Responsibility to

Adelheid Mers

Part 1: PowerPoint

At a recent conference, I was asked to share examples of how I engage various types of communities through my work. I presented using the customary PowerPoint, and talked about it along the conventions of an artist talk; sketching an intent for each project, outlining processes of research and creation, and showing resulting drawings and prints along with partial interpretations and remarks about the work’s reception. This linear presentation format works well if objects are to be portrayed as the outcomes of art practice (Benjamin’s gallant boudoir), but less suitable to visualize process and complex relations, if that is what is of interest (the messy scene).

Now I have a dilemma: the maps and diagrams I make are premised on the understanding that simultaneity - showing many objects and relations at once – allows for awareness of constitutions (complex figures that include simple figures and the relations among them, to make up powerful grounds), as opposed to focusing on constituents (powerful, simple figures singled out from grounds). How do I re-present my work in a way that matches the process that led to its material results? Can I re-embed that result in process and thus extend it? As much as I intend for my artist talks to evoke grounds, their linear nature undermines that intent and PowerPoints to figures. Oh holy McLuhan, help me!

Part 2: The Chinese Maps

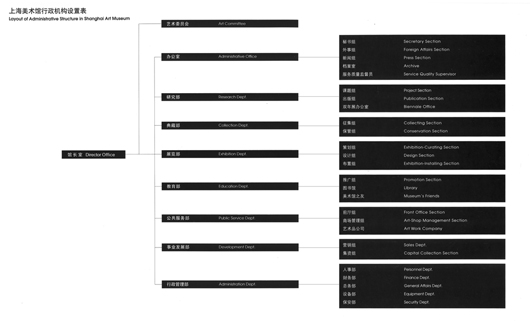

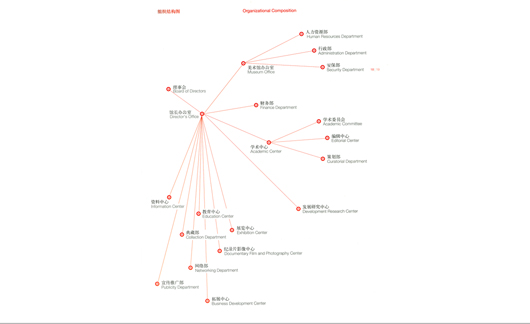

In January 2008, I brought back two maps from a study trip to China: “Organizational Composition” of the Today Art Museum in Beijing and “Layout of Administrative Structure of Shanghai Art Museum”. In fact, I don’t know why these maps were published and I did not have or seek the opportunity to ask, but found it particularly interesting that they evidently are not only for internal consumption, but are presented in booklets to the public. I have not seen maps like those at US museums, where one is likely to encounter columns of individual funders’ names on the entry wall. The Shanghai map presents hierarchies, the one from Beijing a more fluid layout of relations. It is possible to interpret these Chinese maps as reminders of accountability, as tools for transparency or avoidance, or as invitations to participate. Not knowing the conventions that these maps are part of, it becomes exceedingly clear that maps, seemingly complete as they are, need to be grounded as well. But first, these maps inspired me to further think about responsibilities individuals have, take on or are given towards the institutions they participate in.

Part 3: Responsibility

A survey of Western dictionary and encyclopedia entries on responsibility shows that definitions of individual accountability are given primacy, while the notion of ‘responsibility to’ is not only coming second, but is still framed around individual culpability, as the entry in Merriam-Webster’s on-line dictionary exemplifies:

Responsibility:

1: the quality or state of being responsible: as

a: moral, legal, or mental accountability

b: reliability, trustworthiness

2: something for which one is responsible: burden <has neglected his responsibilities> (Merriam-Webster)

In addition, searches for compound forms led to this entry:

‘The notion of collective responsibility, like that of personal responsibility and shared responsibility, refers to both the causal responsibility of moral agents for harm in the world and the blameworthiness that we ascribe to them for having caused such harm.’ (italics original, Stanford)

How can responsibility be framed differently, not as an individual burden, but as a mode to be embraced - as an opportunity for communal participation?

In Why Deliberative Democracy? Amy Gutmann and Dennis Thompson spell out that ‘[r]eciprocity holds that citizens owe one another justifications for the mutually binding laws and public policies they collectively enact.’ (Why 98) Citizenship can be construed as rooted in part in what we owe to each other, particularly as strangers. Responsibility towards others creates readiness to enter into formal community.

In his book Alterity Politics, Jeffrey Nealon holds that ‘[b]oth Bakhtin and Levinas insist that ethics exists in an open and ongoing obligation to respond to the other, rather than a static march toward some philosophical end or conclusion.’ (Alterity 36) Dialogic ethics is an ethics of answerability, of responsibility. It is action owed to others that simultaneously establishes versions of self by ‘expos[ure] to the network of serial substitutions out of which the I emerges.’ (Alterity 51) Responsibility towards others creates the capacity for ethical community.

Nealon continues that “[p]erhaps what we require is not an identity politics of who we are, but an alterity politics of how we’ve come to be who we are: not the answerability of Bakhtinian subjective privilege, but the Levinasian responsibility engendered by the other.” [Alterity 51, author’s italics] Responsibility towards others creates ties in community.

Levinas is shown by Nealon to see face-to-face encounters with specific others - the moments in which self is enacted - as the basis for solidarity. We owe to each other because we are mutually constitutive. Thus, “it is outside the self that we need to look for the conditions of agency, responsibility, and ethical subjectivity.” (Alterity 51)

A focus on what is outside the self is concerned with response, expressed in a more exulted manner by Vilém Flusser: “the celebratory leisure of the Judeo-Christian tradition is ‘responsibility’ (response to calls).” (Writings 167) In the essay “Celebrating”, Flusser describes how revelatory Judeo-Christian traditions can join with Greek academic traditions of discovery to achieve a state of “dialogic programming” (Writings 170) that is “approximately what Buber called “dialogic life”.” (Writings 169) Response to others creates conditions for a community of play.

In the face of globalization and newly arising needs for solidarity, philosopher Karl-Otto Apel seeks “a communicative rationality of grounding” through transcendental-pragmatic discourse ethics that are based in a “situation of arguing” (Discourse 507). Response to others creates ways to establish a community’s rules.

Each in different ways, Gutmann and Thompson, Nealon, Bakhtin, Levinas, Flusser, Buber and Apel explore constituting grounds of mutuality. This ground appears to be related to auditory space, not to vision, but to hearing, speaking, listening.

Part 4: Thank you!

“Acoustic Space is a projection of the right hemisphere of the human brain, a mental posture which abhors priority-making and labels and emphasizes the pattern-like qualities of qualitative thinking. McLuhan pointed out repeatedly that the passion of the visual space mind-set leaves little room for alternatives or participation. […] Acoustic space is built on holism, the idea that there is no cardinal center, just many centers floating in a cosmic system, which honors only diversity. The acoustic mode rejects hierarchy; but, should hierarchy exist, knows intuitively that hierarchy is exceedingly transitory.” (The Global ix) Flusser’s responsibility as response to a calling meets McLuhan’s understanding that “the meaning of meaning was relationship.” (The Global xi).

The visual space of PowerPoint decidedly does not support the acoustic mode. Do large-scale visual maps/diagrams mimic acoustic space? What McLuhan presents me with, in response to my plea above is another, inherently formal connection between maps/diagrams and the question of responsibility. He also points to a new way of re-presenting my work.

Part 5: Re-presentations

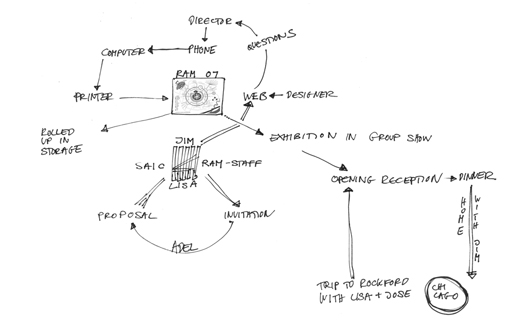

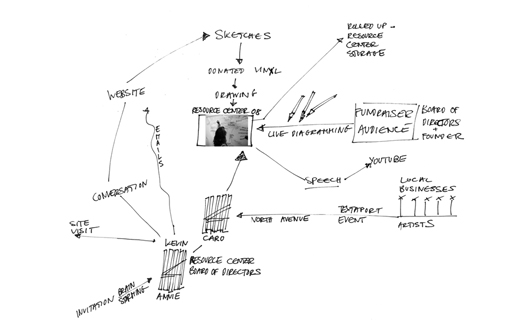

1: Re-presenting the “Rockford Art Museum Organogram 2007”

Re-presenting the “Resource Center Organogram 2008”

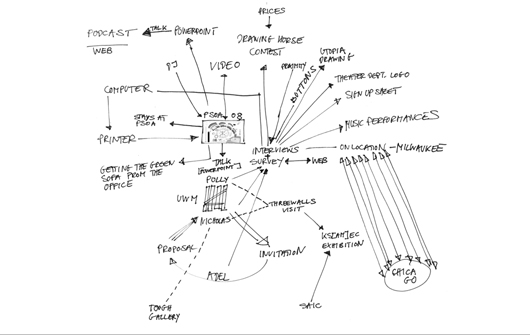

Re-presenting the “Peck School of the Arts Organogram 2008”:

Works cited:

Apel, Karl-Otto; Discourse Ethics as a Response to the Novel Challenges of Today's Reality to Coresponsibility. The Journal of Religion, Vol. 73, No. 4, (Oct., 1993), pp. 496-513. Published by: The University of Chicago Press

Flusser, Vilém; Writings. University of Minnesota Press. 2002

Gutmann, Amy and Thompson, Dennis; “Why Deliberative Democracy?”, Princeton University Press, Princeton and Oxford, 2004

McLuhan, Marshall and Powers, Bruce; The Global Village. Oxford University Press. 1989

Nealon, Jeffrey; “Alterity Politics - Ethics and Performative Subjectivity”, Duke University Press, Durham and London,1998

Websites:

http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/responsibility, 4/30/2008

http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/collective-responsibility/, 4/30/2008

Adelheid Mers is a visual artist who lives and works in Chicago. She diagrams texts and contexts, making site-specific diagrams of art institutions (organograms), lectures and studio visits. She is Associate Professor in the Arts Administration and Policy Program of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. She has served on the editorial board of WhiteWalls since 1995 and edited the issue Useful Pictures, published in 2009, which is available from the University of Chicago Press. adelheidmers.org

©2009 Drain magazine, www.drainmag.com, all rights reserved