Psychogeographical Boredom

Julian Jason Haladyn

“Boredom is counterrevolutionary. In every way.”[1]

Crisis of Culture

The Situationist International (SI) belongs to one of the terminal phases in the crisis of culture.[2] This crisis, which can be traced back to the beginnings of modernity, represents one of the fundamental problems of the interrelationship that developed primarily in the nineteenth century between culture and capitalism. In the 1957 ‘Report on the Construction of Situations’ – a key document in the founding of the SI – Guy Debord states:

As a condition of modern culture, one that has become increasingly exaggerated or hyperreal in the aftermath of World War II, this crisis has been the focus of all activities and strategies developed by the SI, which aim to counteract the effects of this ideological decomposition. Given the fundamental relationship between capitalism and the city, as the primary site of commercial activity; it is no coincidence that the city functions as the material ground for the SI critique of culture. This critique is most prominently manifest in their psychogeographical research, which employs numerous methods of observation and experimentation that involve ‘concrete interventions in urbanism.’[4] It is on psychogeographical grounds that the SI confront this cultural crisis.

The strategy of engaging in concrete interventions within the space of the city, specifically as an attempt to counteract the effects of ideological decomposition, has a long history in modern culture, dating back to the wanderings of the flâneur. In the figure of the flâneur or urban dandy, Charles Baudelaire ascribes the major site of resistance to the modern city; because he – the flâneur is constructed as masculine[5] – walks the streets indifferent and distant, finding his home only within the anonymous passing of the crowd. The flâneur’s relationship to emerging commodity culture is complex and even contradictory, depending fundamentally on the value of novelty and the concept of the new. As Walter Benjamin notes in The Arcades Project:

The flâneur’s dependence upon novelty or newness as a ‘last line of resistance’ ironically feeds into commodity culture, which in turn formulates a cultural history that negates the intended resistance. This is most evident in the fact that the department store, in encouraging people to stroll aimlessly through its commercial space, ‘makes use of flâneurie itself to sell goods.’[7] This modern history of culture, which emerges primarily through the work of Baudelaire, becomes embodied within the display and experience of newness in the collective form of the spectacle; a key element within the development of the commodity, which Debord cites as being the primary impetus causing the crisis of culture.

For the SI, the spectacle functions as a focal point for their attack on capitalism and commodity culture. As Debord states in the opening lines of The Society of the Spectacle, ‘The whole life of those societies in which modern conditions of production prevail presents itself as an immense accumulation of spectacles. All that once was directly lived has become mere representation.’[8] Separated from lived experience or direct use value, people within modern commodity culture experience alienated representations produced through the newness of spectacles. ‘The spectacle,’ Debord continues, ‘is not a collection of images; rather it is a social relationship between people that is mediated by images.’[9] In focusing their attack on the spectacle, the SI was attempting to disrupt this social relationship and undermine the mediation of cultural imagery that renders everyday life a mere representation or simulacra – which often appear as if directly lived because of the newness or novelty of presentation. The image as commodity is necessarily independent of use value because it exists only as representation. It is therefore an example of high capitalist production, in which what is produced is virtually pure exchange value in the form of the ever-new spectacle sold to consumers. In this manner, the spectacle becomes the chief product of Western culture and society.[10] As one of the primary mediating factors in the modern subject’s relationship to the social world, the spectacle is the driving force of the progression of capitalism and commodity culture, which in turn serves as a means of structuring and even defining the experience of the urban space of the city. The SI practice of psychogeography, which Debord defined as a process of research and study that examines ‘the exact laws and specific effects of geographical environments, whether consciously organized or not, on the emotions and behavior of individuals,’ aimed at studying these influences.[11] By making visible the laws and effects of the urban environment on individual subjects; psychogeographical research attempted to formulate an alternative urbanism that undermined and even eliminated the alienating effects of the capitalist culture.

Image 1: Mémoires

As a practice, psychogeography represents a means to study the functioning of the spectacle within consumer society in order to more clearly understand and counteract its processes of domination over everyday life. The psychogeographical projects of the SI involve direct interventions into the psychological and physical space of urbanism, engaging the city not as alienated observers but as participants in the constitution of society. As a state of mind, one can see psychogeography conjured up or represented in Debord and Asger Jorn’s collaborative book Mémoires, which as a text, Simon Sadler states in The Situationist City, ‘left readers with the task of negotiating Jorn’s inky dribbles through Debord’s collage of text, maps, and illustrations.’[12] This work was produced through the process of détournement, a means by which ‘preexisting artistic elements’ are directly taken and reused in the production of ‘a new ensemble’ that changes and often inverts the previous meanings or associations of the appropriated materials.[13] In addition to negotiating the physical obstructions caused by Jorn’s ‘inky dribbles’ and the collaged material arranged by Debord, readers of Mémoires are forced to negotiate the preexisting cultural elements – primarily from mass produced sources – used in the assemblage of the book and thereby directly confront the manner in which commodity culture mediates social relationships through images.[14] The segmented and decontextualized presentation of the imagery can be seen as reflecting, or making visible, the alienation of modern culture – literalized in the spaces that visibly separate various parts – while the colorful splatters of paint re-unite these fragments into a new wandering narrative that is fundamentally subjective. Each reader will discover a different text within this book. This emphasis on the individual to activate the text is particularly significant when considering the reconstituted maps in Mémoires, which presents the space of the city as a social relationship between urban representations that are mediated by subjects or readers. In these maps, urbanism is presented as a psychogeographical détournement, communicating through its subjective negotiability – highlighted through the simultaneous separation and integration of elements – the ‘inability to enshrine any inherent and definitive certainty’ in the space of the city.[15]

Image 2: Mémoires (map)

As the whole of Debord’s The Society of the Spectacle makes clear, the spectacle is based upon the subjectÕs fundamental alienation from the world, which results in the subject’s increasing dependence upon the newness of products that mediate relationships in the world of the city. In other words, the spectacle is a temporary fix to the prevailing aspects of alienation within modern culture and must be consistently replenished with ever-new spectacles: subjects who do not maintain their engagement within this procession of newness experience a sense of cultural meaninglessness or banality known as boredom. ‘Even in its most quotidian manifestations,’ Elizabeth Goodstein notes in Experience without Qualities: Boredom and Modernity, ‘boredom embodies a specifically modern crisis of meaning.’[16] As the virtual antithesis of newness, boredom can be seen as a byproduct of the constant need for novelty that has come to define modern life. ‘If boredom increases,’ Lars Svendsen tells us in A Philosophy of Boredom, ‘it means that there is a serious fault in society or culture as a conveyor of meaning.’[17] In order to maintain the product of the spectacle, commodity culture produces a need for the new that is endlessly perpetuated in the name of cultural progress. ‘Behind the glitter of the spectacle’s distraction,’ Debord informs us, ‘modern society lies in thrall to the global domination of a banalizing trend that also dominates it at each point where the most advanced forms of commodity consumption have seemingly broadened the panoply of roles and objects available to choose from.’[18] In order to maintain the need for newness, commodity culture fabricates new social roles and cultural objects for consumption. The result, as Debord describes, is a banalization of life through the increased meaningless of elements or products used to maintain a subject’s relationship with the world. In other words, behind the glitter of the spectacle lays the specter of boredom and the crisis of modern culture.

Bored in the City

For Baudelaire, the figure of the flâneur or dandy represented a means of critiquing modern culture through a directed engagement with the space or geography of the city. It is important to stress that this critique was based upon the active practice of a directly lived subjective intervention into the everyday urban environment of the streets and not a mere theory or representation. As such, the flâneur or, more generally, the urban stroller became a model for future critical engagements with the metropolis. This strategy of the flâneur or dandy functioned as the primary means of critiquing the product of the spectacle, particularly in the realm of art. Goodstein observes that ‘the attempts of successive avant-gardes to turn their boredom into art would continue to animate bohemias well into the next century and beyond,’ even though ‘the attitude of bored withdrawal had ceased to be the possession of the creative few.’[19] In fact, the democratization of boredom – as Goodstein terms the spread of boredom from the nineteenth century to present – can be seen as evidence for the necessity of such a strategy. If boredom is a byproduct of the modern subject’s increasing dependence on the spectacle of the new to mediate or provide meaning for her/his life, a critique of this process must be waged through direct intervention into the geography of this boredom.

As is evidenced by the literature, boredom has generally been perceived as a social ailment or problem resulting from a lack of subjective meaning within modern life. According to Arthur Schopenhauer, a subject’s life ‘swings like a pendulum, back and forth, between pain and boredom, both of which are in fact its ultimate constituents.’[20] For Schopenhauer, these two poles represent the subject’s inability to achieve what it desires or even to fail to desire at all. It is in ‘the game of constant passage from desire to satisfaction and from the latter to a new desire’ that he defines modern existence: if this transition is quick it leads to happiness and if it is slow it leads to suffering, but if it grinds to a halt it becomes ‘frightful, life congealing boredom, faint longing without any particular object, deadening languor.’[21] In other words, such life congealing boredom is one of the constituent factors within the lived existence of modern subjects precisely because of their inability to consistently and quickly find passage from desire to satisfaction within modernity – specifically in relation to the influx of consumerism and capitalism into subjects’ everyday lives – resulting in a fundamental lack of subjective meaning. For Søren Kierkegaard, the meaninglessness associated with this state of boredom had profound ethical and moral implications, most notably in relation to people’s actions; as he states quite simply and directly: ‘Boredom is the root of all evil.’[22] Kierkegaard is particularly adamant to distinguish idleness, which he perceives as being a state of potentiality or ‘the true good’ that defines a ‘level of humanity,’ from the ‘demonic pantheism’ of boredom.[23] For both Schopenhauer and Kierkegaard, the state of boredom is inherently linked to the relationship between the modern subject and the everyday world of modernity, in which a subject experiences a lack of meaningfulness within their lives. As Martin Heidegger notes, the characteristic of boredom ‘belongs to the object and is at the same time related to the subject.’[24] This hybridity, as Heidegger himself refers to it, functions to make studying boredom problematic, specifically because as a condition it swings like a pendulum back and forth between the subjective experience of people and the objective cultural realities of modern life.

Discussing the Freudian and the Marxist traditions, Fredric Jameson notes in Postmodernism or, the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism that boredom ‘is taken not so much as an objective property of things and works but rather as a response to the blockage of energies (whether these be grasped in terms of desire or of praxis). Boredom then becomes interesting as a reaction to the situation of paralysis and also, no doubt, as a defense mechanism or avoidance behavior.’[25] In virtually every discussion on the subject, the state of boredom is positioned as neither fully located within the subject nor the object of modern culture, but rather as a mediating factor or psychological element within the relationship between subject and object. Although, as is evident in Jameson’s statement, the consideration of boredom in such a relationship is not strictly a negative one – as is inferred or stated by Schopenhauer and Kierkegaard – but rather can be seen as providing modern subjects with a potential means of defending or avoiding the ailments of modernity itself; most prominently the meaninglessness of commodity and capitalist culture. In ‘Boredom and Social Meaning,’ J. M. Barbalet states that ‘boredom is an emotional safeguard of meaninglessness and a defense against meaninglessness.’[26] In other words, it is through the meaninglessness of boredom as a mediating factor in the relationship between the subjective and the objective realities within modern culture – the psychological and physical desire or energy of the subject that is blocked by everyday life – that a critique of capitalism can be waged.

My contention is that boredom, or the attitude of bored withdrawal, has come to function as a major element in the avant-garde’s attempts to combat capitalism – albeit, not one that is typically venerated or theorized. Benjamin is one of the few exceptions to this oversight. In The Arcades Project he devotes a section to ‘Boredom, Eternal Return’ that examines through a series of commentaries and quotations the topic of boredom, which most importantly connects boredom to the urban space of the arcades through a psychology of subjective engagements with the city. In a rather poetic statement he writes:

For Benjamin, the arcades function as an embodied cultural history based within the lived quotidian experiences of the everyday, an experience that necessarily included boredom. His critique of capitalism is therefore sheathed in the discussion of the arcades and, more significantly, in the cultural activities that can be seen to populate the history of this urban space. In The Arcades Project, Margaret Cohen states, ‘Benjamin set out to capture the psychological, sensual, irrational, and often trivial aspects of life during the expansion of industrial capitalism the trivial, mundane, and everyday aspects of lived existence within the city, epitomized in the state of boredom, that Benjamin sees the greatest potential for a critique of capitalism.

In ‘Benjamin and Boredom’ Joe Moran attests that, ‘Benjamin’s understanding of boredom thus anticipates the work of Situationist philosophers such as Guy Debord and Raoul Vaneigem.’ He continues by stating that ‘boredom is linked to what Vaneigem calls “survival sickness”, a product of the shift from a society based on mass production to one based on consumption and spectacle.’[28] But, whereas Benjamin conceived of the experience of boredom as ‘a warm fabric’ that hides potentially ‘lustrous’ qualities, the SI viewed boredom quite simply as counterrevolutionary – a polemical statement reminiscent of Kierkegaard’s proclamation: ‘Boredom is the root of all evil.’[29] As a pronounced psychological epidemic of commodity culture, one that increased in severity in the post-war expansion of capitalism, the experience of boredom can be seen as feeding into the consumption of the spectacle as product, which society provides as the bored subject’s main antidote. For the SI, therefore, the state of boredom represents an extreme manifestation of the modern subject’s alienation from the world, one that is reflected and amplified through the structuring of everyday social life. In fact, as Moran states:

The primary critique that Debord wages in Society of the Spectacle is based upon the exploration and consequences of this separation. In section 27, for example, he directly comments on the manner in which capitalism has increasingly transformed the principle of work ‘into a realm of non-work’ or leisure, so that all activity – including work, leisure, and ‘free’ time – is ‘forcibly channeled into the global construction of the spectacle.’[31] In other words, even when modern subjects are not engaging in productive work they are consuming cultural products and therefore still supporting the mediation of the spectacle upon their lives. What Debord and the SI failed to recognize was that boredom represents the modern subject’s inability to be seduced or enamored by the spectacle, the resulting sense of meaninglessness making the interrelated system of culture and capitalism visible.

The psychology of boredom, as a particularly modern crisis of culture and meaning, is therefore an important point of departure for SI critiques of capitalism because, as a product of the interrelationship of the spectacle and modern culture, it exists in direct relation to the space of the city as a living urban environment. Discussing the links between boredom and capitalism, Goodstein notes that boredom ‘came to stand for a retreat’ from consumer society, representing an ‘alienation from and not of society.’[32] In other words, boredom is seen as a retreat or escape from the spectacle because it makes visible, through the lived reflections of an alienated individuation, the subject’s isolation from society. The modern experience of boredom, far from a simple societal nuisance, represents a cessation of the of the spectacleÕs ability to mediate social relationships between people. ‘Boredom contains a potential,’ Svendsen states:

Along with its function as a motivating factor in the continuation of the cycle of commodity engagement – in which the bored subject returns to the spectacle for entertainment in order to fill the emptiness – the direct experience of separation and alienation from society, when in the state of subjective boredom, represents the potentiality for a positive turnaround, in which boredom functions as a key motivating factor in the social critique of capitalism.

This is precisely the response of the SI to their own boredom, which they rightly perceived as counterrevolutionary – given that the standard relief that culture provides for this state of meaninglessness is more of the same ever-new commodity spectacles. ‘We are bored with the city,’ Ivan Chtcheglov begins his 1953 ‘Formulary for a New Urbanism.’[34] It is significant that this key proto-Situationist text, one that aided in the formation of the SI discourse on new urbanism, would start with this declaration – repeated at the end of the first paragraph – of communal boredom.[35] In this statement, Chtcheglov delineates a shared subjective mood or attitude regarding the present state of cultural history in general and the city, as a site of lived culture, in particular. ‘They were bored with art as they knew it, bored with politicians, bored with the city, and bored in the city. The city had become banal, as had art and politics. Banalization was a mental and material disease afflicting life in general.’[36] It is this mood or attitude of being ‘bored’ that serves as a catalyst for the revolutionary project of the SI, specifically in relation to the meaninglessness of lived experience perpetuated within the everyday space of the city.

On the Construction of Psychogeography

The entire SI project can in one way or another be seen as a direct response to the modern city, which serves as the primary site for their interventions or situations. The construction of situations, as a mandate or central idea of the SI, according to Debord involves ‘the concrete construction of momentary ambiences of life and their transformation into a superior passional quality.’[37] These constructed situations were seen as a means of resisting the hyper-expansion of capitalism into all aspects of life, including leisure or free time, and therefore the ground for this situation-based resistance is the focal point of the spread of commodity culture: the urban environment of the everyday city. ‘Our situations will be ephemeral, without a future. Passageways. Our only concern is real life; we care nothing about the permanence of art or of anything else.’[38] Similar to Benjamin’s attempt to capture the psychology of modern life through an examination of the transitional space of the arcades, Debord saw the construction of situations within the streets as being ephemeral acts that function as transformational ‘passageways’ out of the crisis of modern culture through a form critical play – the notion adapted from Johan Huizinga’s conception of play in his text Homo Ludens.[39] Yet, as Jan Bryant notes, the SI located ‘play in unyielding opposition to boredom, resisting the more measured pace of someone like Walter Benjamin.’[40] Through the concrete construction of situations, the SI attempted to transform the banal or boring into the ‘superior passional quality’ of a new urbanism freed from the domination of the commodity spectacle.[41] One of their primary means of attempting this transformation was through the practice of psychogeography.

For the SI, psychogeography functioned as a major strategy in the resistance of commodity culture and the spectacle because it actively disrupted the experience of the city through a physical and psychological reconstitution of space. Rather than being organized on a principle of commerce, psychogeography responds to the random and often bored wanderings or driftings of separated pedestrians within urban space, whose divergent emotions and behaviors serve to ‘neutralize each other and maintain their solid environment of boredom.’[42] Using these conditions, psychogeographical research aimed at undermining this environment of boredom through the production of a model for imagining and mapping a new or unitary urbanism. As defined by the SI, unitary urbanism is the ‘theory of the combined use of the arts and techniques as means contributing to the construction of a unified milieu in dynamic relation with experiments in behavior.’[43] As such, unitary urbanism functions as the end goal of psychogeography as a practice, in which psychogeographical research is applied to the production of a non-alienated urban environment – alienation being one the characterizing features of urbanism within capitalist culture. Psychogeographical attempts to unify the urban space of the city were aimed at making visible and thereby undermining the alienating effects of everyday modern life, which served to separate subjects both physically and emotionally from the world in which they lived. The use of psychogeography by the SI therefore must take modern boredom as its corner stone, since it is the ‘experience of boredom’ that ‘renders the limitations of rationalized self-understanding visible: the impossibility of rendering questions of meaning to material calculations, the incommensurability of desire and world.’[44] Psychogeography is an attempt to solve this incommensurability of desire and world by imagining and mapping a new environment constructed through momentary situations, in which the meaninglessness of a social and cultural life based upon material calculations is replaced by the meaning derived from the principles of directed living and play.

It is important to remember that like all SI practices, psychogeographical research requires direct involvement and intervention into the physical and psychological space of the city. The primary technique by which these direct interventions occurred was through drifts or dérives, a basic SI practice that involved the ‘playful constructive behavior and awareness of psychogeographical effects and are thus quite different from classic notions of journey or stroll.’[45] Put simply, the drift or dérive involved one or more individuals wandering through the streets of the city, not lost but with no particular destination in mind. ‘Like the flâneur,’ Sadler notes, the situationist ‘drifter skirted the old quarters of the city in order to experience the flip side of modernization.’[46] And in the tradition of the flâneur, the SI viewed the dérive as an active critique of commodity culture because this journey or stroll was engaged in without the necessity to produce anything through the experience – which is the explicit purpose of tourism and shopping – but instead with the explicit goal of being ‘at play.’ In this manner, the act of the dérive provided a forum for individuals to witness and experience the psychology of the city through a direct exploration of its various spaces and situations.

In addition to the figure of the flâneur, there are two Dada and Surrealist excursions that represent significant cultural precedents for the use of dérive by the SI. The first, organized by André Breton, is the Dada excursion to the abandoned medieval church of Saint-Julien-le-Pauvre in Paris on April 14, 1921. This excursion, which represented a significant departure from the usual Dadaist antics performed on stage or within cultural institutions, relocated Dada to the everyday streets of the city. As the program for the excursion stated: ‘The Dadaists passing through Paris, wishing to remedy the incompetence of suspect guides and cicerones, have decided to organize a series of visits to selected spots, particularly those which really have no reason for existing.’[47] The choice to stage a visit and tour of Saint-Julien-le-Pauvre – a site in a non-commercial and poorly maintained part of Paris – represented an active critique of tourism and the spectacle of commodity culture because, whereas tourism reframes the city into a consumable commodity object, Breton’s excursion attempted to discover the marvelous within the mundane everyday space of an abandoned church. This act of urban dérive, in which people met at the church and were encouraged to wander freely around the area, exposed participants to the flip side of modernization in much the same way the Situationists attempted with their own drifts. The second precedent of the dérive, again organized by Breton, is the surrealist excursion to Blois on May 1, 1924. Less ambitious than the public tour of Saint-Julien-le-Pauvre, this dérive involved a small group of four surrealists – Breton, Louis Aragon, Max Morise, and Roger Vitrac – who caught a train to the town of Blois, which ‘they had picked at random on the map…. Their goal was an absence of goals, an attempt to transpose the chance findings of psychic automatism onto the open road.’[48] The randomness of this particular dérive caused a number of problems for the group, beginning with the fact their chance destination was in the country, eventually causing Breton to end the experiment ten days after they embarked. As Debord notes: ‘An insufficient awareness of the limitations of chance, and of its inevitably reactionary effects, condemned to a dismal failure the famous aimless wandering attempt…by four surrealists, beginning from a town chosen by lot: Wandering in open country is naturally depressing, the interventions of chance are poorer there than anywhere else.’[49] Yet even in its ‘dismal’ failure – which was the fate of the Saint-Julien-le-Pauvre excursion as well – the potential of Breton’s experiment in dérive represented an important avenue for critically addressing the crisis of modern culture that was taken up by the SI.

The similarities between the excursions organized by Breton and the drifts or dérives of the SI are substantial. Aside from the obvious parallels in tactics and processes, both manifestations of the derive at their core represented attempts to position the subject in a direct relationship with the physical and psychological space of modern culture that is not dependent upon consumption or alienation, but instead was based on a form of play. In the SI practice of dérive, Debord states:

In this statement, Debord is adamant to minimize the role of chance, which he articulates as the reason for the failure of the Blois excursion, within the process of the situationist drift – a distinction that also served to differentiate the SI employment of dérive from that of the surrealists. Chance elements or processes within a dérive are seen as an unawareness of the physical and psychological influences of the urban landscape on subjects, influences that are made visible through the continuing practice and research of psychogeography. Rather than functioning as a random, or chance (surreal), encounter with the unknown elements of the city, Debord viewed the dérive or drift as a direct form of study, providing lessons from which the SI could draw in order to draft ‘surveys of the psychogeographical articulation of a modern city.’[51]

Ironically, much like their Surrealist predecessors – who also occupied a terminal phase ‘in the crisis of culture’ – the expected potential of the SI dérives or drifts as a means of formulating a psychogeographic critique of capitalist culture was never fully achieved. As Sadler points out, the theory of the dérive, as well as the situationist maps of Paris, resulted in a psychogeography of ‘organized spontaneity’ that ‘certainly didn’t collect much real data.’[52] In fact, the significance of the SI construction of psychogeography as a means of researching and imagining a utopian urban environment is the result of the process more than the product – Sadler going so far as to proclaim the Situationist’s unprecedented abandonment of such early revolutionary goals as the groups ‘greatest contribution to the history’ of the avant-garde.[53] This methodological abandonment represents a major shift in artistic practices, particularly in relation to the SI interest in studying and engaging with everyday life not as art but as a form of direct intervention; a result of this process is the turn by artists away from modernist objectivities towards subjective experiences and representations of the everyday life within culture – such as, for example, personal engagements with boredom – as a means of redefining the space of the city as a lived environment.

The Methodological Vacuum of Boredom

In large part, this ‘dismal failure’ – to use Debord’s phrasing when describing Surrealism – of psychogeography reflected a number of fundamental flaws in the fabric of the Situationists’ goals. Their expressed aim was the liberation of the space of the city and the modern subject through the formulation of momentary situations or new ambiances,[54] a line of resistance that coincides with the commodity’s most advanced line of attack in the form of the ever-new spectacle – this remained hidden from SI. Similarly, the ‘organized spontaneity’ of psychogeography assumed ‘that we all want the same things from the city, and that our experience and knowledge are homogeneous.’[55] The SI – as well as that of the modernist avant-garde generally – was unable to acknowledge the contradictions inherent in the relationship between capitalist culture and the subject. Part of the problem results from the SI view of the modern subject, who is perceived as being unable to break free of the tyranny of the spectacle – the assumption being that the subject, like the SI, homogeneously desires the same revolutionary urbanism. Boredom is therefore seen as counterrevolutionary because it makes subjects unable to engage critically. Patricia Meyer Sparks points out that the Situationists’ conspiracy theories assumed ‘boredom to be a product of social forces rather than a matter of individual responsibility.’[56] However, if boredom is “partly objective, partly subjective” as Heidegger argues, then the subject must then be seen as participating in her/his own experience of boredom.[57] In this manner, the state of boredom reflects a number of significant aspects of contemporary culture that are based upon the interrelationship between subject and city or culture, such as the staging of multiple histories and perspectives of social engagement – a process most visible in feminist uses of boredom.[58] The failure of the Situationists’ experiments in psychogeography can in this way be seen as a result of their inability to acknowledge the subjective and therefore multiple experiences of urban space and culture – boredom functions as an ideal gauge for examining the interrelationship between individual and social forces.

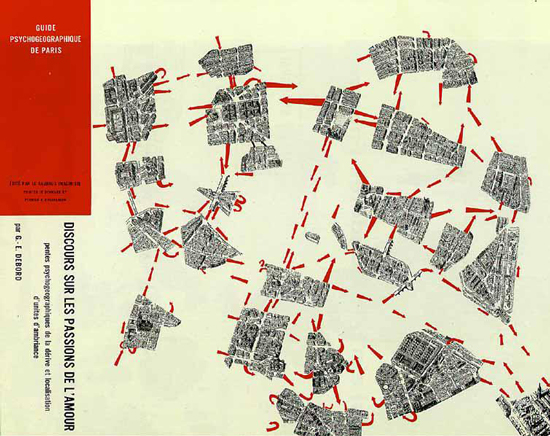

Image 3: Psychogeographical Map of Paris

Image 3: Psychogeographical Map of Paris

At the center of the SI project, Sadler informs us, ‘was a methodological vacuum, a groping for the nonspectacular, some kind of everyday “other”.’[59] As I have argued, the methodological vacuum at the center of the SI project is embodied in the experience of boredom. By making visible the laws and effects of the urban environment and the mediation of the ever-new spectacle on individual subjects, boredom represents an ideal state of psychogeographical research because this state of meaninglessness opens modern subjects up to the possibilities of using their alienation as a catalyst for change. To be bored with the spectacle of capitalism is to possess the potential to challenge the modern crisis of meaning and culture by seeking alternative forms of living that are not mediated by the cycles of commodity culture. As Bryant points out, the SI ‘were blind, not only to boredom's intrinsic potential, but also to its conceptual complexity, seeing it simply as an effect of alienation, something to be defeated.’[60] Rather than something to be defeated by the ever-new play-activities of the SI, boredom can be seen as a form of resistance intrinsic to the everyday interactions of urban life and to the city as a site intimately connected with modern commodity culture and entertainment. Boredom is in itself patently counterrevolutionary because it typically leads subjects back into the grip or fold of the spectacle. But, like the spaces or gaps separating the fragmented elements within the psychogeographical maps in the pages of Mémoires or the famous Naked City, the conceptual space left by the nonspectacularity of boredom provides the subject with the potential for confronting the crisis of culture.

[1] Anonymous. ‘The Bad Days Will End’, from Internationale situationiste, no. 7 (1962), in Knabb, Ken (ed.). Situationst International Anthology (Berkeley: Bureau of Public Secrets, 2006), 112.

[2] This statement is taken from Raoul Vaneigem’s opening sentence in A Cavalier History of Surrealism, except for the replacement of “Surrealism” with “Situationism.” Vaneigem, Raoul. A Cavalier History of Surrealism, trans. Donald Nicholson-Smith (Edinburgh: AK Press, 1999), 3.

[3] Debord, Guy. ‘Report on the Construction of Situations’, in Knabb, Ken (ed.). Situationst International Anthology (Berkeley: Bureau of Public Secrets, 2006), 32.

[4] Ibid., 39.

[5] Although the figure of the flâneur has typically been regarded as male, there have been a number of texts discussing the relationship between women and flâneurie. See Gleber, Anke. ‘Women on the Screen and Streets of Modernity: In Search of the Female Flâneur,’ in The Image in Dispute: Art Cinema in the Age of Photography, ed. Dudley Andrew (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1997).

[6] Benjamin, Walter. The Arcades Project, trans. Howard Eiland and Kevin McLaughlin (Cambridge: Belknap Press, 1999), 22.

[7] Ibid., 10.

[8] Debord, Guy. The Society of the Spectacle, trans. Donald Nicholson-Smith (New York: Zone Books, 1995), 12.

[9] Ibid., 12.

[10] Ibid., 16.

[11] Debord, Guy. ‘Introduction to a Critique of Urban Geography’, in Knabb, Ken (ed.). Situationst International Anthology (Berkeley: Bureau of Public Secrets, 2006), 8.

[12] Sadler, Simon. The Situationist City (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1999), 69.

[13] Anonymous. ‘Détournement as Negative and Prelude’, from Internationale situationiste, no. 2 (1958), in Knabb, Ken (ed.). Situationst International Anthology (Berkeley: Bureau of Public Secrets, 2006), 67. This technique, which most notably is traced back to the nineteenth century author Lautréamont, has been employed by virtually every avant-garde movement or collective and was a fundamental practice of the surrealists.

[14] Anthony Vidler draws attention to Debord’s use of the 1946 Géographie generale by Albert Demangeon and André Meynier as a significant source of material for the Mémoires collages; in addition, Vidler notes that this textbook ‘also set out what will become the foundations of a developed, dérive-driven psychogeography: first in its explication of the forms and functions of cartography, and second in its consideration of cities, always, of course, in the mode of détournement.’ Vidler, Anthony. ‘Terres Inconnues: Cartographies of a Landscape to Be Invented,’ October 115 (Winter 2006): 17.

[15] Debord, The Society of the Spectacle, 146.

[16] Goodstein, Elizabeth. Experience without Qualities: Boredom and Modernity (Stanford: Stanford UP, 2005), 5.

[17] Svendsen, Lars. A Philosophy of Boredom (London: Reaktion Books, 2005), 22.

[18] Debord, The Society of the Spectacle, 38.

[19] Goodstein, 174.

[20] Schopenhauer, Arthur. The World as Will and Presentation, Vol. 1, trans. Richard E. Aquila (New York: Pearson Longman, 2008), 366.

[21] Ibid., 209.

[22] Kierkegaard, Søren. Either/Or: A Fragment of Life, trans. Alastair Hannay (New York: Penguin Books, 2004), 227.

[23] Ibid., 230-231.

[24] Heidegger, Martin. The Fundamental Concepts of Metaphysics: World, Finitude, Solitude, trans. William McNeill and Nicholas Walker (Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1995), 84.

[25] Jameson, Fredric. Postmodernism: or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (Durham: Duke Press, 2005), 71-72.

[26] Barbalet, J.M. ‘Boredom and Social Meaning.’ British Journal of Sociology 50, 4 (December 1999): 633.

[27] Benjamin, 105-106.

[28] Moran, Joe. ‘Benjamin and Boredom,’ Critical Quarterly 45, 1-2 (July 2003): 170.

[29] Kierkegaard, 227.

[30] Moran, 171.

[31] Debord, The Society of the Spectacle, 21-22.

[32] Goodstein, 416.

[33] Svendsen, 142.

[34] Chtcheglov, Ivan. ‘Formulary for a New Urbanism’, in Knabb, Ken (ed.). Situationst International Anthology (Berkeley: Bureau of Public Secrets, 2006), 1.

[35] It is important to note that the SI is the final manifestation in a genealogy of radical artistic or anti-artistic collectives that formed following World War II, which included the Lettrist Group, COBRA, Lettrist International, and the International Movement for the Imaginist Bauhaus. Key members of the Situationists were part of these previous groups, the conceptual parameters of which can be seen as the foundation of the SI.

[36] Merrifield, Andy. Guy Debord (London: Reaktion Books, 2005), 24-25.

[37] Debord, ‘Report on the Construction of Situations,’ 38.

[38] Ibid., 38.

[39] ‘In play there is something “at play” which transcends the immediate needs of life and imparts meaning to the action,’ Huizinga states. Huizinga, Johan. Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play Element in Culture (Boston: The Beacon Press, 1962), 1. This text is important for the SI because, as Huizinga makes clear, to play is not to consume, not to be productive in the modern sense of the term and therefore is a form of meaning outside and against the society of the spectacle.

[40] Bryant, Jan. ‘Play and Transformation (Constant Nieuwenhuys and the Situationists),’ Drain 4 (Play): <http://www.drainmag.com>.

[41] As Michael Gardiner notes in Critiques of Everyday Life, the ‘Situationists found considerable succour in the seemingly “trivial” acts of revolt and contestation found within the daily life of urban capitalism,’ which they interpreted ‘as latently revolutionary, as signs of a liberated consciousness and the collective refusal to accept passively the boredom and stultification induced by consumer capitalism.’ Gardiner, Michael. Critiques of Everyday Life (New York: Routledge, 2005), 120.

[42] Anonymous. ‘Preliminary Problems in Constructing a Situation’, from Internationale situationiste, no. 1 (1958), in Knabb, Ken (ed.). Situationst International Anthology (Berkeley: Bureau of Public Secrets, 2006), 51.

[43] Anonymous. ‘Definitions’, from Internationale situationiste, no. 1 (1958), in Knabb, Ken (ed.). Situationst International Anthology (Berkeley: Bureau of Public Secrets, 2006), 52.

[44] Goodstein, 24.

[45] Debord, Guy. ‘Theory of the Dérive’, from Internationale situationiste, no. 2 (1958), in Knabb, Ken (ed.). Situationst International Anthology (Berkeley: Bureau of Public Secrets, 2006), 62.

[46] Sadler, 56.

[47] Quoted in Ribemont-Dessaignes, Georges. “History of Dada,” Dada Painters and Poets: An Anthology (second edition), ed. Robert Motherwell (Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard UP, 1981), 115.

[48] Polizzotti, Mark. Revolution of the Mind: The Life of André Breton (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1995), 201.

[49] Debord, ‘Theory of the Dérive,’ 63.

[50] Ibid., 62.

[51] Ibid., 66.

[52] Sadler, 78.

[53] Ibid., 161.

[54] As Debord states: “In contrast to the aesthetic modes that strive to fix and eternalize some emotion, the Situationist attitude consists in going with the flow of time. In doing so, in pushing ever further the game of creating new, emotionally provocative situations, the Situationists are gambling that change will usually be for the better.’ Debord, ‘Report on the Construction of Situations,’ 42.

[55] Sadler, 160.

[56] Sparks, Patricia Meyer. Boredom: The Literary History of a State of Mind (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1996), 251.

[57] Heidegger, 88.

[58] An example can be seen in Patrice Petro’ chapter ‘Historical Ennui, Feminist Boredom,’ in which she states: ‘For women modernists, aesthetic and phenomenological boredom provided a homeopathic cure for the banality of the present – a restless self-consciousness (a “desire to desire”) very different from the ideal of disinterestedness that characterizes traditional historiography.’ Petro, Patrice. Aftershocks of the New: Feminism and Film History (New Brunswick: Rutgers UP, 2002), 93.

[59] Sadler, 159.

[60] Bryant.

Julian Jason Haladyn is a doctoral student at The University of Western Ontario (London, Canada), where he presently teaches a course in Visual Arts. He has contributed to such publications as The Burlington Magazine, Entertext, Parachute, C Magazine, On Site Review, and the International Journal of Baudrillard Studies; he also wrote, with Miriam Jordan, a chapter in Stanley Kubrick: Essays on His Films and Legacy (McFarland and Company 2007).

©2008 Drain magazine, www.drainmag.com, all rights reserved