" is a complicated euphemism, but in this instance it translates into 3,000 living Carolina Gold rice plants mounted on an industrial platform in the middle of an elementary school courtyard. 300 circular black ponds elevated three to four feet above the ground, with green shoots sprouting through eye level truly transform an urban school courtyard. The effect is enhanced by a magnificent forty foot map of the Low Country, rice waterways, and striking blue chairs are placed throughout the space inviting visitors to sit in this contemplative space: a rice paddy in downtown Charleston.

Tying the piece to water is essential in a city like Charleston, which is inundated by the elemental force at least twice a year. The port town is built on a peninsula and was one of two principal importing site for slaves in the antebellum period. Once acclimated to Charleston, slaves were primarily employed to construct and maintain the rice paddies on vast aquaculture plantations outside of the city. Two major thruways of Charleston, Market Street and Spring Street, are built directly over underground springs, increasing their vulnerability to flooding. Charleston was the site of experimentation with the first successful offensive submarine attacks, the crew of the Hunley being recently discovered underneath the football field of the Citadel. Today, Charleston's waterways are sites of dispute and development. The livelihoods of the famous Mosquito Fleet fishermen and their families have been edged out by recent incursions of the tourism industry. Pollution is also a major factor affecting the lives of Low Country families who live on the freedman's plots north of Charleston, as industry runoff affects the springs and creeks which could otherwise be used for fishing and leisure. Naming the exhibit after the predominant landscape calls attention to the fact that the lifeblood of the city still rises and falls with the water table. In Charleston, ecology, sociology, and economy meet in a political economy of water.

The artists opened the exhibit with a public forum featuring students from Memminger Elementary school doing a "rice dance" led by Kendra Hamilton, and an evening program featuring elders from the Gullah Gichee nation, the mayor of Charleston, an agricultural scientist, and a historian of rice. This is a small reflection of the vast community research behind the project. The thinking behind Water Table is broad enough to include interviews with representatives from almost any social group connected to water in Charleston and the Memminger site: the descendants of freemen on the outskirts of Charleston, the retirement home across the street, the public housing community next to the elementary school, fisheries anthropologists, shrimpers, civil engineers, politicians and professors.

"Table Talk," a portion of the art project, brought some of this research to light, featuring conversations with local experts on rice culture. Discussions on the veranda around the rice table begged the essential question of the program: how to move from Charleston's past, through the Charleston of the contested present, and into the Charleston of the future?

Rice was a particularly on-target choice of materials, as the history of its cultivation is central to the history of colonization and slavery. Many of the Charleston audience members commented they had grown up hearing about the history of rice, and eating it two or three times a day, but never knowing what the plant looked like. This year has also been declared the international year of rice by the United Nations, in an effort to draw attention to the importance of the crop as a critical food staple for billions of people around the world.

Civic-minded at its heart, the project was designed to be environmentally sound and to spiral out into continuing education and awareness. This more than makes up for the tucked away "secret garden" character of the original installation. Instead of a single isolated event or single public art project, Water Table will lead to perhaps hundreds of similar experiences, as its various components are disassembled and distributed to area educational facilities - at no charge.

Mary White heads up a summer-school program for kindergarteners based at the College of Charleston. She is receiving several pots of rice and will incorporate it into the "rice curriculum" she is developing for K-5 students in Charleston and Carleton County Schools. Students will learn about the cultural history of rice, the labor needed to maintain a rice economy, the art, music, science and customs associated with rice cultivation. Seventy-nine pots of rice are going to the Wings-for-kids after-school program. Under the supervision of Bridget Laird and Virgil Smith, students from the Memminger Elementary School will incorporate the plants into lessons about science, math, and writing to work towards higher scores on state exams. The artists have also placed pots of rice to be included in interpretation at historic sites such as the Charles Pinckney House, the Edmonson-Alston House, the Hampton Plantation, Old Santee Canal State Park, Boone Hall, Magnolia Plantation, and Cypress Gardens. Interpretive programs such as that at Boone Hall focus on teaching school children about the historical economy in the Low Country. Being able to see how the plants grow and imagine the immense labor of sludging through the swamps to plough and harvest the grain will greatly add to understanding the extensive manual labor involved in rice cultivation. The slender green stalks, rippling under the slightest breeze, are a strong visual statement on the fragility of agriculture and our relation to the earth.

Frances Whitehead and Walter Hood possess an astounding expertise in plants and landscape. Whitehead has long been working with plants and gardens, designing public gardens in color themes and as decorative chart and graph illustrations of scientific facts. Whitehead is fascinated with the integration of art and sciences, she stated that applying art as technology to question the politics of urban development was a new experience for her. She looks forward to investigating these ramifications of her public works further in the upcoming years' installations. Walter Hood was featured last August in the Cornerstone Festival of Gardens, the first gallery-style exhibition of avant-garde landscape architecture in the United States. He has exhibited with the Smithsonian, Harvard University, and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. His work is extraordinarily socially engaged, and Hood has won numerous awards for his process of lengthy conversation with residents to discover the natural thruways of spaces to be redesigned, thus arriving at startlingly simple and effective ways of urban redevelopment through landscaping. In his practice, Hood seeks to fulfill a community's living needs while simultaneously recognizing history and preparing for change. Hence the team assembled to work on this cycle of installations in Charleston is at the forefront of new urbanism, with a strong post-feminist approach to community-building through visual art practice.

Pujol and Jacob are intimately involved in the building of this community of common interests from initially disparate sources. Ernesto Pujol comments, "For me, Water Table connected intimately with many other large-scale installations I have done where large tables have been my centerpieces/focus: The Picnic (1996), at the Bronx Art Museum, NY, Saturn's Table (1997), Second Johannesburg Biennial, South Africa, Memories of Surfaces (1999), RISD Art Museum, Providence. All these had grand banquet tables as the symbolic sites/domestic topography on which history was remembered, masculinity was shaped, and whiteness was defined." For Pujol, banquets always recall Judy Chicago's Dinner Party, the banquet of the women forgotten or misrepresented by history, with ceramic plates and embroidered settings with distinctly Iannic forms. Jacob is also distinctly connected with a feminist lineage in public art, having worked with Suzanne Lacy on Full Circle, an installation of 100 boulders in downtown Chicago, calling attention to the vast feminist history in the city and its failure to erect a single monument to any of its dozens of famous female citizens. Jacob's practice is clearly tandem to Lacy's multiple projects around "conversations" on a theme such as her Crystal Quilt, on aging, in Minnesota, or No Blood, No Foul on youth-police relations (Oakland, 2003). Jacob and Lacy also collaborated with Rick Lowe and other artists on the previous cycle of installations in Charleston, Evoking History.

The current cycle in Charleston is distinct from Jacob's previous work there for its refusal to be stuck in the past and its determined focus on the future: a tall order for a city bent on marketing its nostalgia. Water Table may rise or fall after the initial crop of 3000 plants is harvested. But the reusable pots, under careful supervision, can lead to new growth. Water Table, more than most "art objects" we encounter, will continue to multiply its meaning and utility. The living plants it contains will be "recycled" and transformed into teaching tools and trigger points for wide-ranging, regional conversations. The project continues with the same team over the next few years, and many different venues have been proposed, ranging broadly from an orchestra education program for Charleston high school students to the renovation of a boat from the Mosquito Beach Fleet. Keep your eyes on Charleston this summer to see where Jacob will take public art next.

©2005 drain magazine, www.drainmag.com, all rights reserved